It’s time to make the targets!

November 28, 2012 by rness | Comments Off on It’s time to make the targets!

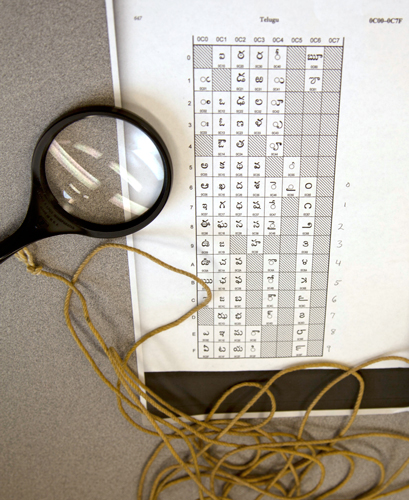

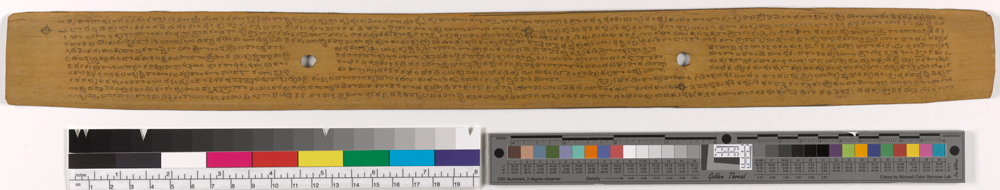

It is standard practice here in Digital Production Services to include a reference target for tone and color reproduction in each digital image capture. The target is retained in the master TIFF file, and cropped out of the derivative file. Reference targets are used to achieve accurate color reproduction by providing visual references to known swatch color values directly within digital image captures. For our department’s newest digital camera-based system, we use an Image Science Associates target, which includes a focus/sampling-rate reference scale. For reflective (flatbed) scanning, FADGI Technical Guidelines for Digitizing Cultural Heritage Materials recommend that reference targets include a photographic gray scale, a color reference, and an accurate dimensional scale. The Kodak Q-13 is recommended for the gray scale and color reference. The Q-13 color reference includes a ruler along the top edge, but because its accuracy is debatable, we substitute with a dimensional scale generated in Adobe Illustrator.

Combined, streamlined targets can be created in-house by cutting and stacking the Q-13 strips. I create two versions, a standard 8” target and a 4” mini target, appropriate for postcard sized objects.

The Materials and tools used to create the combined targets are:

-Kodak Q-13 Color Separation Guide and Gray Scales

-Laminating Sheets

-Centimeter rules [printed]

-Scissors or Paper Cutter

-Exacto knife

-Ruler

-Bone folder

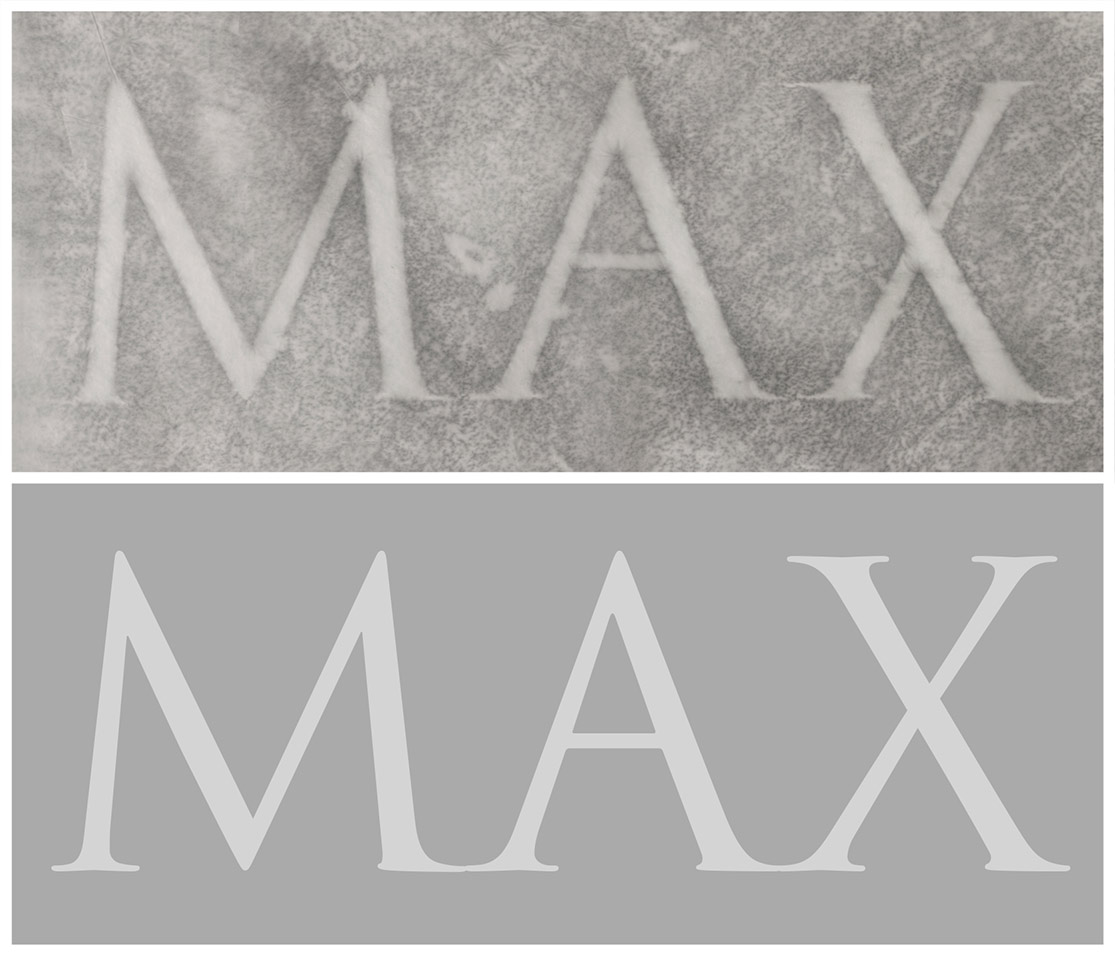

The technique I employ to create the 8” combined targets is to first cut two strips from each Q-13 color and greyscale target, and align them with the printed centimeter rule. Next, for purposes of color management, small marks should be made on particular greyscale patches. With an exacto knife, I notch the “A”, “M”, “B”, and 19 densities.

The mini-target is created by cutting down the full size targets. Include a subset of the greyscale patches (I use A, 1, 2; 6, M, 8; 15, B, 17; 19), and notch the greyscale “A”, “M”, “B”, and 19 densities.

The mini-target is created by cutting down the full size targets. Include a subset of the greyscale patches (I use A, 1, 2; 6, M, 8; 15, B, 17; 19), and notch the greyscale “A”, “M”, “B”, and 19 densities.

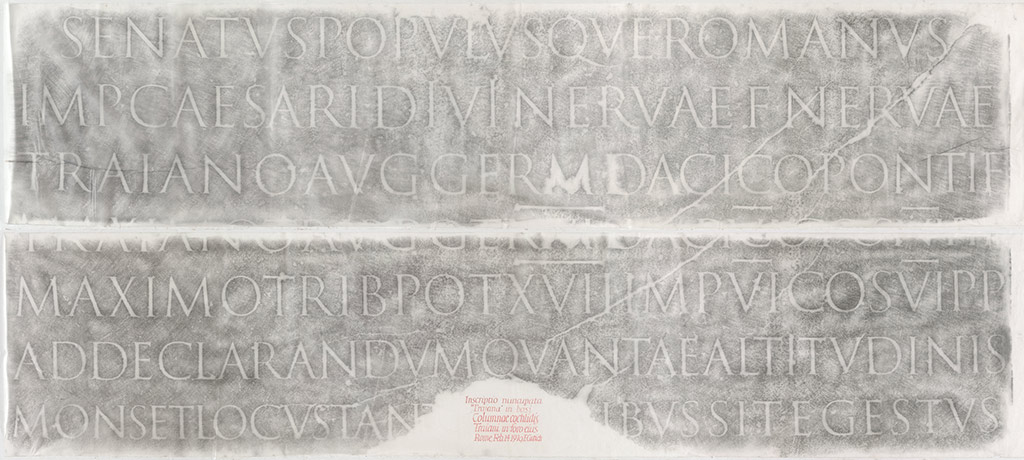

Carefully align all Q-13 segments in the order shown, and pencil in the creation date on the back of each target.

Begin the final stage of assembly by cutting laminating sheets into 4” and 2” widths. Place the target strips and dimensional reference on top of the 4” strip. Place the 2” laminate strip on top of the dimensional reference, making sure to leave the Q-13 strips exposed. Use the bone folder to increase adhesion. By making diagonal cuts as shown, the remaining laminate material below the dimensional reference will serve as a “handle” and will allow the target to be positioned without touching the Q-13 densities directly.

Even with careful handling, reference targets become soiled over time and need to be replaced on a routine basis, especially if they are used regularly. The targets are also prone to fade, and therefore should be stored away from direct light sources.

Photography: Lindsay Elgin