History of the Movement Before the Coup

The student movement existed prior to the military coup of 1964 and had already set a precedent for protesting against the government and establishing its presence as an independent political entity. The União Nacional de Estudantes (UNE) was formed in a national convention on August 11, 1937. Its manifesto established the group as a representative student organization that advocated for the interests of Brazilian students, bringing the fragmented group from all over the country under one cohesive national assembly. After the second Conselho Nacional de Estudantes in 1938, President Getúlio Vargas began to take a particular interest in the organization as a way to help unify national identity.

The National Union of Students (UNE) advertises plans for a national student fair. From Ultima Hora, courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

The formation of UNE helped lend a sense of empowerment to students: it was possible for them to become a force of change within the country independent of their parents, professors, and administrators. From the start, UNE was a left-leaning, anti-fascist entity. The first tension between students and the government came with World War II, when UNE protested the country’s continued neutrality and refusal to denounce the Axis powers; the Brazilian government declared war on Nazi Germany that same year.

By the late 1940s, UNE had shifted its focus from Brazil’s international actions to its national concerns. From 1947 to 1950, students aligned themselves with the Brazilian socialists, and to a degree with the outlawed Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), in order to organize and participate in a series of strikes supporting nationalization of the oil industry. The demonstration’s slogan was “O petróleo é nosso” (The petroleum is ours), and it was the first of many protests in which the main catalyst for action was Brazilian nationalism and weaning the country from international—especially American—influence.

In the early 1950s, the group moved away from socialism and aligned with the much more conservative União Democrática Nacional. At the same time, a new, more radical student organization, the União Metropolitana dos Estudantes, rose up in Rio de Janeiro, uniting nationalists, communists, socialists, and workers. But by 1955, UNE returned to its leftist roots, joining forces with this group under an ideology of progressive radicals. Led by UNE President José Batista de Oliveira Júnior, they organized a strike against higher trolley fares and, at a conference in Bahía in 1960, pledged to fight for the democratization of higher education not only in Brazil, but in all of Latin America. The Brazilian government had yet to clamp down on UNE’s activities, which gave the group the courage to continue pushing boundaries. In 1962, one-third of the Brazilian student population went on strike to promote democratization of higher education and to open more spots for students who passed university entrance exams.

While the student movement sympathized with the politics of President João Goulart, who was elected in 1963, they found it important to assert their independence from the national government. They maintained that their allegiance was always and only to the Brazilian people. As such, they participated in campaigns for literacy and sanitation reforms in the nation’s rural areas, and they found artistic venues that gave them a space to pose questions and produce positive works of art that encouraged social change. It was the birthing ground of a new Brazilian popular culture that was at once radical and universal, giving students the agency to explore their impact on the greater intellectual community.

After the election of Goulart as Brazil’s president, conservative forces in the government—afraid of growing socialist and communist forces—began targeting all radical social movements, including the student movement. At first their radical actions only intensified, but with the wave of repression and direct government intervention, they felt the same limitations that restrained the rest of the country.

The Military Coup

On March 13, 1964, Goulart held a very public and very large rally in downtown Rio de Janeiro, signing two laws that promoted the tide of social mobilization, which terrified the military: nationalizing all private oil refineries and addressing agrarian reform. The military, fearing a new communist Brazil that would lose the support of its foreign allies, organized a coup d’état so sudden that there was no way for the left to react. On March 30, troops in Minas Gerais rose up, and when Goulart was unable to quell dissent, he abandoned his post for fear of further violence.

Outside of the radical wing of UNE, most students did not oppose the coup in the beginning. Jean Marc von der Weid, one of the last presidents of UNE, explained this original confusion and the disillusionment that would follow:

I was not the only student to support, ingenuously and actively, Governor Carlos Lacerda and the battle against what we believed to be a threat to liberty. Two years later we found out—my middle class and I—that democracy was what we had known before and that what we really had done was support the implantation of a dictatorship (Filho, 158).

For the student movement, the “revolution” of 1964 marked only the beginning of a wave of repressive reform that isolated and further militarized university students. On the day of the coup, the building housing the headquarters of UNE was burned down, a sign of intimidation that aimed to scare students into a more submissive role. Former students Antônio Noronha Filho and Pedro Meira explained the level of the intimidation they felt:

On April 1, 1964, the military coup showed instantaneously its view of the students. Without the legal government, UNE was invaded, sacked, burned in a climax of hate that escapes the purely political realm and falls in the psychiatric sphere.

This was the first of many acts by the military to terrorize students. Universities and other educational facilities suffered greatly from intervention. Once UNE was outlawed, students were left without their old venues of organization and representation. The military’s approach to handling students was to give them a “shock treatment” to expel their sentiment of rebellion and erase any inclination toward subversive activity. But that destruction and threat to its existence as a political identity gave the student movement the momentum necessary to militarize and fight back.

MEC-USAID

The MEC-USAID accords, finally agreed upon in 1968, were a catalyst for major student action even before their adoption. The Ministry of Education and Culture, under Presidents Castelo Branco and Costa e Silva, was in talks with the United States Agency for International Development to acquire loans for a new systematization of the Brazilian university structure, which would include the privatization of state universities and the adoption of English language programs in elementary schools. UNE, in its early years, had been a champion for the democratization of Brazil’s education, and the threat that MEC-USAID posed was enough to provoke bitter and violent protests from students. It was seen as the climax of American intervention in Brazil’s affairs.

Lei Suplicy

From April 1964 onward, all student groups and academic centers were shut down, and the military had the authority to arrest any professors suspected of supporting communism. The Lei Suplicy de Lacerda, authorized on November 9, 1964, eliminated UNE and replaced it with the Diretório Central de Estudantes, an organization created by the government for the government, as a mask for a democracy that no longer existed. All strikes and political propaganda were prohibited, making it nearly impossible for students to express their views on the regime. Students who still claimed allegiance to UNE refused any form of dialogue with the dictatorship, accusing it instead of using the law for corruption and oppression.

1966: A Precursor to Violence Yet to Come

1966 was the first year in which tensions exploded on a national scale between students and the government. The national police, newly formed under the department of homeland security, was charged with keeping the peace and handling protests. Students began to strike in March of that year, but it was in July that they took their largest action yet. In response to the violence of the Security Department, the military occupation of national universities, and the failure of the Diretório Central dos Estudantes, the students decided to hold the twenty-eighth congress of UNE clandestinely in Belo Horizonte. On July 28, 1966, 300 student delegates came together and agreed to take control of the political education of Brazil’s students. UNE’s new president João Luiz Moreira Guedes pledged to sustain the organization’s legacy of fighting against authoritarian rule:

It will not be through decrees that the government impedes the organization of the Brazilian university students through their highest authority; since the burning of the headquarters of UNE, in April of 1964, and despite all the decrees of the government, this entity never stopped existing for even an instant, belying those who attributed its survival to the budget of [the Ministry of Education and Culture].

According to the president of São Paulo’s União Estatal dos Estudantes, Joaquim de Carvalho, it was a victory for the people that this Congress was able to meet; the students were pioneers in the fight for freedom from the military government.

Yet this moment of freedom was short-lived. That same day, 5,000 policemen in 400 police cars came to the Congress to disband the meeting. The police would strike against students again soon afterward. In a raid in September 1966, the military police arrested 178 students. Student organizers felt increasingly jaded and antipathetic toward the government. UNE called for a general strike that would start on September 18 and end on the National Day of Resistance to the Dictatorship, September 22.

On September 23, 600 students gathered in the Medical School of the federal university in Rio de Janeiro to protest the imprisonment of fellow students, the Lei Suplicy, and suspensions of university professors. The police threw gas bombs into the crowd and barred the doors of the university. One hundred and ten students were injured and sent to military hospitals to receive further “treatment.” Colonel Darcy Lazaro, commander of the military police, explained, “The Military Police of Guanabara has orders to act with serenity, firmness, and correct behavior in the face of the esteem that the students, and the general public, earn from us.”

Protests at the Universidade de Brasília

Few universities suffered as much as the University of Brasília, which was subject to many police incursions and administrative changes at the whim of the government. Before the coup, Minister of Education Darcy Ribeiro had implemented a policy that began pushing forward the model of education reform UNE had been pursuing for so long. Less than a month after the coup, the Policia Militar de Minas Gerais invaded the university, arresting professors and disposing of administrators suspected of “subversive” beliefs. Zerefino Vaz was placed as temporary director, functioning more like a government watchman to keep the students in order.

Federal tanks and soldiers roll into the Federal University of Brasilia after a major protest by students. From Ultima Hora, courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

By October 1965, the thin lines of cooperation between the regime and the students collapsed. Students held public protests against the destruction of their formerly modernized university, the dismissal of professors, and the rise in tuition. On October 20, the military police were again called in to “remedy” the situation, forcing their way onto campus and reacting violently to the protests. If students or professors did not obey, they were considered subversive and consequently persecuted. Many students were harassed, and 15 professors were fired, sparking a strike among the more than 200 professors left at the university. Books were confiscated and some even burned. Of the 16 students arrested, two were brutally injured.

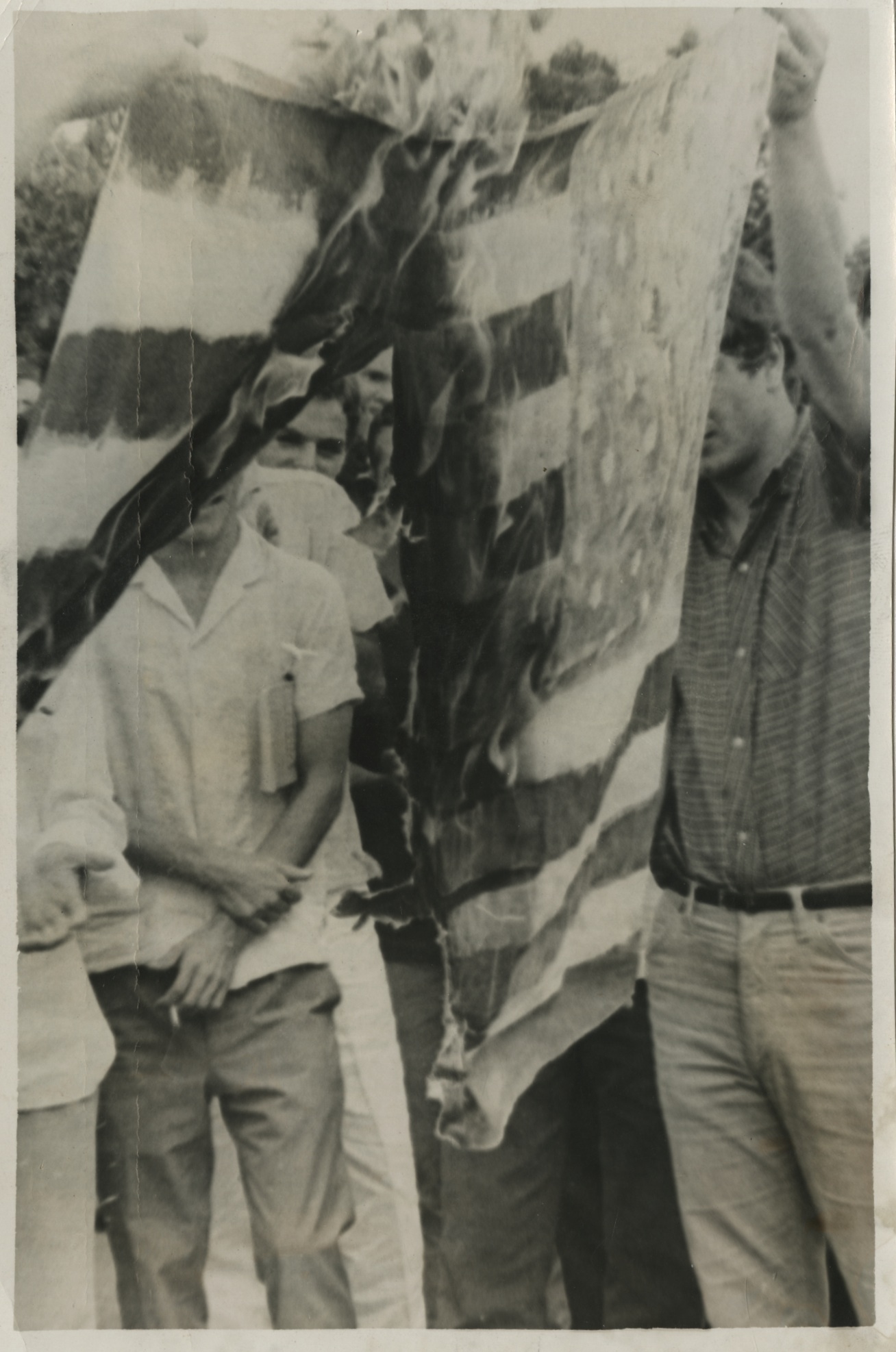

Fed up with the privileged place of the United States and the continued encroachment of the federal government on their campus, students at the federal university in Brasília gathered together in 1967 and set fire to an American Flag. From Ultima Hora, courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

The University of Brasília came back into the national spotlight less than two years later, with the arrival of American ambassador John Tuthill, who was to give a speech there on April 20, 1967. He was welcomed by student protests against the war in Vietnam and the ongoing controversy over MEC-USAID. As the protests intensified, agents of the Department for Political and Social Order (DOPS) were called in to intervene. This attack triggered student protests in bigger cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, where strikes developed into a more general challenge against the technological deficiencies of university equipment and the obstacles impeding educational modernization.

On April 24, 1967, students in Brasília gathered together and burned an American flag. In doing so, they not only expressed their repulsion toward American involvement in Brazil’s educational system, but also demonstrated how they could be pushed to aggression by police violence. The intervention of DOPS agents had been an additional violation of their trust—their campus was supposed to be a safe haven for education and expression. By this point, the strength and dedication of their network had increased tremendously from the beginning of the military regime.

1968 and Brazil in the Eyes of the United States

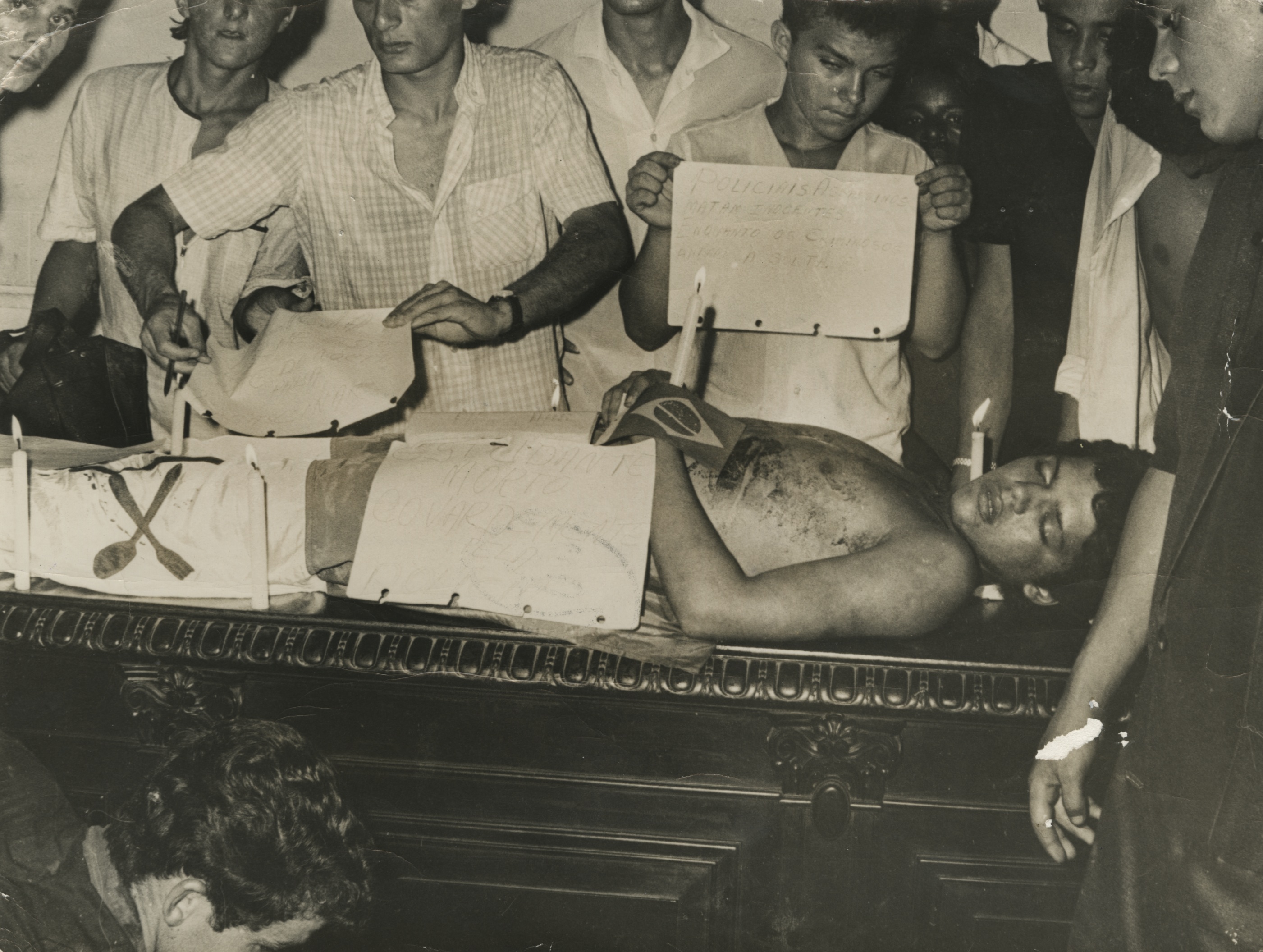

Protesters mourn the death of high school student Edson Luis at his funeral, which was held in front of the Legislative Assembly in downtown Rio de Janeiro. From Ultima Hora, courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

During a protest on March 28, 1968, police killed a high school student participating in the protest. This proved a powerful catalyst—over a weeklong period that followed, there were 26 protests in 15 different cities. The protests awoke again that June, culminating in a march of 100,000 in Rio de Janeiro. That year was a turning period for the student organizations in Brazil, which afterwards split into two camps along lines of what tactics they found acceptable.

The Brazilian student protestors were not alone; they were part of an international explosion of student action in 1968. From the United States to France to West Germany to Italy to Czechoslovakia to Brazil, student protests shook societies and students saw themselves as part of a global struggle.

The United States government saw the international dimension of the protests, and the CIA devoted a classified document, called “Restless Youth,” to the issue. The CIA document attributes student protests to a cycle of protest and police repression, the communist leanings of students, the lack of democracy practiced in Brazil, and the inadequate stance of the country’s leader at the time, Costa e Silva. It focuses on the inadequacy of the country’s education system without focusing on the root causes of the widespread protest within society at large, which included not only the students, but also workers and the church. The document focuses on issues of dissent through the lens of the stability of the Brazilian government, which reveals the primary motivation of the United States in Brazil, one of its key South American allies.

Read the entire declassified document, “Restless Youth,” here.

The document claims that radicals can manipulate a student protest against “police excess” into “a demonstration against the ‘dictatorship’ of foreign control” (CIA 9). This statement fails to recognize the totality of the government’s reach into the lives of its citizens and that police repression was part of a large, dictatorial, system of control by the military state apparatus. Yet it does recognize that the protests were by 1968 supported by a broad coalition of workers, students, and clergy, and that popular support for the movement would not have surfaced had the “government moved to implement needed reforms” (CIA, 10).

The CIA report provides an accurate assessment of the effectiveness of students’ tactics:

Student demonstrations, no matter how well-organized and widespread, will not bring down the government. Mounting student and military frustration with government inaction, however, does not bode well for even short-range stability in Brazil (CIA, 11).

The report places the student movement within the context of stability, reserving power to severely disrupt the government with the military. In the context of the global instability caused by international student movements, an adequate understanding of the threat, or lack thereof, that the Brazilian students posed to the government was extremely important to a United States government, for whom stability was a primary goal in its foreign policy.

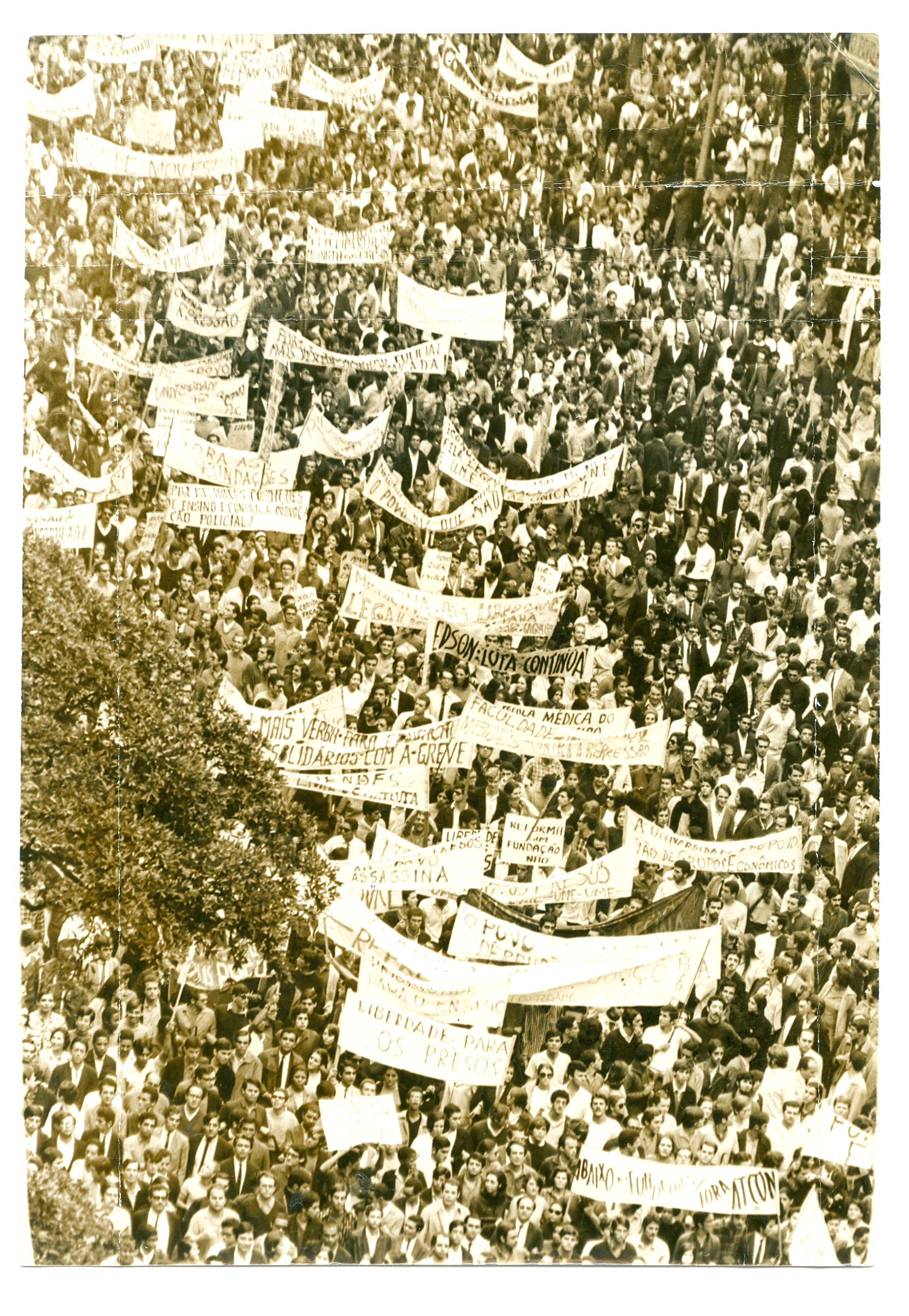

The March of the One Hundred Thousand, which occurred in Rio in June 1968, prompted serious concern over public action from the military government and led to the adoption of Institutional Act Number 5. From Ultima Hora, courtesy of the Arquivo do Estado de São Paulo.

After 1968

Institutional Act No. 5, the strictest instance of government repression and the culmination of a series of decrees mandating surveillance, censorship, and centralized authority during the military regime, was issued in December 1968. While not directly the result of student protests, the act came in response to a general sense of upheaval put into motion by the march in Rio de Janeiro and other demonstrations.

The draconian laws and close monitoring of campuses that followed this institutional act largely ended widespread campus protest; after this point, organizers within the movement who favored continued, violent action went underground, while others found their activities so restricted that any public demonstrations halted for the next few years.

Further Reading

- Phyllis Parker’s Brazil and the Quiet Intervention, 1964 looks at U.S. involvement in the coup through presidential records, tracing the United States’ records and investigations into many levels of Brazilian society, including organizing among university students.

Sources

- Araujo, Maria Paula. Memórias Estudantis: Da Fundação da UNE aos Nossos Dias. Rio de Janeiro: Ediouro Publicações S.A, 2007.

- Filho, Joao and John Collins. “Students and Politics in Brazil, 1962–1992.” Latin American Perspectives. 25:1 (1998).

- Martins Filho, João Roberto. Movimento Estudantil e Ditadura Militar, 1964–1968. Campinas, São Paulo: Papirus Livraria Editor, 1987.

- Skidmore, Thomas. The Politics of Military Rule in Brazil, 1964–85. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.