Population Growth and Public Image

From 1890 to 1920, the City of Rio de Janeiro experienced rapid growth, with the population of the federal district more than doubling in these years, from 500,000 to over 1,000,000. This expansion resulted from the influx of both former slaves from the countryside and Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian immigrants from outside of the country. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the population of Rio’s downtown comprised a heterogeneous collection of diverse classes, ethnicities, and social groups. This diversity in this part of the city would not last, however, due to sweeping efforts to modernize the city during the administration of President Rodrigues Alves from 1902 to 1906. As his efforts largely became realized, new construction disrupted an enormous segment of the population. Over 20,000 impoverished and largely Afro-Brazilian individuals were displaced from their homes?typically cramped communal quarters known as cortiços or estalagens?over this four-year period.

These displaced and discontented Cariocas expressed their displeasure at these efforts for five violent days in November, 1904, in an event known as the Revolta Contra Vacina?the Vaccine Revolts.

In 1902, Rodrigues Alves embarked on an Europeanization campaign under the rallying call “Rio civilizes itself.” The campaign had two major components: a major public health effort and an architectural facelift in the vein of Parisian city planner Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann. Francisco Pereira Passos, as mayor of Rio, set out to raise the city’s international profile and attract foreign capital by providing familiar images of architectural spaces to international elites, thereby establishing Brazil’s relevance to the European economic order. Passos also exercised a good deal of social control; the mayor banned beggars from city streets, outlawed cows and other livestock, and forbade spitting in public. During these efforts, Rodrigues Alves wrote hopefully of Rio’s future:

Its restoration, in the eyes of the world, will be the start of a new life, the beginning of work in the far-reaching areas of a country which has land for all cultures, climates for all peoples, investment potential for all sorts of capital (Underwood, 55).

Brazil, it seemed, had room for “all peoples,” but not all of its own population.

The Beginning of the Vaccination Campaign

Rodrigues Alves and Passos believed that, alongside insufficient architectural grandeur, disease was ruining Rio’s image abroad. Disease became associated with a firm belief in the inferiority of Rio’s urban poor, such that Inspector of Public Health Agostinho Jose de Souza Lima reported in 1891 that the city promoted a “complete absence of moral virtue” among its inhabitants, who were living a life of “horrendous nudity and licentious behavior.”

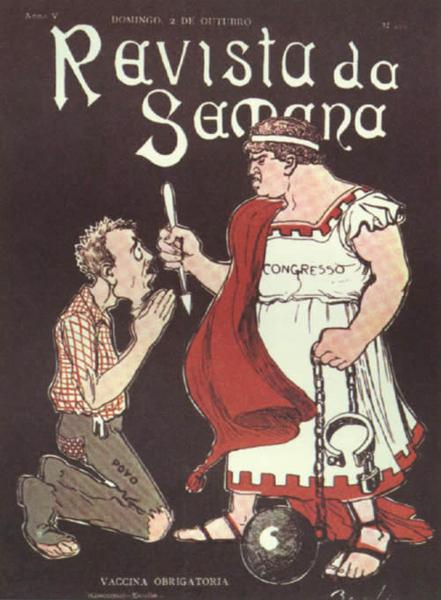

To remedy this situation, Rodrigues Alves appointed Dr. Oswaldo Cruz as the Director of Public Health. In this post, Cruz ordered the drainage of all pools of stagnant water in downtown Rio, the spraying of mosquito larvae, and the demolition of all “unsanitary” housing. Cruz, a devoted follower of the innovative French microbiologist Louis Pasteur, employed new discoveries in medical and biological research and ordered new sanitary brigades to inspect, clean, repair, and sometimes demolish houses deemed to be unhygienic. These efforts were successful in reducing the incidence of yellow fever and the plague by 1903, but they inspired sporadic popular resistance. Fatefully, when Cruz called for the government to pass legislation mandating the obligatory vaccination of Rio’s residents against the smallpox virus,

this resistance crystallized into organized opposition.

Rising Opposition

On November 11, the day the vaccination law was to take effect, an unlikely but powerful alliance formed to oppose the program. The coalition included union and non-union laborers, students, the city’s marginalized poor, radicals, journalists and junior cadets from the Military Academy. They organized themselves into an ad hoc group called the Liga Contra Vacina Obrigatória. For five days a series of protests escalated into a riot that engulfed the city and destroyed many of its recent improvements.

The revolt did not result merely from a fear of medical treatment, but rather an ideological opposition to the obligatory aspect of the inoculation program; the Revolta Contra Vacina was for many of its combatants a fight of the poor against state interference in their private lives. The popular reaction against the campaign was due to the prevalence of popular values incompatible with government programs in this era, particularly standards of family morality. Visits by doctors in the possible absence of the head of the household, as well as the possibility of a stranger physically interacting with wives and daughters, posed a violation of a husband’s sense of honor and a serious intrusion into the domestic sphere. In the early twentieth century, there still existed a traditional notion of the relationship between citizen and government that included governmental non-involvement in ordinary lives. The attempts at modernization in fin de siècle Rio de Janeiro challenged this relationship, and Cruz’s compulsory public health measure catalyzed the most dramatic public resistance to this change as a result.

Although the rioters were angry and belligerent over the violation of the home proposed by the new government policy, the violence that ensued was not the complete anarchy typically reported. Instead it was part of a coordinated strategy of the Liga to distract and divide police forces in order to facilitate a military coup d’état being organized by Lauro Sodré?a leading Positivist Senator to the Federal Congress from the State of Pará. On November 15 (the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Old Republic), a group of Positivist cadets launched the abortive attempt to overthrow the government, using the street violence to discredit the government in power and create an environment favorable to revolution.

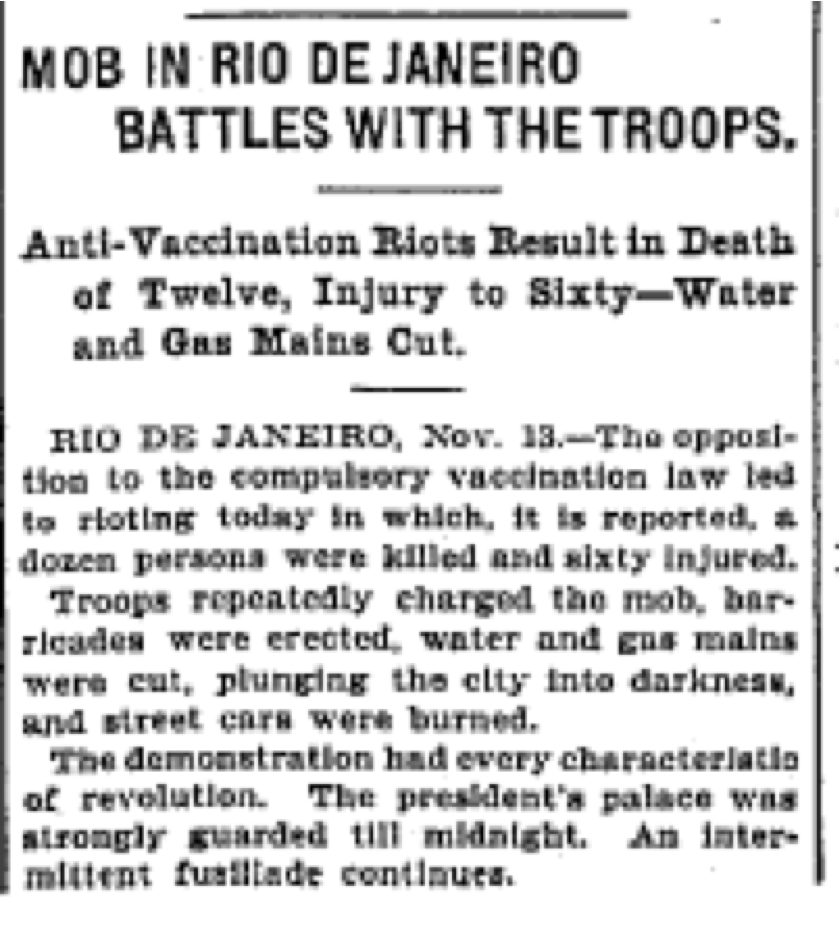

Although the coup failed, the rioting was destructive. Rioters burned streetcars and cut water and gas mains, depriving the city of its basic utilities. A dozen rioters were killed and over 60 were injured in the first three days of the insurrection. By the morning of November 16, all municipal transportation from downtown Rio to outlying areas had come to a halt, due to repeated attacks on cars and drivers. The next day the government announced its plan to repeal the mandatory vaccination against smallpox, which quickly deflated unrest and restored order in the city.

Despite repeal of the universal vaccination law, the government continued with its public health and modernization campaigns, including the destruction of swaths of unsanitary tenements in the downtown area. With affordable options for housing eliminated and without any plans for more to be built, the poor that remained moved in droves to makeshift favelas and to the company-controlled towns encircling factories in the outskirts of the city.

The Aftermath of the Revolt: The Rising Tide of Modernization

Ultimately, the Vaccine Revolts only accelerated the modernization of Rio. Rodrigues Alves discredited the protesters as barbarians, ignored their concerns, and deported many of them to the sparsely-populated territory of Acre. These deportations were just one more addition to the overall “civilization” of Rio’s urban renewal project. Notably, in 1909, a similar program for vaccination met with no such resistance as was seen in 1904. By this point, vaccination was no longer intimately connected with urban renewal programs and the working poor had already been relocated from downtown Rio.

Although popular opposition centered on the obligatory vaccine law, the Vaccine Revolts were in fact the result of a broad range of grievances related to the city’s rapid growth, including concerns over food shortages, inadequate city services, unemployment, and Rodrigues Alves’s broad urban modernization campaign, as well as the chronic inflation that had been decreasing the average standard of living for over a decade. The president’s attempt to position Brazil among the ranks of modern, Western nations revealed the difficulties with rapid modernization. Ironically, this brief outburst of public sentiment comprised a diminishing cadre of Positivists in the military who, despite their faith in progress, still subscribed to a worldview that disregarded the equality of the marginalized poor. In a sense, the rioters used the Vaccine Revolts to express their objections to the Positivists’ stated goals: order and progress and a modernized Brazil.

Further Reading

- For a comparison with similar urban renewal projects in another area, Lúcio Kovarick’s Social Struggles and the City: The Case of São Paulo is a study of modernizing attempts in the same period in São Paulo.

- Janice E. Perlman’s The Myth of Marginality: Urban Poverty and Politics in Rio de Janeiro studies the continued impact of urban poverty on the city.

Sources

- Adamo, Sam. “The Sick and the Dead: Epidemic and Contagious Disease in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil,” in Cities of Hope: People, Protests, and Progress in Urbanizing Latin America, ed. Pineo and James A. Baer. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1998.

- Meade, Theresa. “Living Worse and Costing More: Resistance and Riot in Rio de Janeiro, 1890?1917.” Journal of Latin American Studies, Vol. 21, No. 2 (May, 1989), 243.

- ” ‘Civilizing Rio de Janeiro’: The Public Health Campaign and the Riot of 1904.” Journal of Social History, Vol. 20, No. 2 (Winter, 1986).

- “Mob in Rio de Janeiro Battles With the Troops.” Chicago Daily Tribune. 14 November, 1904.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. “The Revolta Contra Vacina of 1904.” Riots in the Cities: Popular Politics and the Urban Poor in Latin America, 1765?1910, ed. Silvia M. Arrom and Servando Ortoll. New York: Scholarly Resources Printing, 1996.