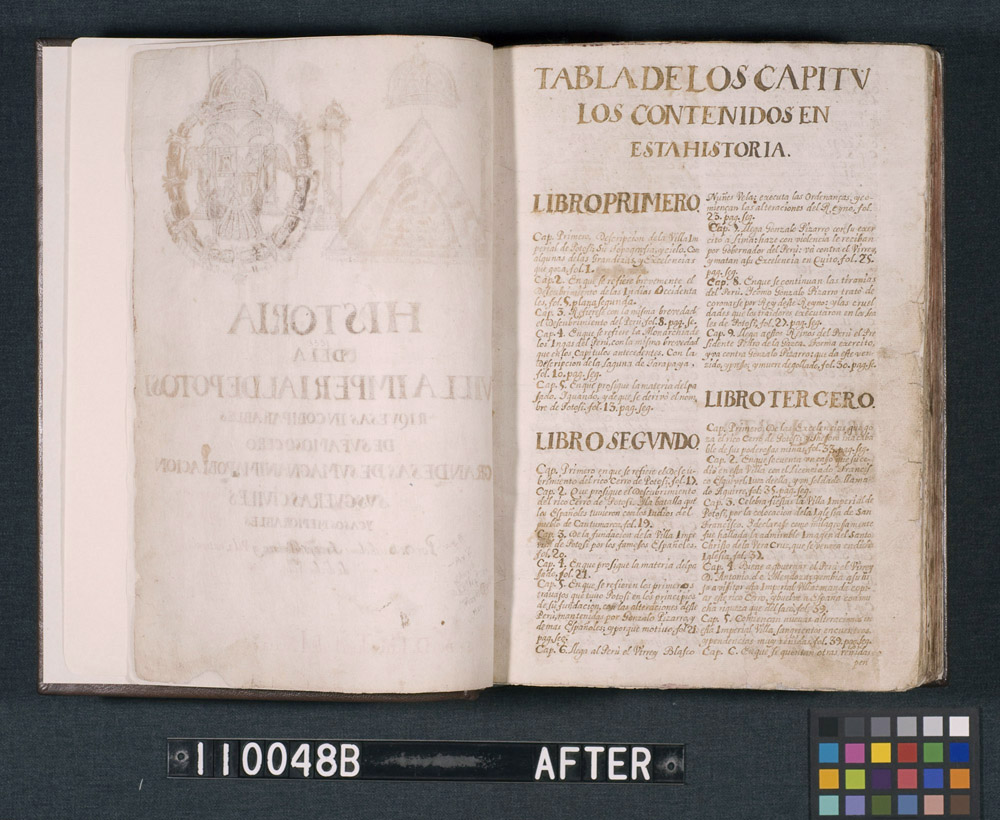

Historia de la villa imperial de Potosí

September 15, 2014 by rness | Comments Off on Historia de la villa imperial de Potosí

Colonel George Earl Church (1835-1910) was commander of a Rhode Island regiment during the Civil War, an engineer, and well known for his explorations into South America. In 1912, the John Hay Library was left his personal library of over 3,500 volumes of economic, historic, geographic, and descriptive studies of South America. One of these volumes, an 18th century manuscript purchased by Church from a Parisian book dealer in 1905, is perhaps the most important item in the collection.

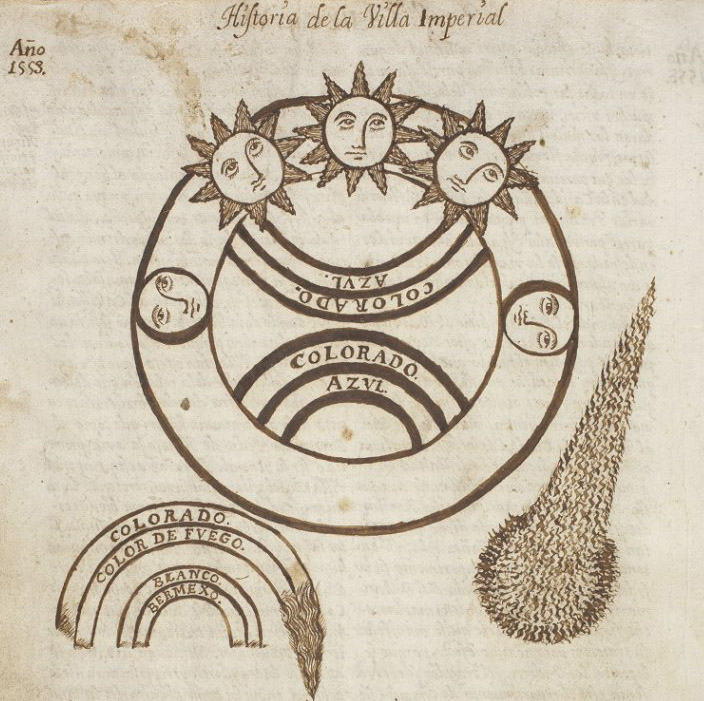

Representation of astronomical phenomena from the mine of Asiento de Porco, Bolivia. January 13, 1553.

The Historia de la villa imperial de Potosí chronicles life in the Bolivian “Imperial City” of Potosí, once the largest city in the New World and home to its most lucrative silver mine.[1. Special Collections of the Brown University Library : A History and Guide.] The manuscript is the “primera parte” of the complete work and records the dramatic social and political unrest of the city, the incomparable riches of its famous hill, greatness of its magnanimous people, its civil wars and memorable cases. Potosí has been vividly described as a “riotous and gaudy civilization” [2. Lewis, Statement concerning the contents of the « Historia de la Villa Imperial de Potosí. Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 1936; pp. 401-404.], “proud and opulent, pious and cruel, torn asunder by dissension.”[3. Phelan, The History of Potosi of Bartolome Arzans y Vela. The Hispanic American Historical Review, Duke University Press, 1967.] Illustrations included in the manuscript portray the metallurgy work of the city, its topographical features, and historic events.

In 1965, in celebration of the bicentennial anniversary of the University, the 1,200 page manuscript was published for the first time in its entirety and in the original Spanish. Now, as the University marks its 250th year, we are pleased to announce that the rare Libro Primero of the Historia de la villa imperial de Potosí has undergone treatment at the New England Document Conservation Center, and a digital version is now available in Brown’s Digital Repository, as part of the Latin American Travelogues collection.

Prior to treatment, the leather binding was degraded and the boards were detached. The pages of the manuscript were dirty and many pages were torn, especially along the edges. The paper was heavily stained and marks in ink and pencil appeared throughout the text. Once the volume was collated and disbound, the pages were washed in a solution of ethanol and filtered water, and sized with gelatin. The fly leaves were deacidified, tears were mended with Japanese kozo paper and wheat starch paste. After digitization, the volume was sewn on linen cords with linen thread, bound in goat leather, and housed in a drop-spine box.

Treatment photos courtesy of NEDCC