During the Brazilian “Old Republic” of 1889-1930, the disparate regions of the country were generally uninterested by and at times even unaware of the national government. The first two leaders of the republican government, Marshal Deodoro da Fonseca and Marshal Floriano Peixoto, got their start in the military; Peixoto forced Fonseca to resign by threat of force before assuming power.

For the next 30 years, the military would play a key role in the consolidation of the national republic. Yet while military thinkers professed their faith in democratic politics, their lack of confidence in real-life politicians and their belief in their own righteousness combined to make them see military intervention as necessary and good for the nation. As the historian Dirk Kruijt writes,

Acting as the explicit protector of constitutional order, the military establishment placed itself above the law and order of everyday society, and thus legitimized its intervention into the political arena (10).

Placing itself above the law and intervening in politics would be a consistent trend in the Brazilian military—from providing aid to peasants in the interior, to rising up against its own hierarchical structure and the elitism of the national government, to establishing a new regime with a broader base of support, to overturning that government when it became unpopular.

The Guerra do Contestado and the Harsh Reality of Regional Inequality

The Guerra do Contestado [Contestado War], of 1912–1916, was a major conflict between peasant settlers of the interior and landowners in the region, who were supported by two-thirds of the Brazilian army brought in to suppress the uprising. Like the rebellion at Canudos in 1897 (which was chronicled by Euclides da Cunha in his book Os Sertões), the Contestado was the result of an uprising among devoutly religious peasants led by a charismatic leader who prophesized an end of times, and it showed that 15 years after Canudos there was a vast gap between the urban coast and the rural backlands which the military could not have fathomed before it entered the region.

The region in which the Contestado rebellion was fought was in the far west of the country, on the border with Argentina, making it both inaccessible and essentially foreign to soldiers raised and trained on the eastern coast, which more resembled the cities of Europe than its own interior at the beginning of the twentieth century. From Diacon 570.

The Contestado War convinced many military leaders of the need for direct federal intervention in the hard-to-reach regions of the country. General Setembrino de Carvalho proposed the creation of a new state, “Iguaçu,” carved from the states of Paraná and Santa Catarina in the heart of the war zone, that would be ruled by a strong military governor supported by federal troops. This interventionist policy had multiple motivations: the proximity of the region to Argentina making internal revolt particularly dangerous, the power to provide direct assistance to the poor and dispossessed of the region, and a more exalted position for the military.

The nationalist current in the military can be seen in the pages of the military journal A Defesa Nacional, which viewed the military as a key tool of development, modernization, and national unity. As early as 1915, the magazine was criticizing the failure of the civilian government in this respect: “May the example of army bravery and death in the Contestado serve as a lesson to the timid and indifferent citizens of Brazil.” That view of military high-mindedness would consistently inform its involvement in politics.

World War I and Factions Within the Military

While a large portion of its own army was wrapped up in internal warfare, Brazil watched as the armies of two countries it had long idealized, Germany and France, clashed. Some in the Brazilian army wanted to enter the fighting, though it was not clear on which side: ideologically, many recognized that Germany had violated international law, but economically, Britain’s blockade of German trade hurt Brazil’s foreign business interests.

Ultimately, Brazil joined the war effort against Germany in 1917, sending a small force to serve alongside the French on the Western Front and a larger one to join the naval battles in the Atlantic. Neither force saw substantial action, however; they served almost exclusively as medical personnel, and the war ended with Brazil remaining aloof from the action and from commitment to the cause of any one nation.

The soldiers who served at the time of World War I, like these cavalry soldiers, came out of the war with the belief that the military was a necessary stabilizing force in any nation that had not yet reached the highest level of civilization. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In the years after the rise of the Positivist Church in Brazil, a reform fever had caught hold that made many officers focus on education and positivist philosophy. This group was made up of men who called themselves “doctor” and read poetry. Another school was made up of men who worked their way up through the ranks and prided themselves on their illiteracy, focusing instead on leading the troops.

The young officers of the decades around World War I were part of the same movement as the officers who published A Defesa Nacional. Unlike the two groups that came before, they mixed formal education with the practical use of tactics in warfare. They saw the army as a social leveler, beginning to train petty officers—corporals and sergeants—to directly train recruits. Olavo Bilac, a noted poet and journalist, was a key proponent of a mandatory conscription law that was passed in the first decade of the century and began to be enforced in the 1910s. Bilac was not always a strident supporter of mass conscription; in 1907, in a bit of prescience not seen in his later writing, he warned of the law’s dangerous potential effects:

It is not difficult to predict the commotion the Obligatory Military Service Law will produce amid this population that has always been horrified by the pack and the gun. When the Paraguayan War broke out … recruitment, already euphemistically referred to as “volunteering,” spread indescribable fear from the coast to the interior … On the day that the Obligatory Service Law is put into effect, it will cause the same panic and fear in our countryside that it did in 1865 (Beattie, 219).

At that time, Bilac was feeling the effects of persecution by the government of Floriano Peixoto. By 1915, with a civilian regime that favored him, he was one of the most outspoken writers in favor of universal conscription. In an address to students at a São Paulo law school, Bilac, who had never served in the army, extolled its virtues as a nationalizing, disciplining, and modernizing force on the individual:

What is universal military service? It is the complete triumph of democracy; the leveling of social classes; the school of order, discipline, and cohesion; the laboratory of self dignity and patriotism … The cities are full of unshod vagrants and ragamuffins … For these dregs of society, the barracks would be a salvation. The barracks are an admirable filter in which men cleanse and purify themselves: they emerge conscientious and dignified Brazilians (230).

The Tenente Revolts

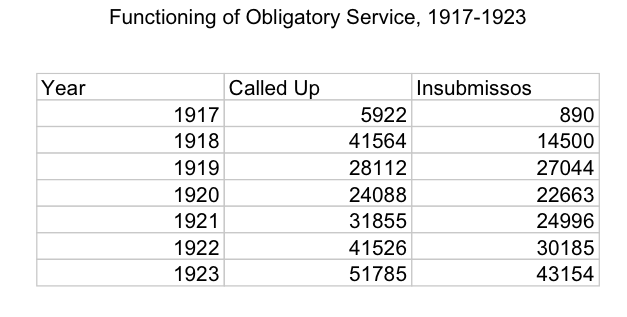

Ironically, the middle-class, lower-ranking officers whom Bilac idealized in his plan and who gained power and status from the Young Turks’ reforms were growing increasingly discontented in the years after the end of the first World War. There were so many of them (in 1920, 65.1 percent of the officer corps was made up of second or first lieutenants) that it could take over a decade for an officer to rise through the ranks. A national depression after the worldwide price of coffee sank affected these officers as much as it did civilians. Adding to their discontent was the lowered prestige of the military in the eyes of civilians, the product of increased forced conscription in the previous decade. As the number of conscripted soldiers rose, so too did the number of insubmissos (literally refusing to submit), those who ran away or hid to avoid their military training. This response may have been difficult to accept for the petty officers, who were closest in the social hierarchy to the recruits who blatantly rejected their chosen profession.

The result of this discontent was the first Tenente Revolt in 1922. A group of tenentes, or lieutenants, rose up at Fort Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro, protesting the imprisonment of Marshal Hermes da Fonseca by the president of the Republic and demanding a series of social changes, including the nationalization of mines and agrarian reform. The rebels at Fort Copacabana and in other barracks scattered across the nation were crushed by loyalist forces, and the government declared a state of emergency.

Two years later, the problems highlighted by the tenentes had not been resolved. Exactly two years after the first Tenentes Revolt, another group of soldiers in São Paulo rose up against their superiors. This rebellion was better organized than the first and intended to overthrow the government of President Artur da Silva Bernardes. The rebels gained control of the city of São Paulo before being cast out by federal forces. Labeled the “Prestes Column” after their leader Luis Carlos Prestes, they marched through the backlands attempting to incite a peasant rebellion. Finally, after the army repeatedly tried to stamp it out with no success, the Prestes Column marched across the border to Bolivia, seeking refuge.

The eighteen tenentes leaders after leaving the Copacabana fort on 6 July, 1922. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The revolts fought against the system of “Café com leite” [coffee with milk] politics that had held sway throughout the Old Republic. The name refers to the principal crops of São Paulo and Minas Gerais; the president would come alternately from one of these two regions, with the oligarchical central government and regional powers rigging the results to make sure these two powerful states and the political interests within them were placated. This left all but the wealthy elites powerless to make any changes through the political sphere, and the growing discontent of the middle class was articulated through the petty officers’ revolts.

These revolts did not end the system of concentrated power. In fact, as the economy sank and public discontent grew in 1929 and 1930, Paulista President Washington Luis chose as his successor another politician from São Paulo, its governor, Júlio Prestes. This was enough of a tipping point for diverse interests throughout the country to unite, overthrowing Washington Luis and changing the entire political system.

- The Tenente Revolts came at a time of modernization and reform that were designed to benefit the lower-ranking members of the military. Why did the petty officers choose to revolt in this context?

The Revolution of 1930 and the Military Under Vargas

The revolution that put an end to the Old Republic and established the first fifteen-year presidency of Getulio Vargas, a land-owning politician from Rio Grande do Sul, was brought about by a very loose coalition of interests—politicians and landed elites from states other than São Paulo, who felt their power slipping; the urban middle class, who were educated but kept out of politics; a small number of active-duty army officers; and former members of the Tenentes Revolts, who joined hesitantly with many of the same elites and army officers they had been rebelling against.

Gétulio Vargas and his advisors in 1930. He stands at the right in a full military uniform. From the San José State University Department of Economics.

The revolution left the army in shambles, its command structure disintegrating as officers rose up against their commanders. Many of the tenentes returned to serve in the army, elevated in rank due to their service in the revolution, but they were openly disrespectful to their superiors. At the same time, after the removal of President Washington Luis and his government, it was the only national institution the central government could control.

After the initial coup, Vargas struck a deal with Washington Luis’s regime to determine the new government democratically. Yet the military was now recognized as a political entity with a direct role in politics; that role was to intervene whenever army leaders perceived some slight to their institution. Late in the decade, statesman Oswaldo Aranha would remark, “[E]verything has to do with the army.”

The Constitutional Revolt and Resumed Nationalism

An uprising in São Paulo two years after the establishment of the post-revolution provisional government led to further changes within the armed forces. Immediately after 1930, the young officers who had participated in the revolution experienced particular recognition of their key role in the change of power. The suppression of the São Paulo rebellion, however, was a victory for the army as a whole, diminishing the role of the tenentes and providing an argument for the value of military discipline and institutional unity. The military police of São Paulo and a volunteer force could not stand up to the might of a unified national army.

The motivation for the revolt was, immediately, to demand that President Gétulio Vargas, who governed a provisional government unbound by a constitution, turn the government of the state over to civilian politicians and abide by a new Constitution. However, it was rooted in the deep-seated resentment of that state in its loss of prestige and soon came to advocate for the overthrow of the federal government. Vargas’ government emphasized rumors that the revolutionaries wanted São Paulo to secede to mobilize nationalist fervor against them.

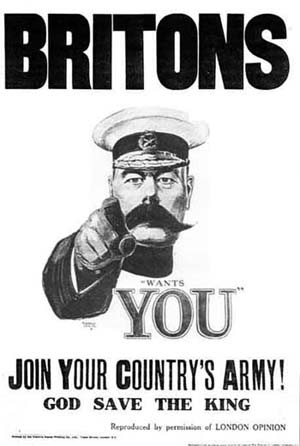

“Lord Kitchener Wants You,” a famous British WWI recruiting poster, inspired many copycats in other countries seeking to recruit for the war effort. From Wikimedia Commons.

Uncle Sam was a famous image on recruiting posters in the United States. From the United States Library of Congress.

Below on the left, a recruiting poster for the 1932 São Paulo revolt, shows a member of the state militia telling the viewer, “You have a duty to fulfill.” On the right, 1937 Integralist poster stating, “Brazil needs you!” Both clearly imitate earlier posters from Britain and the United States that called on those countries citizens to fight. They indicate virtually opposing positions: the uprising against encroachment by the federal government and the need for utter commitment to the nation, respectively.

A recruiting poster from the Paulista revolt reads, “You have a duty to fulfill. Consult your conscience!” Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A 1930s Integralist poster reads, “Outside of Integralism there is not nationalism.” From the Arquivo Público do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

A new political party, the Ação Integralista Brasileira [AIB, the Brazilian Integralist Action], formed in the aftermath of the São Paulo revolts and the declining prestige of the tenentes. The Integralists were an ultra-nationalist paramilitary group that drew support from middle-class army and navy officers. They took a hardline moralist position informed by “Christian virtues” and enforced by authoritarian government policy, and in 1934 they began a series of street brawls with the rising Communist movement led by former tenente Luis Carlos Prestes.

When the suppression of the Communist threat gave Vargas the rational to establish dictatorial powers, the Integralists initially supported his move to the far right. However, AIB leader Plínio Salgado (a member of the 1922 Modern Art Week) angered Vargas with his express presidential ambitions, and the president turned against the movement. After a failed armed attempt at seizing power in 1938, the movement dissolved into a number of different factions. However, many Integralists would reemerge in the 1960s as part of the coup that overthrew President João Goulart and established the military regime.

- In what ways were the ideologies of the Tenente Revolts and the Integralist movement similar and different?

- What changes in Brazilian military and political culture could account for the differences?

Further Reading

- Shawn Smallman’s Fear and Memory in the Brazilian Army and Society, 1889–1954 discusses army censorship and control of its own records in the creation of political myths, challenging the “official story” of the army’s role in politics during these years.

Sources

- Diacon, Todd. “Bringing the Countryside Back in: A Case Study of Military Intervention as State Building in the Brazilian Old Republic.” Journal of Latin American Studies 27:3 (Oct. 1995).

- Kruijt, Dirk. “Politicians in Uniform: Dilemmas about the Latin American Military.” European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies No. 61 (December 1996), 7–19.

- Rachum, Ilan. “From young rebels to brokers of national politics: The tenentes of Brazil (1922-1967)”. Boletín de Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Carbie No. 23 (December 1977), 41–60.