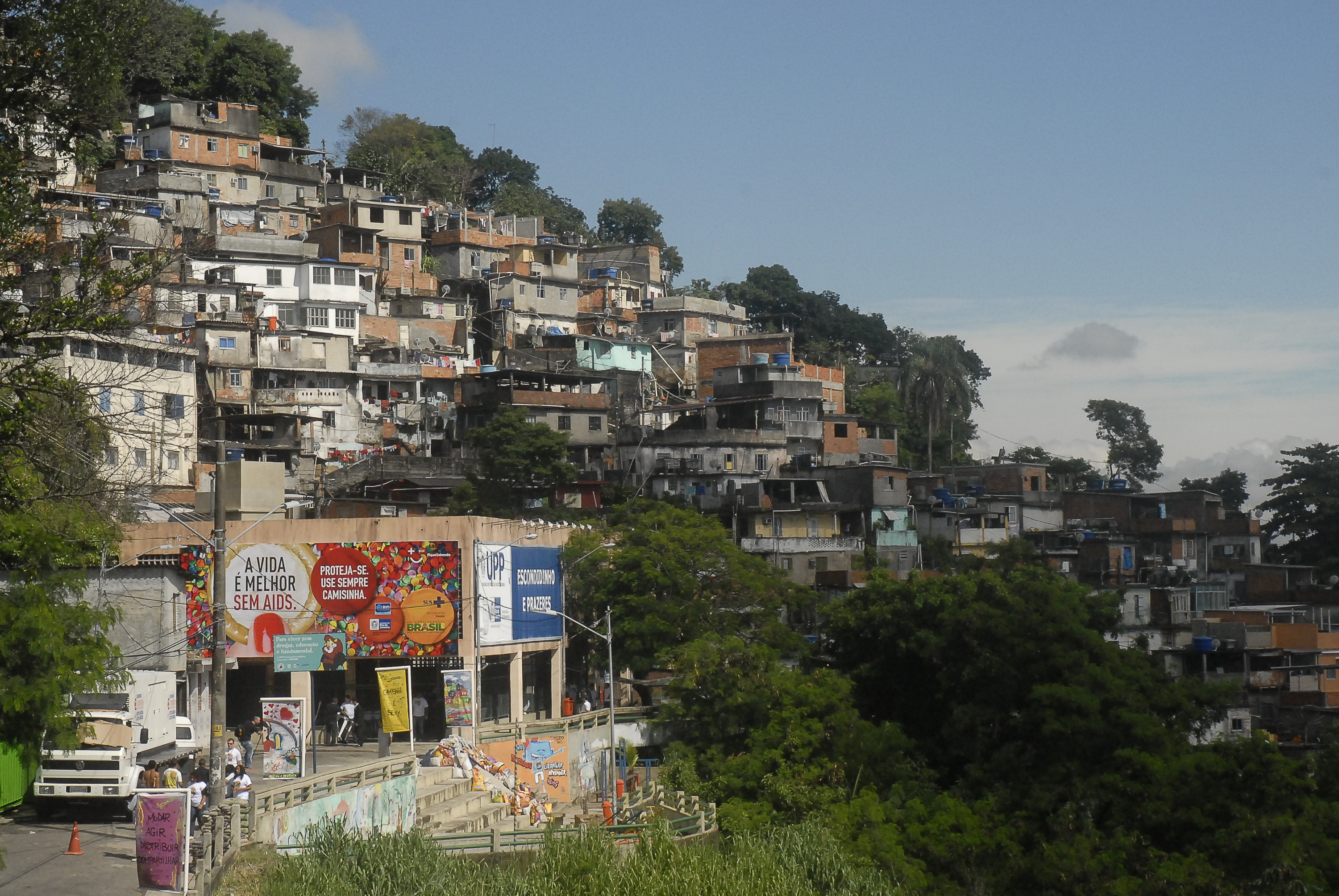

History of HIV/AIDS in Brazil

The health ministry launched a national campaign for AIDS prevention at Carnaval in 2013 with the slogan “A vida é melhor sem aids. Proteja-se. Use sempre a camisinha” (Life is better without AIDS. Protect yourself. Always use a condom)

When the first case of HIV/AIDS was reported in Brazil in 1982, the country was in the midst of a transition from a repressive military dictatorship to a democratic nation.[1] This process of transformation, known as the ?abertura?, opened government and political institutions to democratic procedures. The abertura, as well as other underlying sociopolitical and economic changes of the time, would profoundly affect not only the spread and migratory pathways of HIV/AIDS but also the overall national response to the epidemic. While the disease was initially considered a severe threat to national health and remained subject to intense stigma and discrimination, Brazil today is heralded as a model of a successful response to the epidemic, particularly for countries of low- and middle-income status. Ultimately, in the creation of a robust response to HIV/AIDS, Brazil and the National AIDS Program (NAP) in particular have increasingly utilized a rights-based approach to disease prevention and treatment.

The transition from a military regime to a democratic state in the 1980s occurred in tandem with the initial outbreak of the disease and had a profound impact on the subsequent governmental response. Various social movements protesting the regime at the time had a strong influence in the establishment of a legal framework for health care that would set a precedent for AIDS policy. One such movement, the sanitary health reform movement, was a group of primarily leftist, middle class health professionals that sought equal access to health services for all Brazilian citizens.[2] The sanitaristas essentially supported an approach to medicine that emphasized the social determinants of health such as poverty and access to education. The lack of effective medical care during the dictatorship only strengthened the movement?s political momentum in the 1970s and 1980s. Their efforts culminated in the legal definition of health as a universal, human right as established by the 1988 Constitution and the creation of a Unified Health System (SUS), which offers public health services and insurance to all citizens.[3] This notion of health as a human right would serve as the basis for later HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention measures.

A Rights Based Approach to HIV/AIDS Treatment

In addition to the historical activism of the sanitaristas, other social movements such as those supporting feminist, gay, and black causes were among the many groups firmly advocating for political transformation. Many of these movements? agendas and organizations, particularly those in support of gay rights, resembled and cooperated with the efforts of AIDS activists.[4] Brazilian medical anthropologist João Biehl explains:

AIDS and gay activists framed their needs and claims as universal human rights, their actions as those of civil society at large. Their claims and practices of solidarity were aimed at halting ?civic death? and maximizing the ?right to life.? AIDS activists strategically activated the new legal mechanisms that the democratic constitution had put into place and made AIDS ?a socially recognizable need.?[5]

Biehl?s term ?civic death,? in this case, refers to the social process by which stigma and prejudice are severely detrimental to an individual?s ability to live healthily and normally through mechanisms such as ruining employment opportunities or the ability to find housing. It is this type of death that activists and early prevention efforts sought to avoid by emphasizing the importance of combating stigma and discrimination towards HIV-positive individuals.

The National AIDS Program, established in 1986, would respond to HIV/AIDS according to similar principles. Drawing upon the framework of universal access to health care, the Brazilian government mandated in 1996 the free, universal provision of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs). The guarantee of antiretroviral therapy was complemented by a variety of social policies that emphasized condom usage and cooperation with a national network of nongovernmental organizations. In fact, the Brazilian government currently remains the world?s largest purchaser of condoms, importing about a billion of them each year.[6] The Ministry of Health and NGOs alike frequently distribute these to low-income neighborhoods, sex workers, and partygoers throughout Carnival celebrations. Both the extensive distribution of condoms and the free provision of ARV treatment exemplify the notion of health, AIDS treatment, and HIV prevention as each citizen?s right or ?um direito seu?.

In addition to emphasizing the rights of HIV-positive individuals, other prevention measures sponsored by the Ministry of Health and NAP, such as large-scale mass media prevention campaigns, also emphasize the rights of other historically marginalized groups including gays and sex workers. These campaigns, which utilize television commercials, radio clips, and a variety of publically displayed print materials, often show gay men in romantic relationships implying toleration and acceptance of various sexualities. Similarly, sex workers, another group identified as a population vulnerable to HIV infection, receive similar treatment regarding their sexual practice and right to work. In 2002, the Ministry of Health released a series of ads, pamphlets, and radio announcements targeting sex workers that proclaimed, ?Sem vergonha, garota. Você tem profissão,? (?Don?t be ashamed, girl. You have a profession?), in order to incentivize the use of condoms among prostitutes.[7] The NAP even turned down close to $50 million dollars from the Bush administration in 2005 by claiming that the guidelines were too conservative and would hinder the treatment of infected sex workers and their clients.[8] Pedro Chequer, director of the NAP, said, ?That clause shows disrespect for sex workers. We advocate the legalization of the profession, with the right to collect INSS [social security] and a pension.?[9] Accordingly, displays of homosexuality and discussions of sex work in prevention media serve as additional instances in which an acceptance or promotion of certain freedoms are linked to AIDS policy.

Brazil?s rights based approach to combating HIV/AIDS initially emerged as a domestic policy but also eventually transformed into an international claim for recognition of the important relationship between health, human rights, and access to medicine. By the time ARVs had been developed to treat AIDS, ?AIDS activists and progressive health professionals [had] migrated into state institutions and actively participated in policy making.?[10] These officials held starkly different views from the international community in terms of the government?s role in providing free, universal pharmaceuticals. In particular, the 1996 legislation guaranteeing this provision was ill received by various multinational pharmaceutical companies, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank, and the United States.

Shortly before 1996, the Brazilian government had supported the WTO in the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) treaty that promoted unified patent protection laws and in turn prevented the domestic production of any generic pharmaceuticals patented outside Brazil after the treaty was signed.[11] In spite of TRIPS, both activists and policy makers rejected this notion by claiming that ARV prices chosen by multinational pharmaceutical companies were too high and defending the notion that universal access to medicine required reductions. According to members of the NAP, ?the [World] Bank?s pressure to not have free dispensation of medication was always in the air? and followed a ?neoliberal logic of costs and benefits.?[12] This debate came to the forefront of international politics in 2001 when the United States filed a trade dispute at the WTO and threatened to pose economic sanctions in opposition to Brazil?s pharmaceutical policy.[13]

Despite their initial reaction, however, many of these protestors eventually cooperated with free, universal distribution. Brazil eventually received a World Bank loan, AIDS Project II, of $300 million from 1998-2003 and also won their confrontation with the United States over patent legislation by pressing the international community to support global access to AIDS treatment.[14] Finally in 2002, the World Health Organization (WHO) even classified ARVs as an ?essential medicine,? almost six years after Brazil began advocating this framework.[15]

HIV/AIDS Today

Today, universal access to HIV/AIDS treatment is a well-defined goal in international discussions of health and health policy that Brazil fundamentally helped articulate. The historical involvement of a collection of civil society groups in protesting the regime and later participating in the establishment of a new government, allowed for these progressive ideas about access to medicine to shape governmental interests and policy action in opposition to international norms.

Currently, HIV/AIDS in Brazil is a concentrated epidemic remaining primarily among particular high-risk groups, yet prevalence rates have stabilized nationally over the past decade. Due to the historical cooperation between civil society and policy makers, great strides have been in not only promoting universal access to medicine but also emphasizing the relationship between health and human rights both domestically and abroad. While Brazil?s HIV/AIDS policy is not perfect and much work remains to ensure a continued, effective response to the disease, efforts under a broader framework of health as a human right has defied expectations of the international community. This rights-based approach may yet produce new reconfigurations of what is necessary in global health policy.

Sources:

- Biehl, João. Will to Live: AIDS Therapies and the Politics of Survival. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- “Brazil Turns Down US Aids Funds.” BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4513805.stm (accessed December 8, 2012).

- Galvão, Jane, et al. “How the Pandemic Shapes the Public Health Response ? the Case of HIV/AIDS in Brazil.? Public Health Aspects of HIV/AIDS in Low and Middle Income Countries. Eds. Celentano, David D. and Chris Beyrer: Springer New York, 2009. 135-50.

- “Governo Dilma Dificulta Controle Social.” Grupo De Incentivo à Vida (GIV). http://www.giv.org.br/noticias/noticia.php?codigo=2398 (accessed December 8, 2012).

- “How Condoms Could Save the World’s Forests.” The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/mar/26/forests (accessed December 8, 2012).

- Nunn, Amy. The Politics and History of AIDS Treatment in Brazil. New York: Springer, 2008.

- Parker, Richard G. “Migration, Sexual Subcultures, and HIV/AIDS in Brazil.” Sexual Cultures and Migration in the Era of AIDS: Anthropological and Demographic Perspectives. Ed.Gilbert H. Herdt. Oxford: Clarendon, 1997. 55-69.

- “Sem Vergonha, Garota. Você Tem Profissão.” Departamento de DST, Aids e Hepatites Virais, Ministério da Saúde. http://www.aids.gov.br/noticia/sem-vergonha-garota- voce-tem-profissao (accessed December 8, 2012).

[1] Jane Galvão, et al,, “How the Pandemic Shapes the Public Health Response ?- the Case of HIV/AIDS in Brazil,? Public Health Aspects of HIV/AIDS in Low and Middle Income Countries, Eds. David D. Celentano. and Chris Beyrer (New York: Springer, 2009), 135-50.

[2] Amy Nunn, The Politics and History of AIDS Treatment in Brazil (New York: Springer, 2008), 31.

[3] Nunn, 41.

[4] Richard G. Parker, “Migration, Sexual Subcultures, and HIV/AIDS in Brazil,” Sexual Cultures and Migration in the Era of AIDS: Anthropological and Demographic Perspectives. Ed. Gilbert H. Herdt. (Oxford: Clarendon, 1997), 68.

[5] João Biehl, Will to Live: AIDS Therapies and the Politics of Survival, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007., 123.

[6] How Condoms could Save the World’s Forests,” (The Guardian, 2010), accessed December 8, 2012, http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/mar/26/forests.

[7] “Sem Vergonha, Garota. Você Tem Profissão,” (Departamento De DST, Aids E Hepatites Virais, Ministério Da Saúde, 2002), accessed December 8, 2012, http://www.aids.gov.br/noticia/sem-vergonha-garota-voce-tem-profissao.

[8] “Brazil Turns Down US Aids Funds,” (BBC News, 2005), accessed December 8, 2012, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/4513805.stm.

[9] “Brazil Turns Down US Aids Funds”, online.

[10] Biehl, 8.

[11] Biehl, 74.

[12] Biehl, 66.

[13] Nunn, 125-6.

[14] Biehl, 57, 70-1.

[15] Biehl, 72.