Festival Book as Political Propaganda: The Long Celebrations for a Marriage in Naples

Ruth Lo

L’ossequio tributario della fedelissima Città di Napoli, per le dimostranze giulive nei Regii Sponsali del Cattolico, ed Invittissimo Monarca Carlo Secondo colla Serenissima Principessa Maria Anna di Neoburgo Palatina del Reno, sotto i felicissimi auspicii dell’Eccellentissimo Signor D. Francesco di Benavides, Conte di S. Stefano, Vicerè, e Capitan Generale nel Regno di Napoli. Ragguaglio Historico, Descritto da Domenico Antonio Parrino Napolitano. Naples, Domenico Antonio Parrino, 1690.

The Respectful Tribute of the most faithful City of Naples, by the joyful celebrations for the Royal Marriage of Charles II of Spain and Maria Anna of the Palatinate-Neuburg.

The careful documentation of royal marriages produced one of the most popular types of festival books. Detailed descriptions and illustrations recorded myriad events that commemorated the joining of great political and economic powers and, most importantly, the prospect of new successors to the ruling lineages. Weddings were thus major milestones in the lives of princely dynasties, and their celebrations heralded renewed optimism for prosperity and security in their political realms. Cities – often in competition with one another – organized lavish and protracted festivities that provided evidence of their respect and allegiance to royal authority.

The production of festival books memorialized the city’s extraordinary efforts by further solidifying its ties to the sovereign in a visible and enduring manner. Recording the celebrations in text and with illustrations provided a lasting demonstration of the city’s loyalty to the royal couple, long after the events had passed. Though many festival books, by their very titles, claimed to present full and truthful accounts of events, their contents should not be taken at face value. Festival books were in fact formidable instruments of political propaganda through their authors’ careful editing of the events to further political agendas. While the veracity of these accounts cannot always be ascertained, festival books nonetheless offer important clues to the political and cultural milieux that led to the organization of celebrations and the recording of them.

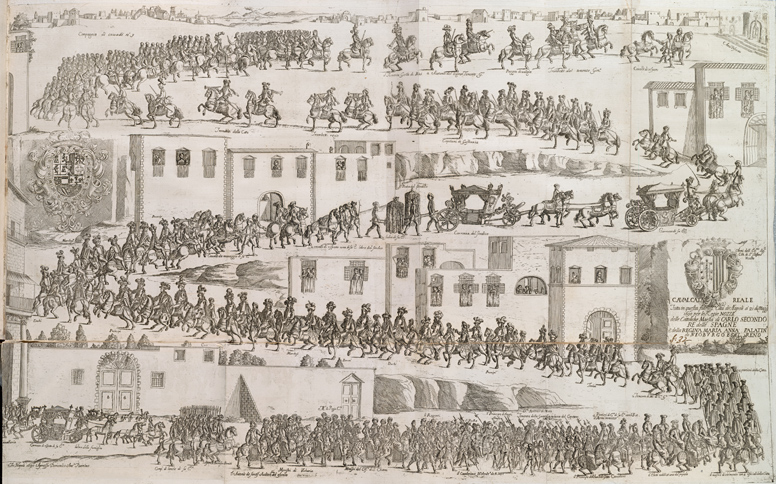

The festival book documenting the events put on by the city of Naples for the wedding of King Charles II of Spain and Princess Maria Anna of Palatinate-Neuburg in 1690 provides a good example of the political significance of festivals. Presenting an “ossequio tributario,” or most respectful tribute, to the royal couple from the Kingdom of Naples, the Neapolitan author Domenico Antonio Parrino offered a detailed history (“ragguaglio historico”) of the civic festivities that spanned an eight-month period. While other Italian cities connected to the Spanish monarchy – such as Rome, Zagarolo, Palermo, and Florence – also celebrated this royal union, none of them sponsored festivities that were as elaborate and lengthy as those held in Naples. The Kingdom organized a plethora of events despite the absence of the royal couple during the entire eight-month period.

The marriage of Charles II and Maria Anna presented a fitting opportunity for Naples to restore its status within the Spanish Empire. Through the planning of extensive celebrations, the Kingdom hoped to redeem its reputation marred by the Masaniello Revolt against the Spanish Habsburg monarchy in 1647. This local uprising protested Spain’s heavy taxation, and it severely damaged Neapolitan-Spanish relations. As such, the festivities in 1690 served as a proclamation of unfaltering devotion to the King and a means of re-establishing trust between Naples and Spain. The accompanying festival book functioned as a reassuring written testimony of Naples’ commitment to the Spanish monarchy.

To regain the trust of Spain, the Kingdom of Naples organized ostentatious celebrations despite the economic difficulties it was facing at this time. Food and other supply shortages swept across the Kingdom as Spain drained its resources by engaging in several lengthy and costly wars. The past and present troubles of Naples at the end of the seventeenth century underscored the tremendous efforts it invested in placating the monarchy. For example, despite the shortage of wax, the city insisted on illuminating the entire city on the nights of October 4 and 5 of 1689 following the August 28 proxy wedding of Maria Anna in Austria. In order to do so, torches were constructed with exorbitant replacements made of wood and copper and lit with oil (Moli Frigola, 122).

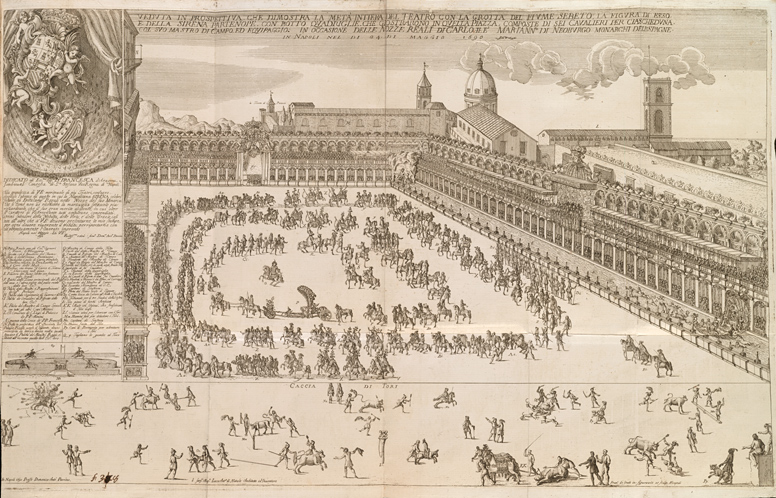

Parrino’s account certainly did not mention the Kingdom’s inglorious recent history and financial woes; instead, he chose to focus on Naples’ extensive transformations of the urban fabric in celebration of the royal wedding and the possibility of a new male heir. Among the city’s extravagant endeavors was the construction of an amphitheater in the shape of a parallelogram painted to resemble fancy marble. Several lavish events were staged in the amphitheater in May of 1690 to coincide with the new Queen’s arrival in Ferrol, Spain, and her entrance to Madrid. These included horse formations by quadrilles, jousts, and bullfights – the latter was a compulsory element of any Spanish festival (Sánchez).

The most impressive feature, however, was a grotto and a ‘simulacrum’ of the Sebeto River spanning five hundred feet along one side of the amphitheater. Emulating the water designs at the gardens of Villa d’Este in Tivoli (Moli Frigola, 122), a long channel was filled with spring water and lined with ninety fountains on its banks. Inside a grotto at one end, a giant statue of the Sebeto River looked affectionately at the Siren Parthenope. The simulacrum of the Sebeto River was in fact a Neapolitan allegory for the love of Charles II and Maria Anna.

The incorporation of this sophisticated design element exalting Love was reflective of the increasingly desperate need to sire a successor to the Spanish throne. Marie Louise d’Orléans, the first wife of Charles II, died childless in February 1689. The monarchy launched an expeditious search for a replacement queen in hopes of producing a male heir to assure dynastic continuity in Spain. The Empire was already experiencing political and economic decline under the weak reign of Charles II, and the prospect of a succession crisis was a risk not only to the Spanish Empire but the larger balance of power among European monarchies.

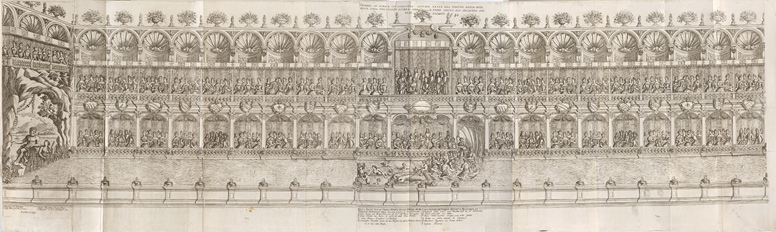

Accordingly, the wedding celebrations for Charles II and Maria Anna in Naples reflected the desire and urgency that the Empire had conferred on the production of an heir. The simulacrum of the Sebeto River was thus a main feature of the festivities in Naples, and its prominence was replicated in the attentive details documented in Parrino’s festival book. Visual representations of the simulacrum – prints produced by the engraver Francesco de Grado – appeared twice in the book: once in a totalizing perspectival view of the amphitheater (Figure 1), and another in a seven-part foldout of an elevation close-up of the river and the grotto in front of viewing boxes (Figure 2).

Based on Boccaccio’s legend of the amorous affair between Sebeto and Parthenope, the simulacrum was conceived by the military architect Luca Antonio di Natale, who also designed the amphitheater. Natale may have based his design of the Sebeto statue in the grotto on an earlier fountain created in Naples by Cosimo Fanzago in 1635. The spectacular performance of a shell-shaped water carriage, rising up to thirty-palms tall, navigating down the simulacrum of the Sebeto River took place on May 22 in celebration of the royal marriage. The vessel carried characters representing Amore (Love), Himeneo (Hymen, the god of marriage ceremonies), Lucina (the goddess of childbirth), and the Muses, and was led by two dolphins, twelve mermaids and six tritons. As can be seen in de Grado’s illustration, the water carriage passed directly in front of the boxes reserved for Spanish and Neapolitan nobilities, including the Viceroy D. Francesco di Benavides, the financial patron of the celebrations, and the Viceregina.

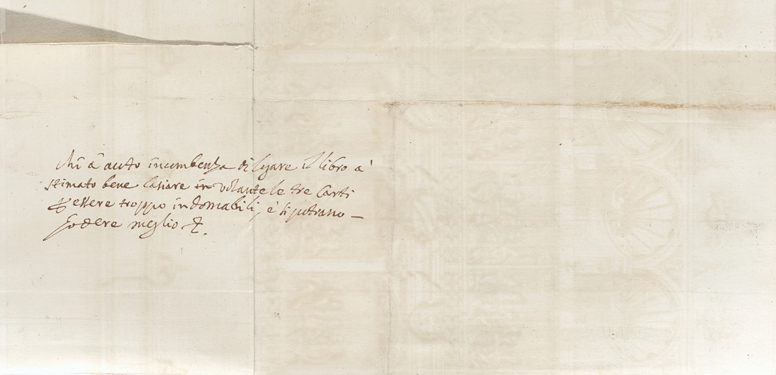

De Grado’s print of this ‘nobilissima invenzione’ presented meticulous details of the spectacle that perpetuated the myth of an affluent Kingdom and Empire. This disproportionately large print offered very close views of the boxes lavishly adorned with ribbons, tapestries, flowers, and maritime motifs. In the middle of the print, below the box of the Viceroy and Viceregina, de Grado illustrated the distribution of refreshments to the aristocratic ladies, which Parrino also described in his written account. The extraordinary size of this print far exceeded the dimensions of the other two illustrations – of the procession (Figure 3) and the amphitheater – in this book. In fact, the bookbinder noted on the back of the Sebeto River print that de Grado’s very large illustrations would have been better enjoyed if they were left unbound (Figure 4). The minute details, rendered in both visual and textual terms, attested to the wealth and generosity of the Kingdom of Naples. By proxy of its relationship to Spain, they also symbolized the prosperity of the Empire.

This was, at least, what the Kingdom wanted its people and the Spanish monarchy to believe. The excessive festivities were staged to promote civic solidarity and allegiance, and Parrino’s festival book further projected this self-made image of Naples. Yet, the format and content of the festival book also revealed the Kingdom’s insecurities about its relations with Spain, which it hoped to fortify with overt displays of adulation toward the royal couple. The elaborate staging of the Sebeto River spectacle was indicative of the preoccupation with securing a legitimate dynastic successor, which would indeed have a severe impact on European politics following the death of Charles II. In the end, the adoration of the Neapolitans could not save the Spanish Habsburgs. The death of Charles II in 1700 would prompt the War of Spanish Succession in 1701, and it continued until 1714 when Philip V was finally recognized as the first Bourbon king of Spain.

Translation of key in Figure 1

The City of Naples, a Vice-kingdom of Spain, constructed a grand amphitheatre with a gigantic simulacrum of the Sebeto River as part of an eight-month long celebration, including spectacles such as parades, jousting, and bullfights, of the marriage of Charles II of Spain and Maria Anna of the Palatinate-Neuburg. The etching collapses several events that took place in that space on different days, describing them in the key at the upper left, which reads:

A. |

Royal box for the Viceroy & Viceregina |

V. |

Entrance to the Theater, across from Via Toledo |

B. |

Grotto with the simulacrum of the River Sebeto & the mermaid Parthenope |

X. |

Quadrille of six Knights |

C. |

Shell-shaped triumphal carriage with Hymen, Love, the goddess Lucina, & a chorus of Muses |

Y. |

Two assistants of the Quadrille |

D. |

Dolphins pulling the carriage & Tritons playing in the water |

Z. |

Twelve footmen of the Quadrille |

E. |

The Sebeto River with fountains on the banks |

AA. |

Six cavalli di rispetto belonging to the six Knights |

F. |

Boxes for the Queen’s ladies |

BB. |

2 Trumpeters, 2 Drummers, 2 pipe players, & a military wagon |

G. |

Boxes for the Ministers of the Prince |

CC. |

Twenty Footmen of the Field Master |

H. |

Boxes for the Secretaries of War & Justice |

DD. |

His Excellency’s German Guards |

I. |

Boxes for the servants |

EE. |

Captain of Justice |

K. |

Box of the Field Master |

FF. |

Entrance to the Theater across from the Giant |

L. |

The Convent of San Luigi of the Palace of the Minim fathers |

GG. |

Lists for the Game of Running at the Head & the Ring |

M. |

The Franciscan Convent of the Cross |

HH. |

Tribunes for the 3 Judges of the Joust |

N. |

Perspective profile of Royal Palace façade |

II. |

Bull full of fireworks |

O. |

Field Master |

KK. |

Mule with slaves who drag the slain Bull |

P. |

The Field Master’s carriage |

LL. |

Live monkey to taunt the Bulls |

Q. |

The Field Master’s cavalli di rispetto |

MM. |

Fake men to fool the Bulls |

R. |

Two assistants to the Field Master |

NN. |

Captains of Justice |

S. |

The Field Master’s trumpeters |

OO |

Man wounded by the Bull |

T. |

Two porters of the Field Master |

PP. |

Hunting dogs to bite the Bulls |

|

|

QQ. |

They cut the legs of the Bull |

Bibliography

Comune di Napoli. “The Siren Parthenope.” Mythical and Legendary Origins of the City. 5 May 2010.

Comune di Napoli. “The Sebeto River.” Mythical and Legendary Origins of the City. 5 May 2010.

Kamen, Henry. Spain in the Later Seventeenth Century, 1665-1700. London and New York: Longman, 1980.

Moli Frigola, Montserrat. “Fiesta Publica e Himeneo. La Boda de Carlos II con Mariana de Neoburgo en las Cortes Españolas de Italia.” Norba-Arte, Vol. 9, 1989. 111-144.

Nada, John. Carlos the Bewitched: The Last Spanish Hapbsurg, 1661-1700. London: Jonathan Cape, 1962.

Sánchez, David. “Festivals in Spain.” British Library. 5 May 2010.

Storrs, Christopher. The Resilience of the Spanish Monarchy, 1665-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Watanabe-O’Kelly, Helen. “The Early Modern Festival Book: Function and Form.” ‘Europa Triumphans’: Court and Civic Festivals in Early Modern Europe. Vol. I. Edited by J.R. Mulryne, Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly and Margaret Shewring. Aldershot, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004. 3-18.