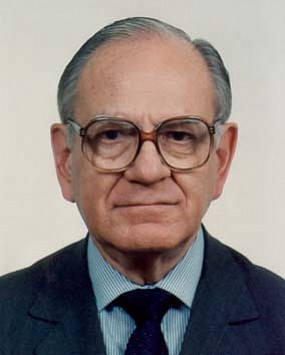

Hélio Jaguaribe (1923- )

One of the first notable Brazilian friends I met at the U.S. Embassy (first located in Rio, later in Brasília—the first air-conditioned building in South America—or so I was told. Imperialism was up to date). Because of the latter label, many of my American friends shunned it. Not I. I had many friends in the Cultural Section and among the (perhaps surprisingly) military attaches. One was an African American captain who had come to study with me at the University of Wisconsin (Interestingly, most of his fellow officers on that training program chose campuses in Florida or sunny Arizona). Based on his close association with Brazilian Army officers, my former student, now a friend, shared with me stories of the reactionary political thoughts of a few of them (carefully guarded portraits of Adolf Hitler). There are lots of ways to learn about your adopted country.

Hélio Jaguaribe was one of the most dynamic Brazilians I have ever known. He was the son of a general (who, with the legendary Marshal Rondon, had been responsible for making contact with Indians in the Brazilian heartland) and who became a leading organizer of Rio intellectual life in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Later he had a foray into the political world (less successful).

Garrulous and highly personable, Hélio was one of the friends from whom I learned the most about Brazil. Like many of my Brazilian friends, he ran afoul of the military (they didn’t like intellectuals). He went with his family into exile in the U.S. but I got him a Visiting Professorship at Harvard. As a low Assistant Professor, I had limited powers. In those salad days universities had funds to pay visitors. He settled in the Government Department (Harvard was above mere “Political Science”). He was a popular teacher and found a handsome home in Wellesley.

What I learned from Hélio was much, among other things about Brazilian culture, in the broadest sense. And that was a phenomenon he did much to change, starting in the 1950’s.

Hélio was the sparkplug in organizing a privately funded think tank called ISEB, the Higher Institute of Brazilian Studies, founded under the Kubitschek administration. Ideologically it was quite eclectic but it was principally reformist, to the center left. Among its distinguished members were Marxists and Corporatists. It sponsored lectures and widely attended forums. Its publications were widely distributed. It offered a breath of fresh air in an era of antiquated political parties. Naturally it provoked the fury of the traditional right. That helped to push Hélio into exile after 1964.

He had a very wide range of thought. When he got to Cambridge he launched into writing a history of political thought, beginning with the Greeks and the Romans. He was decidedly pleased when it was later published by a major U.S. publisher.

I remember one day when he invited me to lunch at home with his wife and very animated daughters. My Portuguese was quite fluent that day. I told them it was because I was glued to their local T.V. They smiled.

Further Readings

Jaguaribe, Hélio. Economic and Political Development: A Theoretical Approach and a Brazilian Case Study. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968

Jaguaribe, Hélio. Brasil: crise e alternativas. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1974.

Jaguaribe, Hélio. A Critical Study of History: Special Volume. Río De Janeiro: Instituto de Estudos Políticos e Sociais, 2000.

Hélio Jaguaribe was born in the city of Rio de Janeiro. In 1953, Jaguaribe and other social activists founded the Brazilian Institute of Economics, Sociology, and Politics (IBESP), where Jaguaribe worked as Secretary-General and Director. He also devoted his efforts to the publication of IBESP’s magazine, Cadernos de nosso tempo, which focused on sociological and economic issues. In 1955, the members of IBESP, including Jaguaribe, helped establish the Higher Institute for Brazilian Studies (ISEB). In 1964, after publicly criticizing the military dictatorship, Jaguaribe traveled to the United States, where he taught at Harvard University and MIT. In 1996, he received the Grand Cross of the National Order of Scientific Merit. He was later awarded the Order of Cultural Merit by the Ministry of Culture in 1999.