< 1.1 Brazilwood – 1.3 Captancies-General >

The first Portuguese settlers of Brazil were not seeking a colony in which to live, but rather a trading post. Portugal’s small size and population made sending its citizens to other parts of the world impracticable, so the country established a worldwide network of military-defended trading forts that harnessed local labor to bring resources to merchants, who in turn brought those foreign products to the European market.

Portuguese fortified trade posts were called feitorias, meaning “factories.” The merchants using them dealt in a number of different goods: primarily brazilwood, but also more exotic items such as parrots and animal skins. They were all-encompassing sites of business, serving as markets, warehouses, customs houses, and support sites for navigation. But as the French, Spanish, English, and Dutch increasingly clashed with the Portuguese over trade sites and routes, militarization became a key part of overseas trade.

Beginning as a series of meetings among merchants to protect their trading interests in other parts of Europe, the factory system was used to monopolize overseas trade, minimizing the manpower necessary from the country of origin and organizing the use of native labor around a particular, fortified site of trade.

Engenhos

By the 1530s, however, establishing settlements overseas became necessary to defend countries’ trade. The Portuguese Crown began granting land holdings in Brazil to its citizens, who financed their own voyages and made their way across the ocean to settle the land and make their fortune.

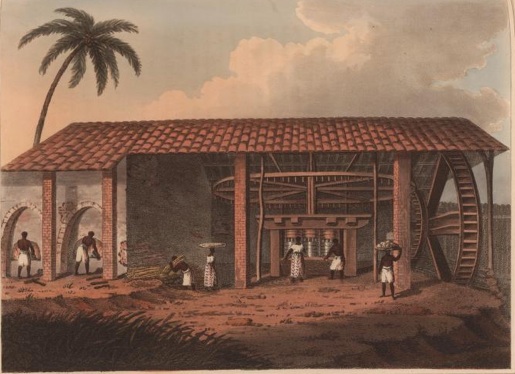

At the time of the first conquests, the principle crop of Portuguese Brazil was sugarcane. Sugar was grown primarily in the northeast, and processed in sites called engenhos, literally “mill” or “machine.” This word initially described the equipment used to refine the crop, but its definition expanded to mean the entire production unit: the latifundia, or massive farm on which sugar was grown; the house of the colonizing master and the senzala, the smaller huts where his slaves lived; the family chapel; and the buildings and equipment where sugar was processed. A large engenho typically employed about fifty slaves, as well as horses and cattle. The slaves were responsible for harvesting and processing sugar, but also for producing food and clothing for the white family they served and cleaning and maintaining the house.

Not all sugar production was overseen by laypeople. The Society of Jesus, which came to Brazil in 1549 under Manuel da Nóbrega, established a system of aldeias, or villages in which they educated and converted the native peoples of Brazil. Eventually, the villages relied on plantation-style slave labor by indigenous peoples to work the Jesuits? cattle ranches, cotton fields, and crops of sugar. So important was indigenous labor to the Jesuits that, not wanting to compete for manpower, they petitioned the Portuguese Crown to prevent colonists from enslaving the natives as early as 1548.

This painting, from 1816, shows slaves working the sugar mill at an engenho. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library’s Archive of Early American Images.

Life in the Engenho

The following is an account from a French cotton buyer in Pernambuco, Louis-François de Tollenare, who observed the various races and classes involved in agriculture in the colony and how they interacted. In his analysis, he identifies different classes of free men, from the wealthy landowners to the landless itinerant workers. Tollenare later discusses the customs of different groups of slaves on the large sugar plantations:

I will divide the inhabitants of these regions into three classes (I am not speaking of the slaves, who are nothing but cattle). These three classes are:

1. The owners of sugar mills [senhores de engenho], the great landowners.

2. The lavradores, a type of tenant farmer.

3. The moradores, squatters or small cultivators.

The sugar-mill owners are those who early received land grants from the crown, by donation or transfer. These subdivided grants constitute considerable properties even today, as can be seen from the expanses of 7,000 and 10,000 acres of which I spoke earlier; the crown does not have more lands to grant; foreigners should be made aware of this.

?

Those [slaves] coming from Africa have their shoulders, arms, and chests covered with symmetrical marks, which seem to be made with a hot iron, and the women also display these marks. For clothing the men are given a shirt and some breeches, but these garments evidently make them uncomfortable, and few preserve them, particularly the shirts. Most of the time they are satisfied with tying a rope around their loins from which hangs, both in front and behind, a small piece of cloth with which they try to hide that which modesty does not permit them to display.

The children also get clothing, but they make quick work of it so that they can go about naked. When they reach fourteen or fifteen years of age they are beaten with switches to make them more careful. At that time some are seen wearing their shirts hung over one shoulder in the fashion of Roman patricians, and, seen thus, they are reminiscent of Greek statues.

The blacks employed in domestic service, or close to their masters, dress with less elegance and more in the European manner. They take care of their breeches and shirts and sometimes even possess a waistcoat. Gonçalo had an embroidered shirt, and when he wore his lace hat and small trinkets which I had given him his pride was greater than that of any dandy; but when we went out hunting, his greatest pleasure was to leave at home his necessary and unnecessary items of clothing (Tollenare 78-87, 93-96).

- What was the role of a slave in a sugar mill, or engenho? How did the assignment of slaves to different tasks in engenhos reflect their position within the slave hierarchy?

- What was the role of Tollenare, the author of this account? How might his position within northeastern Brazilian society have shaped his view of that society?

Role of Sugar in the Brazilian Export Economy

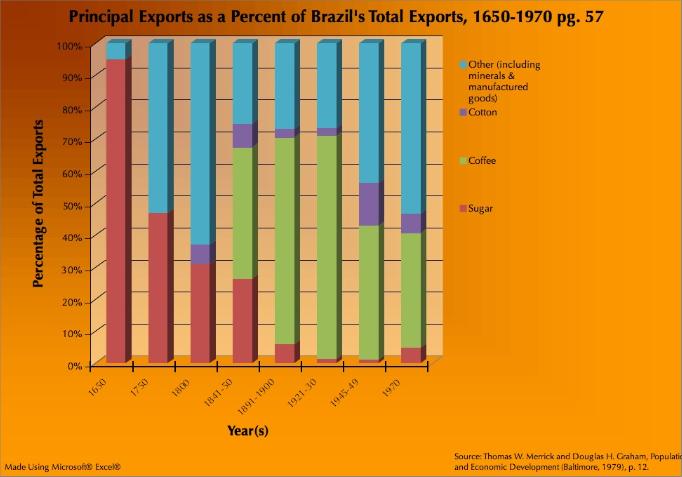

Data from Skidmore, Five Centuries of Change, p. 57.

This graph illustrates the extent to which certain materials dominate Brazil’s total exports at different periods in the country’s history. Sugar and coffee both dominate at different points, sugar dropping dramatically in importance after the colonial period. The percentage of “other” exports grows significantly when mineral deposit are exploited (the gold rush of the mid-eighteenth century, for example) and during and after World War II, when Brazil began exporting raw materials like rubber and quartz in exchange for financial, military, and technical assistance from the United States. Finally, the story of coffee in this graph is particularly telling: coffee becomes 41.4 percent of exports in the 1890s, up from zero forty years earlier.

- What are the social and economic conditions that arise from the fact that almost always over half (if not almost all) of Brazil’s exports are raw materials?

- Further, what conditions arise from the fact that Brazil has frequently had one product that dominates its total exports?

Further Reading

- Gilberto Freyre’s Casa Grande e Senzala (frequently translated as The Masters and the Slaves), for many years considered the definitive work on Brazilian slavery, discusses the relationship between masters and slaves on colonial sugar plantations.

- Alida Metcalf’s Family and Frontier in Colonial Brazil looks at the development and decline of sugar processing in colonial Brazil, complicating Freyre’s vision by introducing other classes and characters ? such as poor whites, freed blacks and mestiços, and single women owning slaves ? to the traditional model of the plantation master, his large family, and the community of slaves working for them.

Sources

- L.F. de Tollenare, Notas dominicaes tomadas durante uma residencia em Portugal e no Brasil nos mannos de 1816, 1817, 1818. Parte relative a Pernambuco (Recife: Empreza do Jornal do Recife, 1905), pp. 78-87,93-96. In Children of God’s Fire, pp. 63, 70-71.