An Art-Historical Examination of Indo-Persian History

by Alanna M. Benham

The Minassian collection of miniature paintings contains items made by Persians, Turks, and Hindus over at least four centuries. These images represent a great variety of artistic production over vast geographic and cultural territory. As with any art-historical investigation, an understanding of regional history is essential in placing these images within an appropriate context. Of particular importance to the Minassian Collection is the historical exchange between Persia and India. The following is a brief historical account intended to elucidate the conditions which led to the creation of this body of paintings.

The Near East has always been an area of tremendous cultural transfer. Situated at the crossroads between China and India, eastern Europe, and the eastern Mediterranean region, Persia has been subject to the influences of mobilized groups from all directions. Each foreign group to pass through Persia has contributed to the historical epic of triumph and defeat which is Persia's history.

After the paced social and technological growth of the Bronze and Iron ages, Persia began a new historical chapter as a global actor when Cyrus the Great founded the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BCE. Between 550 and 330 BCE, the Achaemenid dynasty grew to incorporate all the territory from the Indus river to the Nile. Based in Persia, this dynasty grew into a major political power which rivaled Greece. Zoroastranism, a religion of local origin which focused upon the importance of celestial and terrestrial balance, was the sanctioned religion. The Achaemenid reign ended when Alexander the Great conquered the region in 330 BCE. Alexander became enamored with Persian culture and to creating cultural exchange between the fortified Greek and Persian cultures, though his successors were more concerned with the economic and political benefits of maintaining control of the region. The Selucids succeeded Alexander. Their control lasted only until 248 BCE, at which time they were expelled by the Parthians, a semi nomadic group from northern Persia.

The Parthians were ousted after only twenty years' reign by the Sasanians. As native Persians, the Sasanians took pride in reclaiming their homeland from foreign rule. They established an extremely stable empire, maintaining control of Persia from 224 BCE until 650 CE. Sasanian culture flourished amidst a high degree of political stability and cultural growth. Poetry and science flourished as the empire expanded eastward. China and Greece were engaged in trade with the Sasanians, and artistic patronage bloomed in this time of plenitude. Artistic influences from China and Greece blended with local Persian traditions, which contributed to the artistic vocabulary used in Persia for centuries to come.

The Sasanians were periodically engaged in war with Byzantium. This contributed to a gradual decay of the former dynasty. Arab invaders capitalized upon this weakness as they swept through the region in the seventh century. The Sasanians were defeated by Arabs in 637 CE. Islam spread quickly through the Arab world, through modern Turkey, Iran and Iraq. Regional instability from conflicting tribes gave the Muslims an advantage in spreading their culture throughout the Near East, creating a large sphere of Islamic influence before the end of the seventh century.

Islam was brought to Persia after a dramatic military defeat by a people who were largely nomadic. The Arab invaders had yet to establish their own cultural traditions; the religion itself was newly born, and their pre-Islamic cultures had not included a developed literary or artistic heritage. Islamic culture was highly permeable to aspects of Persian style and artistic tradition in the first centuries of the Islamic period, though Persian art forms were greatly modified by new Islamic values. There was a tendency away from figurative depiction and toward ornament and decoration in Islamic art, though Persian aesthetics continued to provide a cultural standard for the region. Persian culture became inextricably linked with Islam as the Muslim empire expanded eastward and westward. By the end of the first millennium, Islam had become a dominant religion not only in the Near East but through Spain, Turkey, and India.

The Seljuq dynasty was established in 1037, under which a succession of powerful Persian leaders presided over a century of cultural renaissance. This age succeeded in fusing Islam and Persian culture into a nationalistic expression of Persian identity. However, by the end of the twelfth century, the Seljuq dynasty had weakened in a series of assaults along the eastern frontier. The cultural and political fortitude of the previous age had begun a slow decay. Power structures broke down over the next thirty years until the Mongols came flooding into Persia from the east in 1220. The region was quickly gripped by warfare and brutality. Mongol invaders systematically destroyed repositories of local culture, targeting libraries and mosques. Very little Persian art remains from before the thirteenth century; no manuscripts or paintings are known to predate the Mongol invasion. Scholars were eradicated during a time of unprecedented turbulence. More than a century passed before Persians could turn their attention to cultural repair and reengage in their pursuit of scholarship and the arts.

The Mongol influence remained strong in Persia until roughly 1385 BCE. By this time the region had begun the slow healing process necessary after such a decisive break with previous culture. A new leadership was desperately needed in Persia which could restore the collective memory of Persian cultural glory. Some Mongols converted to Islam and became active contributors to rebuilding Persian culture.

The Timurid, a group of Muslim peoples from Central Asia, invaded Persia in 1385 as part of a massive military campaign reaching from Turkey to India. In 1398 Timur's army reached Delhi. He captured the city in a series of brutal raids, bringing the Hindu state under Muslim rule. Islam would persist in India for 500 years after it was imposed by Timur. The Timurid dynasty controlled Persia for over a century. After an initial period of destruction imposed by Timur in his fight for control of Persia, the house of Timur developed into a strong patron of the arts. The Timurid empire succumbed to Persian culture much like the Mongols had done 150 years before. The Timurid controlled Persia until the turn of the sixteenth century. The first age of peace and stability in almost two centuries nurtured artistic development in Persia. The Timurid became enthusiastic patrons of architecture and manuscript illustration. Fortunately, several Timurid manuscripts have survived to the present day, documenting the advanced state of calligraphy, illustration, and illumination in the early fifteenth century.

The Timurid dynasty remained in power for more than a century until it was displaced by the Safavid dynasty, a group of native Persian rulers. The Safavid dynasty marks an extremely important period in Persian history; for the first~time smce the Arab invasion Persia was united under a native Persian dynasty. The Safavids maintained the generous patronage of the arts begun by the previous rulers; Islamic culture continued to flourish and gain in accomplishment. The land was largely peaceful, and Persia experienced a golden age which lasted through the end of the seventeenth century.

One of the most significant Safavid accomplishments in the sixteenth century was Persia's eastward expansion into northern India. Zahirud-din Muhammad Babar, a Persian ruler from the province of Ferghana, initiated the eastward expansion and became the first ruler of the Mughal court. Babar was descended from Timur of the Timurid Dynasty. He assumed leadership of Ferghana when he was only eleven years old. However, the Uzbek, a tribal people, presented a political obstacle to Babar's reign. They forced him to flee to Kabul, leaving his homeland. After trying in vain to recover his native country from Uzbek domination, he tumed his attention eastward. Babar resigned himself to moving eastward and establishing himself in Hindustan once it became to clear that he would not recover his native land. 14 Babar felt a proprietary right to the lands of northern and western India which had been conquered over a century before by Timur. In 1526 Babar defeated Sultan Ibrahim Lodi at Delhi and founded the Mughal Dynasty. Babar died only four years later, in 1530, at the age of forty-seven.

Babar's eldest son Humayun succeeded him to the throne. He had been raised by his father as an appreciative patron of the arts and focused special attention on enlarging the royal manuscript collection. However, Humayun was not a warrior or a strategist. Parthan invaders defeated Humayun's army in 1540, ousting him from India. The next decade was characterized by political instability and territorial skirmishes. Humayun's son Akbar, born in 1542, was actually raised by the Persian emperor Shah Tahmsap's family while Humayun attempted to restore order to his own ruling house. This alliance proved doubly beneficial for Humayun. Growing up in the cosmopolitan Safavid capital, Akbar received the best possible education in the arts and leadership. Akbar's father also had the good fortune to lure Mir Musawwir and Mir Sayyid 'Ali, two of the most accomplished artists in Shah Tahmsap's royal painting studio, back to the Mughal court at Kabul in 1549. These Safavid court artists were instrumental in the development of the Mughal aesthetic.

Akbar assumed power in 1556, quickly establishing himself as a highly capable leader and a strong patron of the arts. He sought peace in his kingdom, instituting a policy of tolerance for all people regardless of religious affiliation. The Hindu population embraced him as a benevolent leader, and his capital at Agra drew scholars from all parts of India and the Muslim world. Akbar's court encouraged artistic excellence and innovation. Artists began signing their work with greater frequency at this time. From studies of these signatures it has been surmised that approximately 80% of the painters in Akbar's imperial studio were Hindu. These artists brought their own artistic traditions and visual vocabulary with them to the Mughal court. Hindu and Jain painting tended to be more brightly colored and less highly-detailed than Safavid painting. The Mughal paintings created in this cosmopolitan atmosphere represent a great synthesis of Persian, European, and Hindi painting styles.

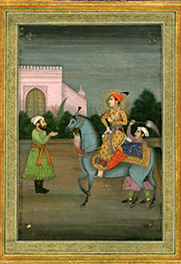

Akbar was an avid supporter of portraiture, commissioning many images of himself and his family at all stages of life. One of the major innovations of Mughal art was the development of a unique genre of portraiture. Never before in Safavid art had the portrait been employed as an independent genre. However, in the early years of the Mughal dynasty, portraiture became one of the most popular types of painting. Although illustrated texts of famous literary works such as the Shahnama remained in demand at this time, there was a new emphasis on commissioning portraits, ornithological studies, and individual paintings to be mounted together in personal albums. This had a profound impact on the future of both Persian and Mughal art.

Akbar's death in 1605 brought control of the extensive Mughal empire to his son Salim. Upon ascending the throne, Salim took the name Jahangir, meaning 'world-seizer.' Jahangir had inherited his father's taste for the arts as well as his empire, and quickly established himself as another great Mughal patron. Jahangir commissioned numerous portraits and natural history studies. He encouraged his the artists in the imperial studio to adopt particular specialties, and reduced the number of artists under his employment. Those artists turned loose by the court were likely in great demand in the many provincial workshops springing up in the larger Indian cities to cater to the patronage of provincial of ficials or to Hindu courts.

Jahangir was succeeded by his son Shah Jahan in 1627. He was not an avid arts patron as his father and grandfather had been, but he had numerous portraits made of himself and his family as befitted an emperor. Shah Jahan reigned without incident for thirty years, raising his four sons in the comfort of the court. However, the end of Shah Jahan's reign introduced a note of turbulence to the Mughal ruling house. He became ill in 1657, and though he recovered, his son Aurangzeb proclaimed himself emperor. He then proceeded to imprison his father and kill his brother Dara Sikoh to avoid contention for the throne.

Mughal influence had been more strongly felt in northern India than in southern India through the sixteenth century. Ahmadnagar, a city due east of Bombay, was claimed by the Mughals in 1600 during the last years of Akbar's reign. However, the Deccani plains of southem India remained under Hindu leadership. Aurangzeb was a Muslim fundamentalist and sought to expand the horizon of the Muslim empire into the Hindu areas of southem India. Aurangzeb had the support of some independent Muslim states in the Deccan and proceeded to acquire political and military control of the region. Bijapur and Golcunda remained under Hindu control until 1686, when Mughal forces permeated the region and defeated the local population. Aurangreb remained emperor until he was 89 years of age, in 1707.

Aurangzeb was not a patron of the arts and the specialized ateliers of the previous generation dispersed shortly after he assumed power. Many of the disenfranchised Mughal artists found work in Hindu courts, which experienced a profusion of growth in the late seventeenth century. Aurangzeb's reign is generally felt to have signaled the end of the great age of Mughal painting.

The Mughal dynasty officially came to an end in 1858 when Queen Victoria of Britain became the Empress of India. By this time, British interests were well established in India. The East India Company had been chartered over 250 years before, in 1600. Since that time, British shipping was firmly entrenched in India, importing luxury items such as tea, precious metals and stones, silk, cotton, and sandalwood. British aristocrats had been installed in India since the early 17th century. Their presence in a foreign land, coupled with the rising prevalence of natural history and scientific investigation made these expatriot Britons eager patrons of Indian artists. The watercolor images of birds in the Minassian collection were likely commissioned by English patrons living abroad in India in the early part of the 19th century. Some of these images are painted on Whatman paper, a British brand. Whatman paper was favored by many European watercolorists in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It was likely brought to India by English diplomats for their personal use or to be used for commissions by local Indian artists.

Meanwhile, artistic patronage continued to thrive through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Safavid Persia. The Safavid Shahs Ismael (1501-1524), Tahmsap (1524-1576), and Abbas I (1589-1627) ruled in times of relative stability and maintained excellent imperial painting schools. Famous artists such as Riza-i Abbasi and Muzaffar 'Ali were nurtured in the courts of sixteenth century Tabriz. However, by the eighteenth century, political instability and invasions from Afghanistan had greatly reduced the strength of the empire. The rule of Nadir Shah offered a brief retum to an imperial govemment, though the Safavid regime was too weak to keep Persia unified. The Safavid reign came to an end in 1734.

A time of political instability and invasion followed the fall of the Safavid dynasty, and these tenuous circumstances detached Persians from the cultural achievements of the previous era. The Qajar dynasty (1799-1925) reintroduced a degree of stability as it came to power, though artistic patronage was not as much of a priority as it had been under Safavid rulers. Qajar rulers did continue to commission elaborate paintings, illuminated calligraphic works, and decorative arts objects, though they favored very different types of painting than had been seen before in Persia. By this time western aesthetics had begun to pemmeate the traditional Persian visual arts. Artists began painting in oil, with an increased awareness of shading and perspective. Painting branched out in new directions, leaving the days of courtly miniatures forever behind.

It can be universally stated that the arts flourish in times of political stability and affluence. The social conditions necessary to support a vital system of patronage were essential for the creation of miniature paintings, particularly those of the Persian courts and the Mughal dynasty. Because miniature paintings required many man hours of labor and costly materials such as fine paper, pure mineral pigments, and gold leaf, an economic climate in which a measurable segrnent of the population could invest its money in patronage was essential for the success of the art form. The royal court was the primary patron of miniature painting, though in times of stability provincial officials would follow the imperial lead and commission paintings for themselves. However, the end of the imperial age also brought an end to the art form which had expressed its sensibilities with such eloquence. We are fortunate to have inherited so many of these precious images from their creators, as the circumstances in which they were produced will likely never be revisited.