The Handmaiden of Art: British Portrait Engraving, 1760-1820

Elizabeth Perry

The Eighteenth century in Britain was the golden age of both formal portraiture in the "grand manner" and the portrait mezzotint. Prints of formal military portraits in this period were usually mezzotints made after paintings by Reynolds and his school. In these works, as in the vast majority of prints of the time, the reproductive engraver copied the original creations of other artists. At the same time, however, the engraver created a new, unique art object. It has been estimated that eighteenth. century British reproductive prints outnumbered original prints by at least fifty to one. Debate about reproductive prints has focused historically on their status as "original" fine art, a concept itself defined in respect to reproductive art. This debate was particularly heated in the eighteenth century when painters and art critics assigned printmaking the rank of handmaiden or nurse to the superior arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture. The debate over the status of the print as fine art has long since been resolved in favor of the engravers, and the highly influential role played by reproductive engraving in eighteenth-century art and society has become apparent to contemporary scholarship.

Portrait engraving in Britain began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries as frontispiece portraits to be bound in books or sold separately. Engraving became established in England a century later than on the Continent, and the earliest engravers in Britain were from the Low Countries. The first important British portrait engraver was William Faithorne (c. 1616-1691), whose line-engraved portraits are characterized by a vigorous, convincing presence. By the close of the seventeenth century, mezzotint engraving was superceding line engraving in popularity, and younger artists such as Faithorne's son, Faithorne II, were abandoning line engraving for the new technique.

Mezzotinting was a form of engraving developed in about 1640 by Ludwig von Siegen (1609-after 1676) of Utrech. A tonal rather than linear process, mezzotints were created from dark to light, resulting in luminous whites emerging from velvety blackness. The engraver first roughened the surface of the copper plate with a rocker, a tool with a curved surface of sharp teeth. This instrument was "rocked" across the plate in all directions until the smooth plate was entirely covered with small burred incisions that held the ink. This time-consuming process required patience rather than expertise and could be carried out by the engraver's assistants, and thus mezzotint required less skilled labor than line engraving, in which the entire plate had to be covered with tiny lines by the engraver's hand. The roughened surface of the prepared mezzotint plate would print as a dense black. With a scraper and a burnisher, the engraver then polished the pitted surface smooth again wherever he wanted lighter areas, the degree of tone being determined by the relative roughness of the plate and the amount of ink it could hold. Frequently, etched or engraved lines were then added to the plate in order to strengthen the image.

The surface of the mezzotint plate wore quickly in printing and could yield only about one to two hundred high-quality prints. Because of this, the mezzotint was not practical for book illustration, and line engraving continued to be used for that purpose. Perhaps because of the greater time and expense involved in line engraving and its association with past masters and prints of illustrious persons, it had higher status than the mezzotint in the hierarchy of print processes. History painting, perceived in the period as the highest form of painting, continued to be almost exclusively reproduced by line engraving.

The tonal nature of the mezzotint technique was quickly recognized as perfectly suited to capturing the chiarosuro effects of oil portraits, and mezzotint became the preferred medium for portraiture outside of the book trade. As in line engraving, the earliest mezzotinters in England were Dutch, but eventually mezzotint engraving became so popular and well developed in England that it became known throughout Europe la maniere anglaise. The fame of portrait painters working in England was spread by the work of the mezzotint engravers George White (c. 1671-1732) and John Simon (1675-1751), and especially by John Smith's (c. 1652-1]42) prints after the works of Sir Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723).

The work of John Faber the Younger (c. 1695-1756), son of a mezzotint engraver from The Hague, spanned the period from Kneller to Sir Joshua Reynolds. Faber's work was uneven, comprising a large number of indifferent mezzotint portraits, and his name is associated with a perceived decline in mezzotint engraving of this period. The art of the mezzotint was, however, alive in Dublin, and Irish engravers working in London were responsible for the revival and full flowering of mezzotint engraving. In 1762 Horace Walpole wrote that the Irish engravers "have already promised by their works to revive the beauty of Mezzotint."l1 The Irish dominated mezzotint engraving for the next twenty years. The Irish line engraver John Brooks (active 1730-1755) visited London in 1740 and learned the technique of mezzotinting there, possibly from Faber. When he returned to Dublin in 1741, he acquired several pupils and, with his assistant Andrew Miller, announced plans to produce by subscription a folio of one hundred mezzotint portraits. The ambitious plan was never completed and in 1746 Brooks left Dublin for London, bringing with him his pupils James McArdell (c. 1729-1765) and Richard Houston (c. 1721-1775). Only two years later, in 1748, McArdell and Houston were counted among London's leading mezzotint engravers. They were followed by more Irish engravers, including Edward Fisher and James Watson.

In London, McArdell engraved a variety of fancy pictures, portraits, and other works after van Dyck and Rubens. Reynolds commissioned McArdell in 1754 to engrave his portrait of Lady Charlone Fitzwilliam as a child. It was the only print Reynolds published himself, and he appears to have used the attractive print as an advertisement. A partnership was born, and McArdell engraved nearly forty more mezzotints after Reynolds's work as well as another two hundred after other artists. Reynolds is said to have declared that he would be immortalized by McArdell's prints. After McArdell's early death in 1766 until about 1775, Reynolds turned to other Irish engravers to reproduce his pictures, especially James Watson. Sir Joshua Reynolds was the most widely reproduced artist in eighteenth century Britain; over four hundred prints were made after his paintings during his lifetime by various engravers. He was keenly aware of the importance of prints and employed them frequently as samples and advertisements. Reynolds's pupil and biographer James Northcote (1746-l831) has noted his extensive use of prints as models:

[Reynolds] kept a portfolio in his painting room containing every print that had been taken from his portraits; so that those who came to sit had his collection to look over, and if they fixed on any particular attitude, in preference, he would repeat it precisely in point of drapery and position; as this much facilitated the business, and was sure to please the sitter's fancy.

Reynolds was careful to allow only those engravers in whom he had confidence the privilege of reproducing his work. In criticizing the work of the engraver Edward Fisher, Reynolds acknowledged the essentially interpretive nature of the reproductive print: Fisher's work, Reynolds said, was "injudiciously exact" and he wasted time "making every leaf on a tree with as much care as he would bestow on the features of a portrait.

The relationship between painting and the print was intimate, but it was impossible for a reproductive print to be a perfect replica of a painting, since the physical media-oil color on canvas versus monochromatic ink on paper-were completely different. Reproductive prints could and often did distort the intention of the painter. Engravers sometimes sweetened images, idealizing them and making them more picturesque.

The influence between painting and engraving was reciprocal: painting influenced printmaking, and prints influenced paintings. Some paintings, such as those commissioned by the printseller John Boydell for his Shakespeare Gallery, were specifically designed to be reproduced. Indeed, it has been suggested that Reynolds's painting style was influenced by the mezzotint in its preoccupation with chiaroscuro effects.

During the eighteenth century, mezzotint engraving moved from a state of decline into its golden age. The essayist William Gilpin hardly exaggerated when he stated in 1768 that "Mezzotinto, compared with its original state, is, at this day, almost a new art." By 1775, the Irish engravers began to fade from activity, into death or retirement. But beginning in the 1760s, a new school of English engravers had begun to build on the accomplishments of the Irish, and they became dominant in the last quarter of the century.

John Raphael Smith (1752-1812) was the foremost engraver of the new English school. Although the son of an artist, Smith received no formal art training and was apprenticed at the age of ten to a linen draper. His first published print, a mezzotint published in 1769, was of a military hero, the Corsican patriot Pascal Paoli. For several years he freelanced as an engraver, and then opened shop as a linen draper, selling fabric and ladies' trimmings such as gold and silver lace. During the 1770s "subject pieces," prints after historical and literary subjects, became increasingly popular. Sensitive to the changing demands of the market and working in a variety of techniques, Smith took advantage of the vogue for subject and fancy pictures executed in stipple-engraving and made many such prints after his own designs. An astute businessman, Smith became a print publisher and dealer, and ran a manufactory for colored prints, employing the young J.M.W. Turner as a colorist, and exporting the colored prints to France in exchange for wine and other merchandise. Impossible to categorize, John Raphael Smith was an engraver, a major print publisher and dealer, a portraitist in oil, pastel, and miniature, a linen draper, merchant, and importer.

Although the golden age of the portrait mezzotint was approximately 1760-1780, portrait mezzotints continued to be popular into the 1820s and 1830s. Engravers such as Samuel Cousins (1801-1887) continued 10 reproduce the work of Reynolds as well as scrape mezzotints after the work of contemporary painters, especially Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830).

Prominent engravers were sought after by private clients, painters and dealers. After Samuel Cousins declined to engrave a portrait of Napoleon III and the Empress Eugenie, the Emperor personally requested the work, offering to pay him any price. But this was clearly an exceptional circumstance. The vast majority of engravers toiled for their living in an ambiguous position, caught between the painters and the print dealers.

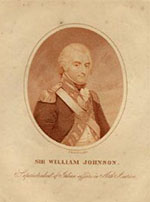

The production of a portrait mezzotint required the efforts of many skilled people. The copyist, who was sometimes also the engraver, made a reduced painting or drawing of a large work. The engraver or his assistants prepared the mezzotint plate and transferred the image to it, usually in reverse so that the printed image would face the correct way. Only then did the actual engraving take place, the engraver burnishing the portrait with his tools. An engraver trained in calligraphy added the lettering and a professional printer and his assistants inked and printed the plates. It is estimated that one line engraving on copper took at least three years to complete in the eighteenth century although mezzotint and stipple required less time.

Training in engraving was by apprenticeship. The close relationship between the master engraver and his pupils is a partial explanation for the success of small interrelated groups of engravers, such as the Irish engravers. Plenty of unskilled work was involved in preparing the plates, and the engraver's workshop was usually a family affair, employing children and in-laws. In addition to informal work for the family business, the wives and daughters of these engraving families frequently worked professionally as engravers in eighteenth-century England. Caroline Watson (c. 1761-1814), daughter of the Irish mezzotinter James Watson (c. 1739-1790), engraved at least 153 portraits, chiefly in stipple, in addition to prints of other subjects, and was appointed engraver to Queen Charlotte.

When the Royal Academy was founded in 1768, engravers were excluded from full membership (only six Associate Engravers were allowed admission) and prints were not exhibited, a snub the engravers bitterly resented, The Academy's opinion was that engraving was a craft and not an art. The line-engraver Sir Robert Strange (1721-1792) expressed his outrage over this exclusion in An Enquiry into the Rise and Establishment of the Royal Academy of Arts (1775), calling the academy's position "an attack upon the art of engraving: a profession which will transmit to posterity the works of painters, when devouring time has left no traces of their pencils." And, referring to Reynolds's fugitive pigments: "I know no painter, the remembrance of whose works will depend more on the art of engraving than that of Sir Joshua Reynolds."

Three inconsistencies in the Academy's position were particularly annoying 10 the engravers. First, Francesco Bartolozzi (1728-1815), the Italian stipple-engraver, was granted full membership, supposedly on the basis of his work as a painter. Second, no other academy in Europe excluded engravers, and lastly, other classes of craftsmen were granted admission, including painters of miniatures and even coach painters.

The engraver John Landseer (1769-1852) became an Associate Member of the Royal Academy in 1806 with the goal of influencing the Academy from within. He then delivered a scathing series of lectures at the Royal Institute in support of the art of engraving. Claiming engraving was a form of incised sculpture, Landseer appealed to the members' faith in the ennobling quality of art and warned of the dire consequences of allowing the art of engraving to drift without instruction and guidance. He threatened the Academy that "If in a given Art, Ignorance shall assume, and attempt to exercise, the superintendence of knowledge, talent in that art will, from that period, begin to decline." Landseer spoke against the print dealers, especially John Boydell, who had become the Lord Mayor of London in 1790, accusing them of exploiting engraving and of encouraging inferior engraving styles:

...to follow, flatter, and degrade, not to lead, exalt, and refine, the Public Taste, is the constant object of these mock MAECENATES of modern engraving — at least in the constant tendency of their profitable endeavours.

For these efforts Landseer received notice that his assistance as a professor at the Royal Institute was no longer required. He published the lectures the following year.

The engravers and their friends considered their art not slavish copying by servile handmaidens but rather interpretive work, the mezzotint employing a language distinct from painting. John Landseer used this analogy in one of his infamous lectures:

Engraving is no more an art of copying Painting, than the English language is an art of copying Greek or Latin. Engraving is a distinct language of Art: and though it may bear such resemblance to Painting in the construction of its grammar, as grammars of languages bear to each other, yet its alphabet and idiom, or mode of expression, are totally different.

An analogy to music was also used to describe the differences between painting and engraving, the painter being compared to the composer of music and the engraver to the performer.

In 1812 fourteen engravers sent a petition to the Royal Academy. In response, the Academy reaffirmed to the King the exclusion of engravers:

That all the Fine Arts have claims to admiration & encouragement, & honourable distinction, it would be superfluous to urge, Your Royal Highness having been pleased to manifest so kind a solicitude for their general welfare, but, that these claims are not all equal has never been denied, & the relative pre-eminence of the Arts has ever been estimated accordingly as they more or less abound in those intellectual qualities of Invention and Composition, which Painting, Sculpture & Architecture so eminently possess, but of which Engraving is wholly devoid; its greatest praise consisting in translating with as little loss as possible the beauties of these original Arts of Design.

In 1826, 1837, and 1853 the engravers appealed again to the Academy, not until 1928 were they finally admitted to the Royal Academy as the equals of their fellow artists. In their final petition to the Academy the engravers had written:

It is our high esteem for the Royal Academy, no less than our anxiety for the honour of Engraving, that moves us to petition you, trusting that the present anomaly will be recognized as meaningless except as the legacy of an unhappy quarre; of long ago.

Engraving was not accepted as a fine art until the technologies of lithography and photography assumed its reproductive functions.

In our age of mechanical reproduction, the unique hand of the reproductive engraver is readily apparent, and in our post-Duchamp art world, the debate over whether reproductive engraving qualifies as fine art is obsolete. As a popularizer and interpreter of art, reproductive art helped shape the artistic sensibilities and taste of the eighteenth century. Beyond these important roles, the excellence of the work of the portrait mezzotint engraver continues to speak in its own unique language.