Streamlining Broadsides

September 5, 2014 by lelgin | Comments Off on Streamlining Broadsides

Over the past year, Digital Production Services has been working on the digitization of one of the Brown University Library’s extensive collections of broadsides. The Rider Broadsides Collection (named for Sidney S. Rider, the Providence bookseller, publisher, and antiquarian from whom the collection was purchased and then subsequently donated to the university) is the largest privately owned collection of materials related to history of Rhode Island. It’s been a great opportunity to see firsthand such historic materials, and the broadsides themselves have been largely straightforward to digitize.

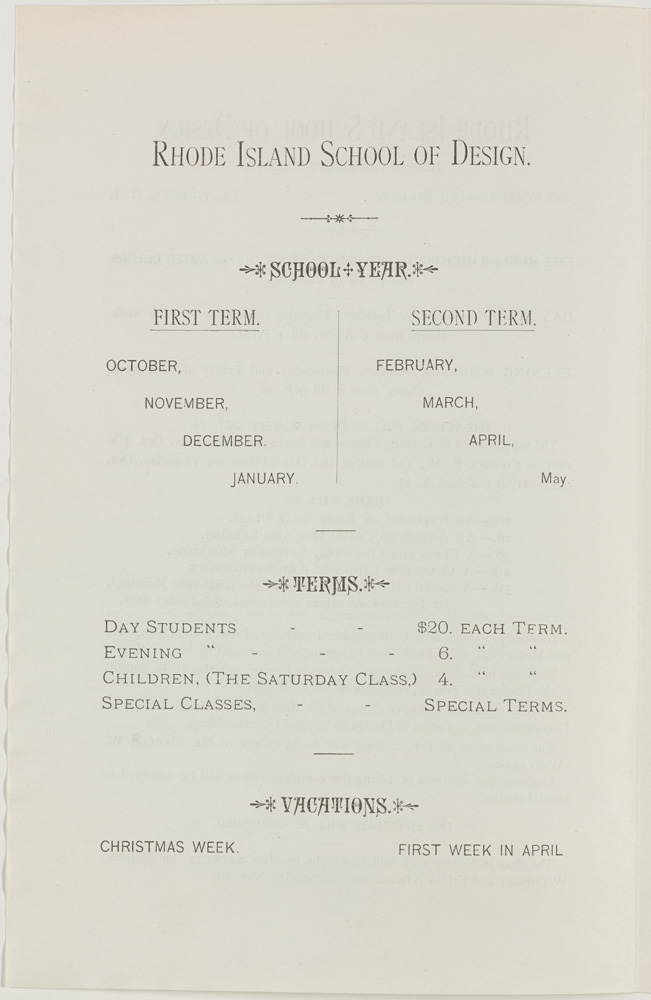

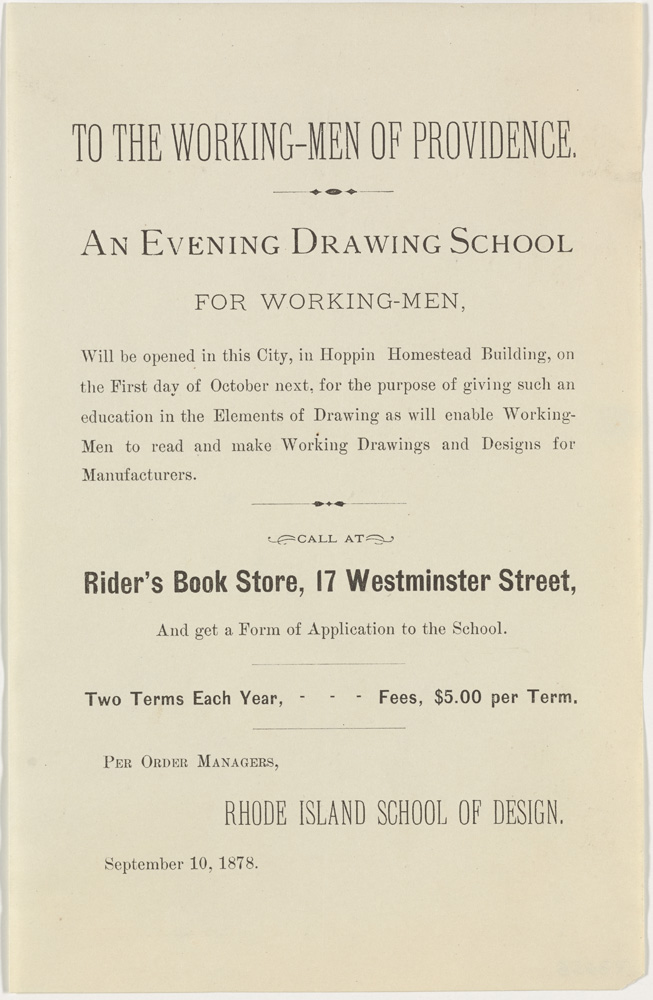

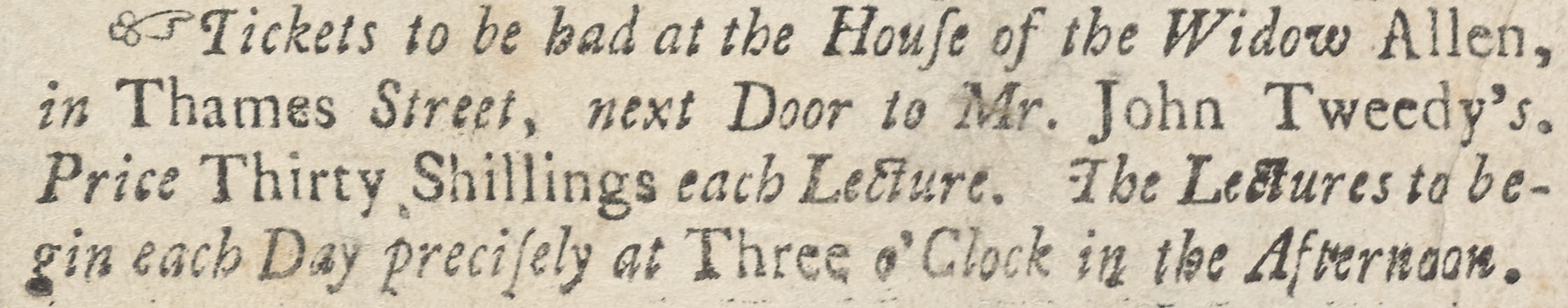

Just one of many historical documents that DPS has digitized as part of the Rider Broadsides collection.

And the ability to digitize these materials efficiently is important when undertaking such a large project; were the materials all fragile, oversize books with foldouts, digitization could easily take years. But the Rider Broadsides have two important qualities that allow for high quality and high speed digitization: they are mostly flat materials, and many of the broadsides are approximately the same size. Books, for instance, with most setups require constant focus adjustments since the distance from the camera to the page changes as one moves through the books. Likewise, materials with size differences require the camera to be raised or lowered (and then refocused) to accommodate these variations and provide the best quality image. The Rider Broadsides, though, allowed us to set the camera height and focus at the beginning of a session, and then digitize a full day’s worth of work without requiring substantive changes in our setup (spot checks for focus and exposure are always made).

However, once the regular size materials had all been digitized, we moved onto the oversize materials, which present more of a challenge. There are just shy of 400 1-Size broadsides, which vary in size from 12″ x 16 ” to 18″ x 24″ (give or take 1/4″). While this may not seem like such a wide range, going from the smaller size to the larger requires us to either reset everything for each shot (including special compensation for vignetting on the larger materials), or to shoot everything as if it were the largest size. The problem with shooting for the largest size object is that we’d be compromising resolution: as the camera moves further from the object, resolution decreases. We had shot all the regular materials at 600 ppi (at full size), so one of our goals is to maintain as much resolution as possible. So we had to devise an approach to digitizing these materials that would maintain the efficiency as well as the quality that we had achieved with the regular-sized broadsides.

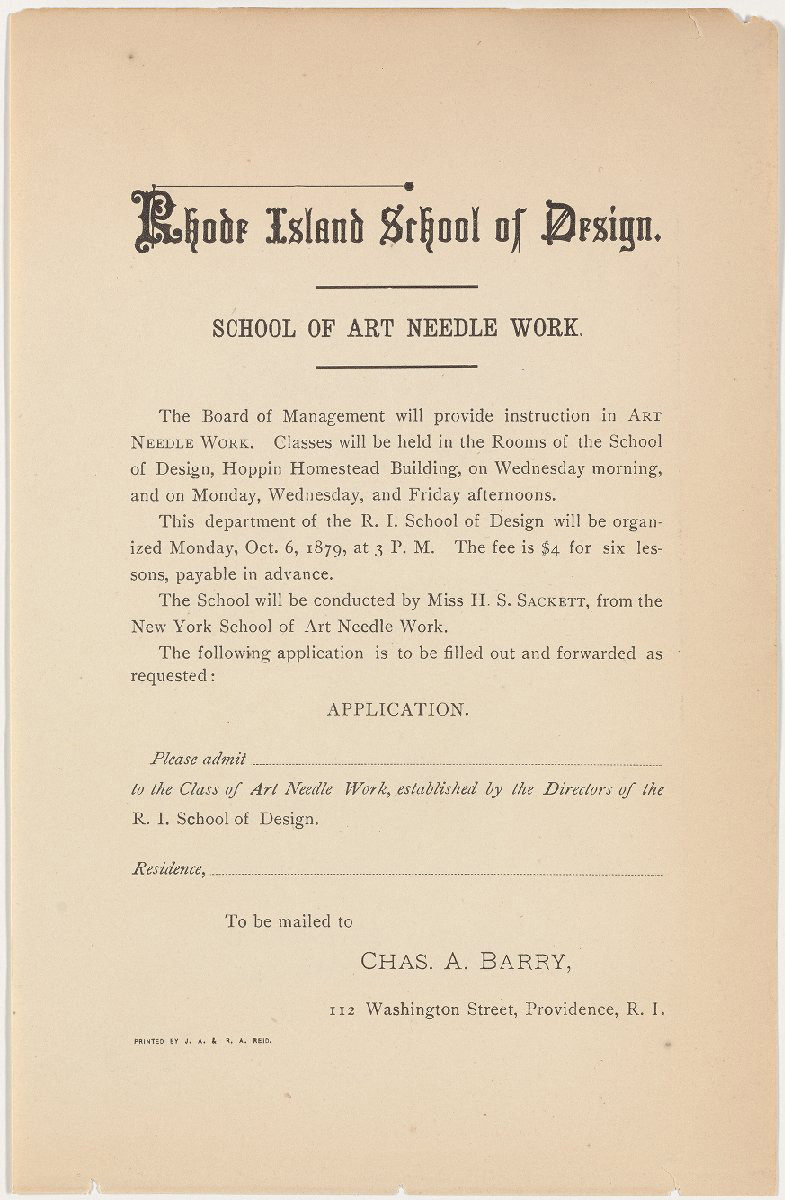

Each of the four groups of broadsides, separated and labeled by size and camera settings.

The answer was to separate out the broadsides by size, and create a specific and easy-to-replicate camera setup for each size range. After going through every broadside, I came up with four size categories: 12 x 16, 14 x 19, 16 x 21, and 18 x 24 (all in inches). All the broadsides fit into one of these size ranges, which allow us to maximize resolution for each size. With a fixed set of size ranges, I went about determining the camera setups. Using just a tape measure and camera target, I plotted where on the camera platform a specific size would fall. I them focused the camera on the target, to see precisely where the camera needed to be to cover the entire image area while in focus. I noted the maximum size of an object for that image area, the resolution that could be achieved, and the height that the camera required (this number is taken from the mounted rail on the camera platform). I made labels for each set of broadsides, which I had separated onto different book trucks.

I also made tape labels for each size range that I affixed to the camera rail. This way, regardless of the person working in the camera room that day, and regardless of which group of broadsides they were working on, all the photographer needs to do is check the label on the stack of broadsides to determine the image size, find the corresponding label on the camera rail, move the camera to level with the label, focus, and shoot. We have digitized hundreds of broadsides so far, and this has turned out to be useful not just for effective digitization, but also for easier retrieval of paged materials.

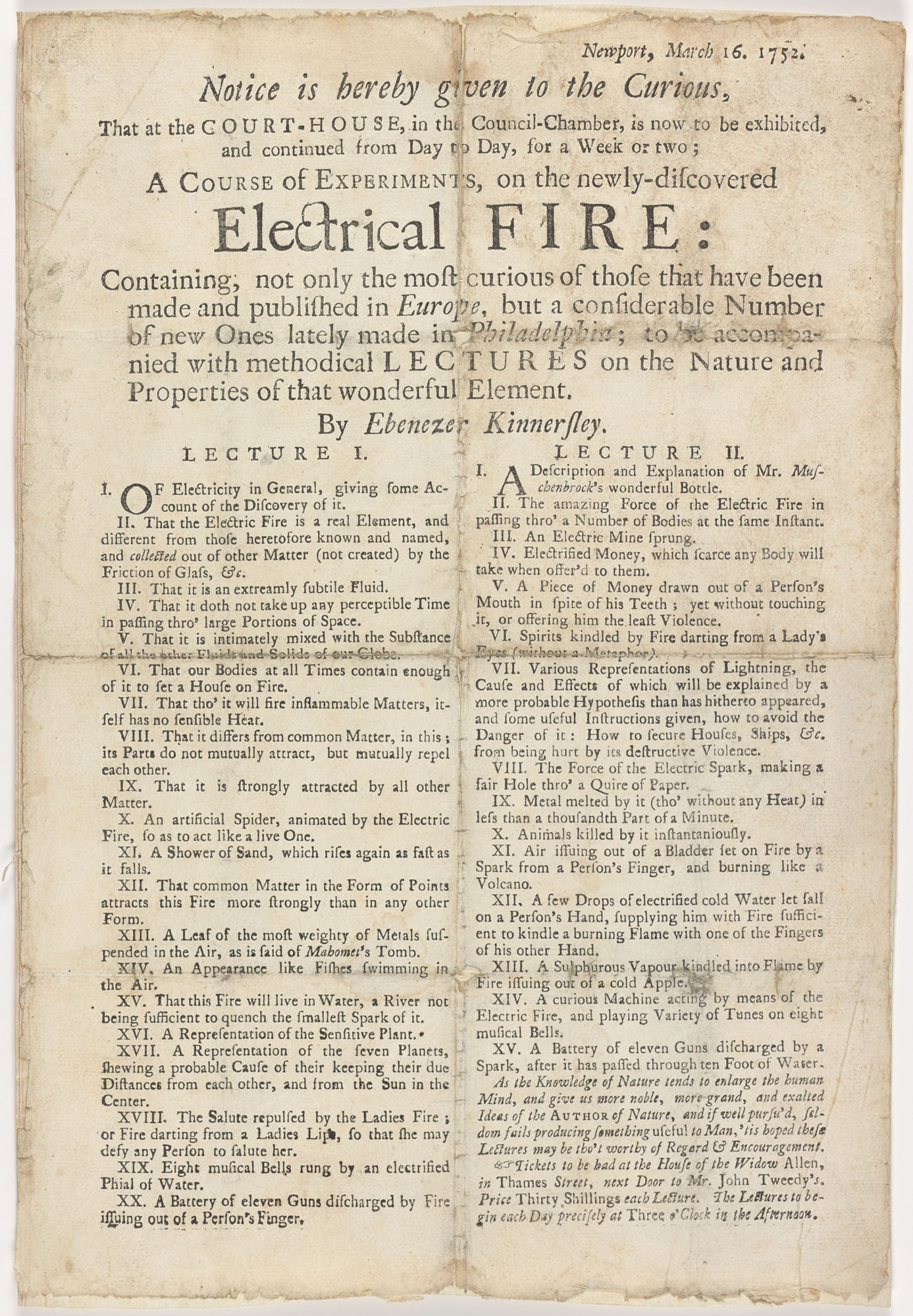

Details of signage and camera rail markings.