Napoleon’s Death Mask

January 23, 2013 by lelgin | 4 Comments

While the bulk of my work involves the digitization of two-dimensional documents, or straightforward photographs of pages from books, I also photograph other types of items – like the 360 degree photography, and the interiors that I have posted about. Every once in a while, I get more unusual requests. Since I am usually the person who handles three-dimensional items, I get to photograph some of the most interesting – and unexpected – items from our collections.

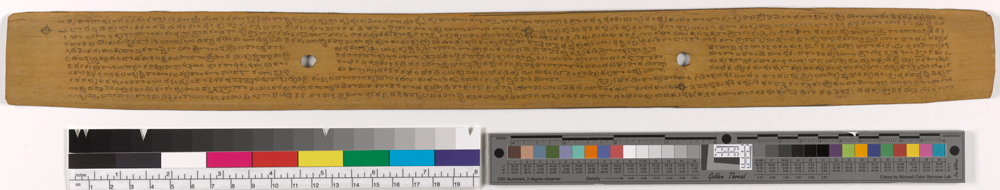

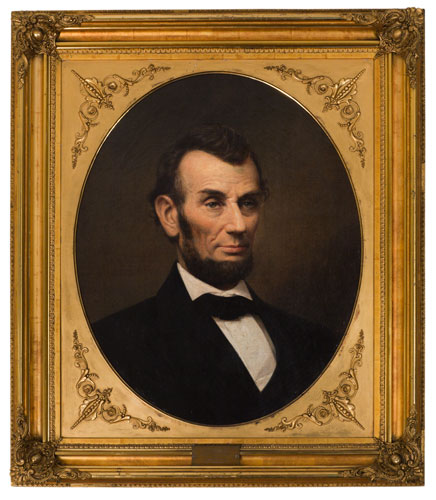

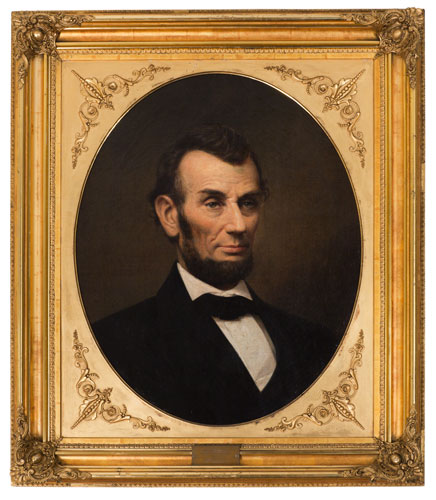

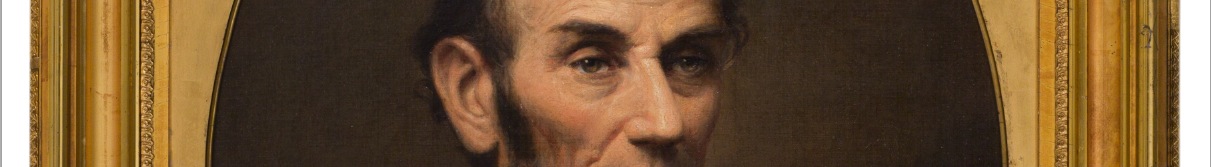

Two years before this shoot, I actually photographed a portrait of Napoleon; an oil painting by Vernet in a gold-colored frame with the familiar bee (a symbol of immortality and resurrection) carved onto the front. It’s a part of the William Henry Hoffman Collection on Napoleon I and it’s absolutely stunning. Actually, the entire collection (of approximately 600 items) is fascinating, so I was excited when I was called over to look at an object that needed digitization. I was a little surprised to find it was not exactly a portrait of Napoleon; it was a plaster cast of his death mask. The request had come internally; we have a series of talks on our Special Collections at Brown, and this image was to help publicize and showcase a talk on the mask, given by Peter Harrington, curator of the Anne S.K. Brown Military Collection.

I had to bring it back to my studio at DPS to photograph, as I needed better light than I could get in the room the mask is stored in. I set everything up before bringing the mask out of its box; I was using hot lights, and the less exposure the mask has to the heat and drying nature of the lights, the better. Using a stack of books about the same size and shape of the mask, I set up foam to cushion it on a low table, set up lights equidistant and at the same angle to the object, and utilized the horizontal arm of our tripod so that I could shoot straight down onto the object. I used a color checker card to make sure that my white balance and exposure was correct, I tripled-checked the depth of field and focus, and then was ready to go.

As is often the case when dealing with unique objects, the setup took much longer than the actual photography. I replaced the books very carefully with the mask, took approximately 10 shots at slightly different exposures and focuses at three different angles. I ended up with a high resolution photograph of the death mask, and a great response when people asked me what I was bringing around the library in a box.