Stereoscopy Digitized

Last fall, the Brown University Library acquired a set of 100 stereographs made of Palestine in 1901. Stereographs are made using stereoscopy: a technique that involves creating the illusion of three-dimensional space using two-dimensional imagery. In photography, this means making two images that are just slightly offset from each other, and using a special viewer (a stereopticon) to look at both images at once. The illusion of depth between different spatial elements emerges as our brains attempt to reconcile these two different images into one, creating a (seemingly) three-dimensional scene.

One of the stereographs of Palestine, showing the two offset images that will eventually form the single three-dimensional image.

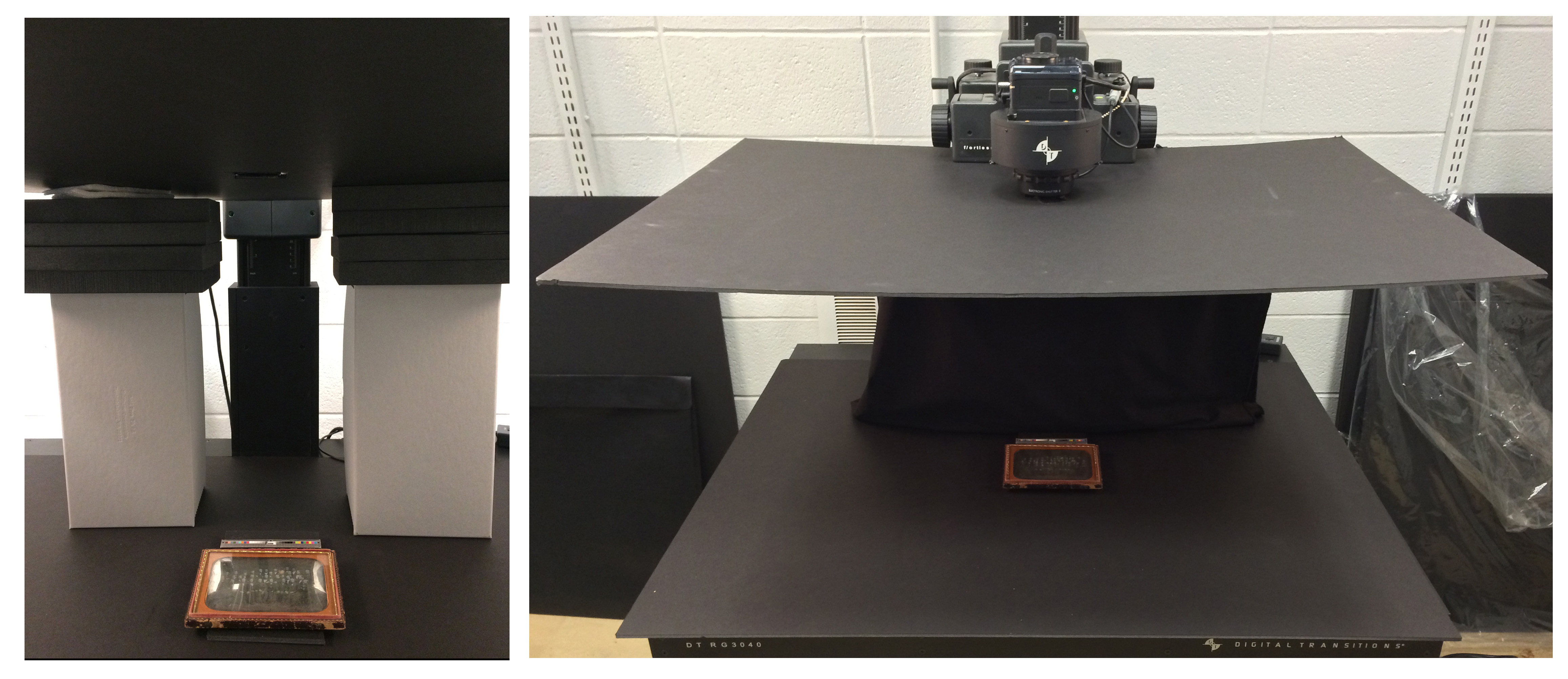

As is the case with most stereographs of this kind, these photographs are albumen prints that have been mounted onto thick card stock. Over time, many of these cards develop a curvature towards the mounted-print side. This makes it very difficult to digitize the images using a flatbed scanner; you can’t get even focus or lighting on a non-flat object, and it’s easy to rip the images or crack the emulsion of the photographs if any attempt is made to flatten the cards. This set of stereographs was no exception, and many of the cards had a distinct curve to them. To account for this, I digitized them using our reprographic camera so I could light them effectively and avoid the need to flatten the object altogether.

The next step was to create a three-dimensional image from each stereograph. There are a number of software applications that enable the user to merge two images from a stereograph into a single image that can be viewed as three dimensional using 3d glasses. I chose 3d Slide Maker, a freeware Macintosh application made by Mike Cook. This software lets the user upload the left and right sides of the stereograph, and then adjust the level of offset on the horizontal and vertical axes. It’s easy to view changes are you make them, so if you have a set of 3-D glasses you can check your work as you edit. This software also allows for additional imaging adjustments to correct any problems that creating the final 3-D image, or anaglyph, has caused in the image quality.

Once each new image was complete and exported, it was added to the collection of images. Each stereograph has three images associated with it: the front of the card; the back of the card (many of these have writing about the scene pictured on the front); and the 3-D anaglyph. If you have 3-D glasses, you can view the image below as a representation of what viewing the stereograph using a stereopticon might be like. You can also click here for an animated gif that shows the offset of the images.

This collection will be displayed at Brown through 100 stereoscopic viewers in Fall 2016, curated by Ariella Azoulay and Issam Nassar, under the title Time Travelers in Palestine – Stereoscopic Journey.

It’s a lovely portrait, and one of the only portraits of him from that time period. The only problem? At some point, the image was retouched to mask out a large area around Mr. Nesbitt’s face – giving this unusual halo effect that proved very distracting. Normally, our archival digitization workflows aim only to capture the originals as accurately as possible, but this was a special case for this particular collection, so we decided that we would keep two copies of the scan that I’d made. We kept one version that included the original retouching, and a new version where I eliminated the halo, and attempted to recreate as best as possible the image underneath. We would add both versions to the Brown Digital Repository, and also wanted to be able to make new prints of the image – printed using archival processes and fine art papers – that we could use for display to protect the original from damage.

It’s a lovely portrait, and one of the only portraits of him from that time period. The only problem? At some point, the image was retouched to mask out a large area around Mr. Nesbitt’s face – giving this unusual halo effect that proved very distracting. Normally, our archival digitization workflows aim only to capture the originals as accurately as possible, but this was a special case for this particular collection, so we decided that we would keep two copies of the scan that I’d made. We kept one version that included the original retouching, and a new version where I eliminated the halo, and attempted to recreate as best as possible the image underneath. We would add both versions to the Brown Digital Repository, and also wanted to be able to make new prints of the image – printed using archival processes and fine art papers – that we could use for display to protect the original from damage.