The Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Brown University created a digital collection of Latin American travel accounts written in the 16th-19th centuries. Foreign natural historians and explorers often traveled to Brazil during this time period and wrote about their experiences and perceptions of Brazil. These works were disseminated broadly and contributed to Brazil’s image abroad. A full list of Brazilian travelogues can be found here.

Once, in a child’s dream, I wandered into a Fifth Quarter of the world, and found every thing different from all previous knowledge; as only children or old folk desire it to be. Now the dream has come true.

Thus Rudyard Kipling, famed British poet, novelist, and traveler, begins his Brazilian Sketches, of 1927. This lush travelogue recounts a European’s impressions of an exotic Latin American “world apart,” scattered with mountain fazendas, snake farms, and elaborate seaside estates?a world, according to its reporter, with more in common with Cape Town or Bombay than with Paris or New York.

Modern and Primitive

At the same time Kipling presents Brazil as an exotic colonial realm, he observes with wonder the tropical nation’s incorporation of the technology of the North Atlantic. In the early years of the Brazilian Republic, the nation’s leaders were focused on developing industry and technology in order to put it in the same league as the industrialized nations of North America, countries Brazil claimed as its equals.

Throughout the Sketches, Kipling indicates the incongruity of Brazilian development with that nation’s exoticism. He finds it strange that his Brazilian companions in transatlantic transit should reside “beyond the limits of imagination?among the snows and fires of the Cordilleras, or in sweating forests northward,” and still exhibit signs of progress.

Or did one desire cities as progressive as Birmingham, with Opera and Town Halls, and racecourses of limitless cost and size? Or still green worlds of coffee; or whispering, dark cocoa-nut plantations where old houses were hidden beside old, old chapels, and one could catch a breath of what life used to be in the days of the superb Brazilian Empire? Or suburban railways that corkscrewed themselves up the faces of 3,000 foot mountains; or Transcontinentals that rumbled nightly over the Andes, and fed you rather decently en route? These things, and heaps more, were to be played with; and the men of the cattle, coffee, shipping, oil, rail, and all the other interests, said, and meant it, that they would give one a good time. But time was quite good enough as it came up day after day with the ripening warmth, under escort of squadrons of flying fish always rounding-to across our steady bows (Kipling, 7).

Images of the Wilderness

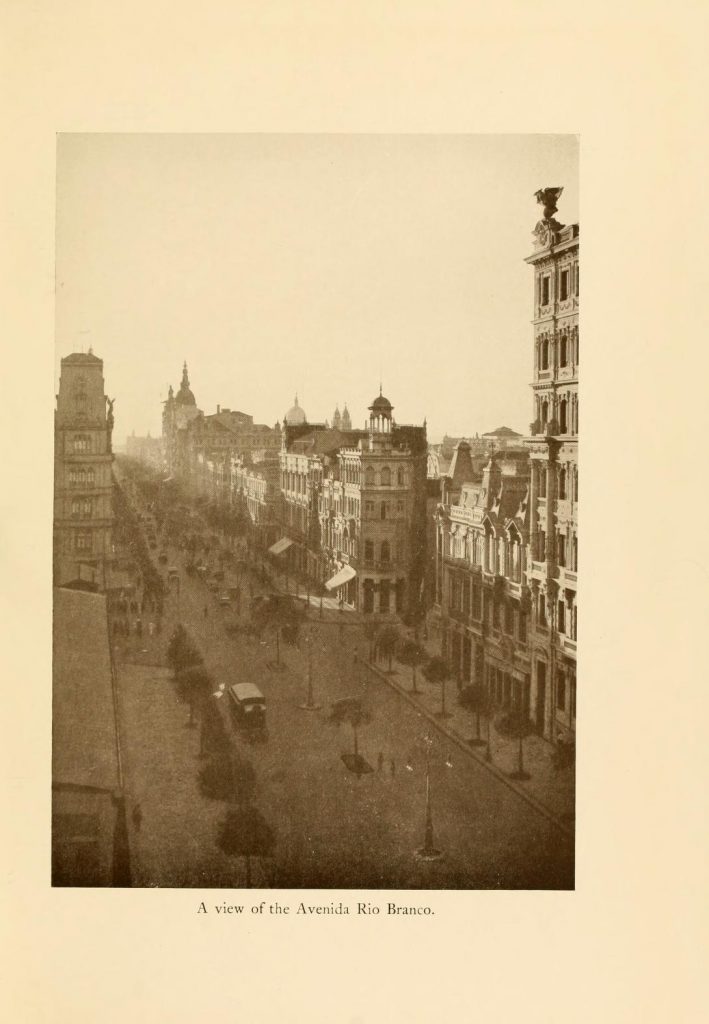

For Kipling, the Brazilian wilderness was always encroaching upon the possibility of real modernity, even in a city as large as Rio de Janeiro. A nighttime drive into the city’s center was marked by a tension between the modern?electric lights and motor cars?and the primitive?the mountainous jungles looming over the city.

In sane countries there is no hurry, not even for Port Doctors and Police. Thus, though we entered Rio harbour by early afternoon, it was not till the edge of dusk that we sidled into the wharf, and the whole city and the coasts alongside her chose that moment to light up in constellations and cloud-stars of unbridled electricity ?

? This world of light gave of a sudden, between the shoulders of gigantic buildings, on to even vaster spaces of single-way avenues, between trees, with the harbour on one side, fringed by electric lights that raced forward, it seemed for ever, and renewed themselves in strings of pearl flung round invisible corners; while, above everything, one saw and felt the outlines of forested mountains.

Such encroachment finds a more literal expression in Kipling’s description of the hydroelectric power station in the mountains above Santos and the railway used to arrive there. Here, the conditions of the jungle threaten to hinder the function of modern contrivances. For Kipling, the Brazilian wilderness would always be at odds with the Western machine.

There must be worse railway country in the world; but I had not seen any. Every yard of those fallacious mountain-sides conspired against man from the almost vertical slopes out of sight above, to the quite vertical ravines below. One could not help admiring the fiend’s own skill with which water always attacks the weakest points of trestle-abutments, tunnel-mouths, and curves. All pitches and banks were flashed, stoned, concreted, and, where possible, diverted; the guttering was ample as town-cisterns and the culverts corresponded. All ground that offered room for anything, except a snow-shed, had been brought into the fighting-line. Nothing in Nature was trusted to stay put or to be left unwatched. And there were steel trestles that launched out across gulfs where you could drop a hundred feet into fifty-foot forests before your rolling-stock really began to roll? .

We had risen seven or eight degrees of heat in a quarter of an hour’s drop. When we reached the flat ground near Santos and the respectable loco who took us there; the shut mountains behind us showed no sign by, or through, what miracles we had descended (92).

The Imperial Legacy and Progress

Enhancing the sense of exotic wonder throughout the Sketches, Kipling fills his descriptions with language linking Brazil to other colonies. The atmosphere of Santos is compared to “that of Southern India,” while activity along the bustling port takes place, according to Kipling, “beneath the brassy glare of a West African sky.” The clubs of São Paulo, meanwhile, “mix memories of Bombay and Calcutta” with the air of “Johannesburg in the old days.” Such comparisons reflect Kipling’s own background?he was born in India and traveled throughout the British Empire. That his foreign perspective differs so greatly from the contemporary view within Brazil?which sought to place the country among the ranks of modern, industrial nations?indicates an imagined European supremacy heightened by the history of imperialism as much as it suggests the developmental challenges endemic to Brazil.

Certainly, these are characterizations that contemporary Brazilians would have contested. Brazil in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had a keen interest in technological development styled after the industrial nations of the North Atlantic. The coffee boom of the previous century had spurred the development of a railway system, while the quest for national unity made a telegraph and a system of roads seem essential. In the transition from empire to republic, making these projects the enterprise of the Brazilian government and not foreign companies became paramount. As early as 1866, one English observer was noting with approval the changes made in urban planning.

Rio, at one time, was proverbial for its filthiness, but, of late years, much has been done to facilitate the traffic and improve the sanitary condition of the city. The streets have been carefully paved with squared stones, the roads in the suburbs well macadamized, and a magnificent system of sewerage has been inaugurated, and in part completed, under the practical skill of Mr. Gotto, the engineer of the Company; but there is still needed the great desideratum?a large supply of water to make the working perfect, which, however, will no doubt be obtained, as the Government is doing all in its power to improve the sanitary state of the city (Scully 151?2).

There are signs of this burgeoning industrialization beneath even the colonial expressions of Kipling’s Sketches. The foreign firm operating the railway between São Paulo and Santos, for instance, was required by its charter to reinvest a determined portion of its dividends into domestic infrastructural improvement. Such measures echoed the policies implemented under the presidency of Floriano Peixoto three decades prior to Kipling’s visit that promoted an economic transition from agriculture to industry by establishing protective tariffs and encouraging capital investment. What is more, Brazil by the 1920s was deeply enmeshed in international trade; Kipling’s description of a wharf at Santos, “where all the world’s steamers were unloading goods,” and his mention of coffee export to Europe provide two notable instances. It seems that exotic isolation was a myth recognizable as such even to the author.

Nor were contemporary Brazilian intellectual and artistic figures ignorant of their European counterparts. Kipling’s brief mention of the orientation of younger Brazilian writers toward France does little justice to the assimilation and adjustment of European modernism to local conditions. That the artists at 1922’s Semana de Arte Moderna were familiar enough with European styles to transform them into forms distinctly Brazilian reflects simultaneously a proud awareness and powerful critique of European trends.

Though Kipling’s descriptions of exotic Brazil exaggerate its backwardness, by the 1920s the country still had not achieved full independence either economically or culturally. Most of the Brazilian industrial technology recorded by Kipling?railway infrastructure, in particular?was meant to hasten and cheapen the processing and export of coffee. Furthermore, Brazil’s participation in the global economy involved a large degree of dependence on foreign imports. The poetic epigraph to the sixth section of the Brazilian Sketches encapsulates the situation:

Such as in Ships and brittle Barks

Into the Seas descend

Shall learn how wholly on those Arks

Our Victuals do depend.

For, when a Man would bite or sup,

Or buy him Goods or Gear,

He needs must call an Ocean up,

and move an Hemisphere (79).

Yet, in general, the Brazilian Sketches gloss over this complexity. In Kipling’s travelogue, Brazil is cast as a simple backwater, a primitive jungle threatening to swallow up the few instances of modernity daring men have erected in its wilderness. But the Brazilian Sketches still direct valuable attention to the challenges facing Brazil by the third decade of the twentieth century. Infrastructural unification and industrial development demanded attention, and cultural identity remained in flux. Thus it becomes clear that Brazil was neither as exotic as Kipling suggested, nor as Western as its native modernizers hoped. A new set of problems accompanied this middle stage of development. These awaited the attention of President Getúlio Vargas.

Further Reading

- Darlene Sadlier’s Brazil Imagined examines representations of the country from the 1500s to the present, discussing the role of artistic representation in shaping its national identity.

Sources

- Kipling, Rudyard. Brazilian Sketches. New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1940

- Scully, William. Brazil; its provinces and chief cities: the manners & customs of the people; agricultural, commercial, and others statistics, taken from the latest official documents. London, Murray & co.: 1866. Available through the Brown University Library and the Department for Latin American and Caribbean Studies’ collection of Latin American Travelogues.

<Previous: 5.2 Modern Art Week and the Rise of Brazilian Modernism