By the end of the 19th century, cracks were beginning to show in the Brazilian economy. Since its colonial beginning, the country had depended in turn on one of a series of raw products ? brazilwood, sugar, gold ? as the export which had formed the base of its economy. The social structure of the country was dominated by a land-holding elite of European origin, who benefited enormously from African, indigenous, and mixed-race labor, first through slavery and, even after abolition.

This economy, which focused on the extraction of natural resources, offered little incentive for industrial development. While the rise of coffee as the next cash crop did not completely reverse the cycle of the colonial, feudal, extraction economy, it did encourage industrialization, help to develop a middle class in the country, and devalue the institution of slavery.

Changing Coats of Arms

“Portuguese Coat of Arms and Coffee Plants” (1800). Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library’s Archive of Early American Images.

- The first image is of the Portuguese royal coat of arms surrounded by indigo flowers, leaves, and a royal crown. Indigo was an important crop grown in other Portuguese colonies. How do these objects reflect Brazilian identity at the turn of the 19th century when this image was created?

- The second image shows the royal coat of arms surrounded by coffee plants, the crown, books, leaves, and flowers. How does this image relate to ‘Tinturaria Indigo’? What is the significance of the depicted objects?

Coffee Exports in Context

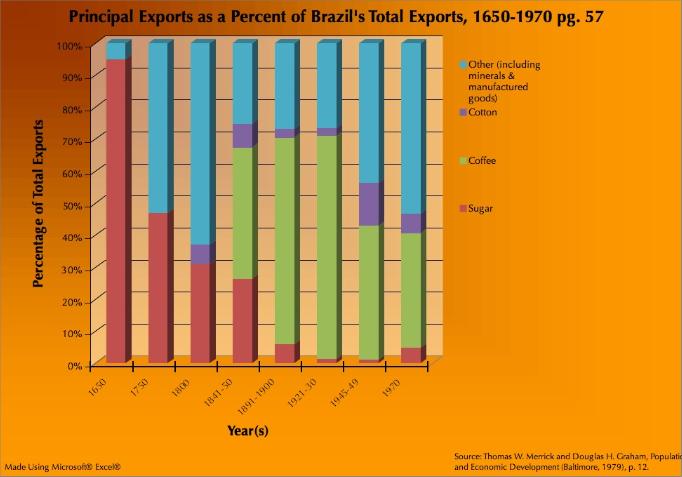

This graph can also be seen on the “Feitorias and Engenhos” topic page. It illustrates the extent to which certain raw materials dominate Brazil’s total exports at various periods in the country’s history. Sugar and coffee each dominate the economy at certain points, sugar dropping dramatically after the colonial period. Coffee’s growth and domination of the market was particularly dramatic; coffee comprised 41.4 percent of exports in the 1840s, after playing no part in the economy 40 years earlier.

- What was the result for Brazil’s economy and society in general of the country’s continued reliance on raw material extraction?

- What conditions arise from the fact that Brazil has frequently had one product that dominates its total exports?

Coffee and Changing Demographics

Until the 1880s, coffee was grown primarily in the Paraíba Valley, north and west of Rio de Janeiro, and in the northeast. The methods used for this harvest were similar to those used on sugar plantations ? slave labor-fueled production on a large fazenda owned by a single landowner. However, as demand spiked and coffee growers exhausted the fertile soil of these regions, production moved south into the state of São Paulo.

Since the 1860s British engineers had been building a railroad from the port of Santos to the interior of São Paulo, and the growth of coffee in this region spurred the development of new rail lines. Coffee estates popped up in the interior, but the owners of these estates were very different from the fazendeiros that had previously dominated sugar and coffee production.

In this photograph, coffee is shipped from the port of Santos to Europe, likely after a journey via railcar from plantations in São Paulo. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The coffee barons of the late-nineteenth century were a prime example of the growth of the urban (or semi-urban) bourgeoisie that arose out of the new capital flooding the economy with coffee’s success. They were more politically engaged than the older landed aristocracy, who were far removed from the political centers of the country, and they favored as a labor source the immigrants who were coming to Brazil over African slaves. They were an important interest group encouraging the abolition of slavery, and they provided much of the incentive for the wave of immigration from Europe that revitalized the coast in the late 19th century. The growth of coffee in São Paulo corresponded with the centralization of power in the center-east.

Coffee Exports and Value

As this graph shows, the period between 1870 and 1909 was prosperous for Brazilian coffee producers. Between 1909 and 1910, however, there was a sharp drop in the value of coffee and a corresponding drop in the number of sacks exported. This corresponds well to the previous graph outlining the central role that coffee took as Brazil’s main export during this time period.

Further Reading

- The Brazilian Economy: Growth and Development by Werner Baer gives a more detailed analysis of the beginning and development of the coffee economy, its relationship with Brazil’s other cash crops, and its role on the country’s economic development today.

Sources

- Baer, Werner. The Brazilian Economy: Growth and Development. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2008.

- Eakin, Marshall. Brazil: The Once and Future Country. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.