The Portuguese-born Brazilian singer Carmen Miranda gained a huge following when she moved to the United States and adopted an exotic, pan-Latin American persona. Above, the singer in a scene from the 1953 film “Morrendo de medo.” Courtesy of the Brazilian National Archive.

The Second World War and Shifting North American Focus

The United States government acutely felt the need for some sort of cultural exchange with Brazil in the build-up to World War II. Vargas’ regime, which moved toward fascism and extreme nationalism in the mid-1930s, bought arms from Germany after being turned down by the United States. But Brazilian elites felt more cultural affinity for the Allies, and the country had important natural resources it could trade to the allied nations at very favorable terms.

In 1936 U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt visited Brazil and spoke to the national Congress. Roosevelt discusses the change in direction of American policies over such issues as the United States’ connections to Cuba; the symbiotic relationship Roosevelt sought to create with Brazil through his “Good Neighbor” policy; America’s desire for Brazil to modernize; and Brazilian nationalism.

It has been a great privilege for me to make the acquaintance of your President. I have had the privilege of knowing some of his family before today and I hope that in the not too distant future we shall be able to welcome President Vargas at Washington as a visitor in the United States.

May I say a word about communications? I have always felt that the advent of the airplane, the advent of quicker steamship service is going to make a large difference in the future relationships of the Americas because science is going to make it easier for us to get to know each other better and people who know each other well can be friends. So in the days to come I hope very much that we shall have more news of Brazil in the United States (Garcia).

Roosevelt’s peaceful visit to Brazil represented a change in American foreign policy, which had been plagued by recent violence in Cuba. Yet America’s new turn toward diplomacy was not simply altruistic. The growing threat of Nazi Germany and Brazil’s hitherto ambiguous foreign policy led its leaders to court a stronger relationship. Roosevelt aimed to improve relations with its southern neighbor in order to guarantee Brazil’s support in the war effort.

Brazil would not actually offer its support until 1942, after the United States’ response to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor and Germany’s failed invasion of Russia tipped the odds clearly in favor of the Allies. Late as it was, Brazil’s entry was cause for celebration in the United States, as this newsreel demonstrates:

Postwar Cultural Exchange

As it secured an alliance with Brazil in the war, the United States saw an opportunity to further its economic interests in the country. One way of doing this was by furthering Brazilians’ exposure to American culture, a project that was well under way by the beginning of the war. Between 1928 and 1937, 85 percent of films shown in Brazil came from Hollywood.

But in the years after the war, the U.S. government sought to build stronger cultural ties by bringing representations of Brazil to an American audience as well. Multimillionaire Nelson Rockefeller became the head of a new office that recruited studios and filmmakers to make films with Brazilian features and targeted at a Brazilian audience.

Walt Disney rose to the occasion, creating a new character that was a caricature of Brazilian life: a samba-dancing, cigar-smoking parrot named José–Zé to Brazilian audiences–Carioca, who served as a sidekick for Donald Duck in Saludos Amigos, where the American duck met Spanish- and Portuguse-speaking friends on a trip to Latin America. Zé Carioca delighted Brazilian audiences, inspiring his own spin-off cartoons in Brazil.

Americans were clearly fascinated by certain aspects of Brazilian culture, but the culture they were observing was shaped by Hollywood, exoticized, and often confused with that of Brazil’s neighbors. Journalist Katharine Brush wrote about such misrepresentation in a 1942 Washington Post article:

I hate to argue with the movies, and with the magazine-article writers, and with the Messrs. Shubert—but I’m afraid the time has come. Now that the Brazilians are our allies in this war, I feel that somebody should rise to state that (1) Brazil is not all scenery, and that (2) it isn’t always Carnival Week in Rio de Janeiro; and that (3) practically nobody down there looks at all like Carmen Miranda—and practically nobody dresses like her, as far as that goes.

“The rich, deep, Brazilian Music”: Carmen Miranda, Samba, and Exotic Brazil

Carmen Miranda, perhaps the most recognizable Brazilian star of the twentieth century, certainly looked an exotic figure in many of her most famous performances—dancing with tropical fruits on her head, or dressed all in white and draped with gold and silver jewelry while singing “O que é que a baiana tem?” (What does the baiana—a girl from Bahia—have?)

Yet Miranda herself was appropriating a culture not her own. Fair-skinned and Portuguese by birth, she became famous singing and dancing to samba music, which adopted African rhythms and symbols. Identifying herself as from Bahia, a center of Afro-Brazilian culture, she presented a sort of racial democracy that was not reflected by opportunities available to Brazilians of different ethnicities at the time. She was not alone—samba was being appropriated at the time by a number of famous singers and became identified with Brazil as a whole. Orson Welles, visiting the country in 1942, called samba “the rich, deep, Brazilian music rolling down to Rio from the hills,” a reflection of his belief that the purest samba came from the favelas in the hills around the city.

In 1939, after ten years as a successful samba singer in Brazil, Carmen Miranda was invited to the United States as part of Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” policy, which encouraged cultural exchange between the two countries. Beginning as a stage performer in New York before moving to Hollywood to star in movies, she increasingly performed her songs in English and incorporated other countries’ musical traditions, such as Cuban rumba, into her act. Many scholars have argued that Miranda was stereotyped as a Latin female of mixed race—sweet, sexually available, and compliant. At the same time, in crafting a persona that appealed to her American audience and its desire for an exotic display, she can be seen as a shrewd analyst of trends in popular culture.

While begun as a project to ensure Brazil’s support in World War II and later to establish favorable trade conditions, the United States government’s focus on cultural exchange grew into a much broader cultural phenomenon as each country grew fascinated with images of the other. Yet the image of Brazil held by American audiences and producers—seen both in the ways Americans appealed to a Brazilian audience, and in the supposedly authentic Brazilian culture made available in the United States—placed an emphasis on the country as an exotic paradise and created an essentialized vision of the country that did not match its real ethnic or cultural composition.

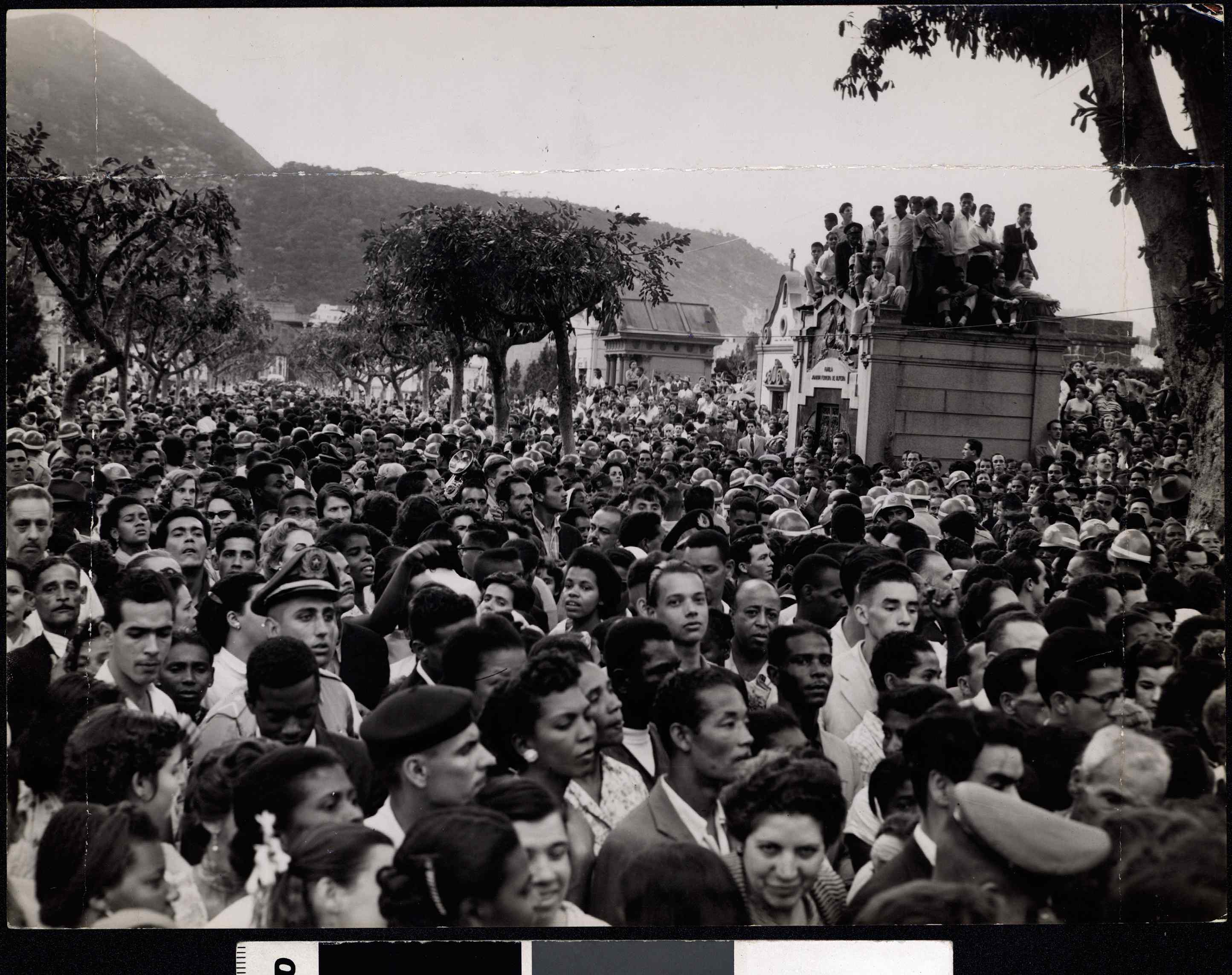

Despite her waning popularity within Brazil after “selling out” to American producers, Carmen Miranda’s death was a caused mourning on a massive scale. In this photo from Correia da Manhã, crowds pour into the cemetery as her body is brought to Rio de Janeiro to be buried. Courtesy of the Brazilian National Archive.

Further Reading

- Antonio Tota’s The Seduction of Brazil: The Americanization of Brazil during WWII explores the influence of the United States on Brazil before and after the war, looking in particular at the formation of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs, led by Nelson Rockefeller.

- Martha Gil-Montero’s Brazilian Bombshell is a biography of Carmen Miranda and gives a fuller account of her rise in popularity in Brazil and the United States.

Sources

- McCann, Bryan. Hello, Hello Brazil: Popular Music in the Making of Modern Brazil. Duke University Press: Durham and London, 2004.

- Brush, Katherine. “Out of My Mind: Our Allies the Brazilians.” The Washington Post. 31 October, 1942.

- Garcia, Frank M. “Roosevelt Pledges Peace But Warns ‘Agressors’; Warmly Greeted in Brazil.” The New York Times. 28 November, 1938.