The Compression of Time and Space in Festival Book Illustrations

Ruth Lo

The ephemeral nature of festivals often engendered the printing of detailed accounts to extend the memory of the celebrations beyond their actual lifespan. The staging of large-scale civic events required patrons to invest an inordinate amount of money and effort, and the printing of festival books assured that their achievements were officially recognized by their contemporaries and also recorded for posterity. Since many royal celebrations were multi-day affairs, authors of festival books had to decide how to manage the chronicling of events that took place over a period of time. This was especially complex for visual representations of events in festival books, which often had to deal with the compression of space in addition to time.

Methods of recording the passage of time varied widely in 16th to 18th century festival books. While some books were dedicated to describing an event that occurred on one particular day, others detailed celebrations that spanned several months. A number of them contained only textual information, but many had illustrations that offered totalizing views of a conflation of events. In the latter cases, the texts often provided clarification on the dates and times, offering the reader a better comprehension of the sequence of events. Some festival books maximized the book format by utilizing the act of turning a page to convey movement and the passage of time. Corteges and processions often adapted well to this composition by using the book’s structure to enhance the understanding of spatial transgression and temporality.

Depiction of Royal Cavalcades

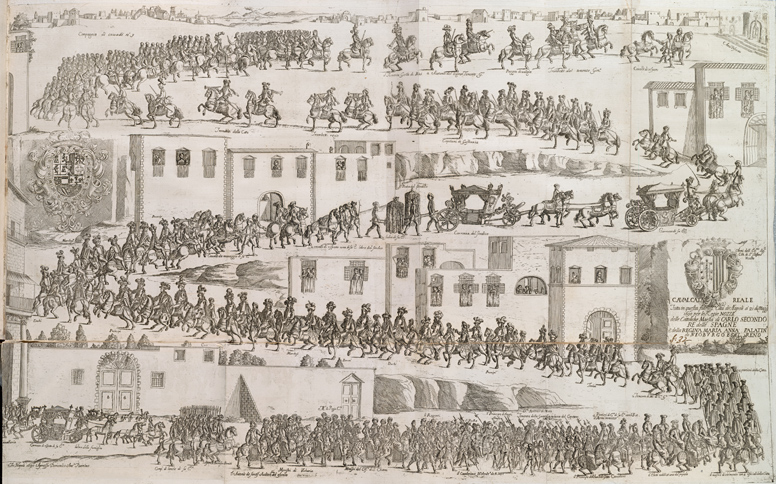

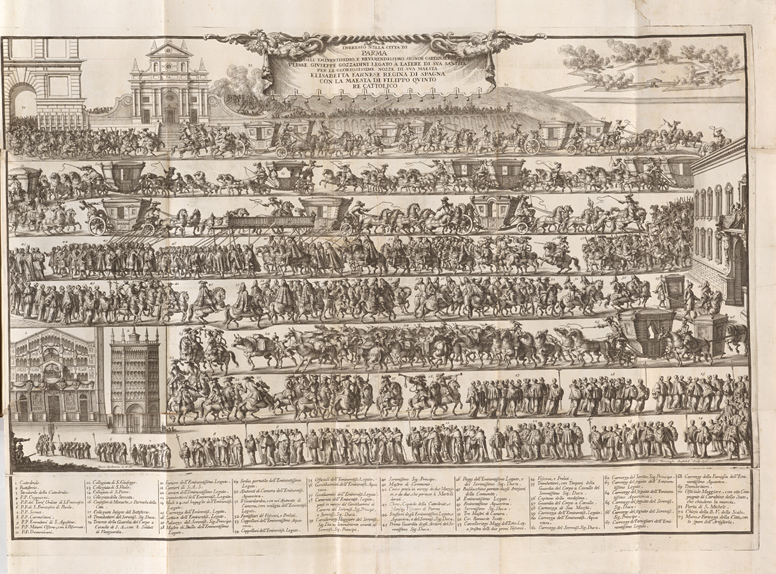

An alternate way of conveying the journey across space was to illustrate these marches on one single sheet, which relied on the artist’s rendering to guide the reader’s eyes to imagine movement and the passage of time. The etchings in L’ossequio tributario della fedelissima Città di Napoli per le dimostrazione giulive nei Regii Sponsali di Carlo II e Maria Anna by Francesco de Grado (Figure 1) and Ragguaglio delle Nozze delle Maestà Filippo Quinto e di Elisabetta Farnese by Teodoro Vercruysse (Figure 2) are two examples that demonstrate typical representations of royal cavalcades on folio sheets that were bound and folded into festival books. Both plates use a boustrophedonic composition (alternating directions tier by tier) to show the corteges in their entirety coiling back and forth several times on the page to indicate their order as they traversed the cities.

The totalizing views of these etchings place the reader in a privileged position that no attendee at the time would have been able to witness. The festival participants could not have seen the whole procession in one single view; this was not possible even for the ladies peering out of windows along the parade routes. The spectator was compelled to choose a fixed observation point, as Louis Marin writes, “He cannot theoretically dominate time in its unfolding in space. It is in succession that he comes to know the episodes” (Marin, 227).

The reader’s omniscient view, on the other hand, becomes a visual summary of the events. While the texts in the festival books elaborate upon the details of the corteges—often including such things as a list of names, the ordering of the participants, and the costumes and adornments—the collapse of time and space in the plates offers immediacy in the reader’s comprehension of the events. The clear labeling of the processional members, with their titles along the parade route or with a legend, further aids in this process. The texts explaining these illustrations provide crucial but supplemental information, and they do not disrupt the reader’s overall understanding of the spatio-temporal relationship.

The sense of movement through space is conveyed by the orderly but dynamic depiction of the corteges. The print by Vercruysse illustrating the procession for the proxy wedding of Elizabeth Farnese in Parma is an exceptional example of this (Figure 2). While the image itself is static, its content demonstrates the tremendous vigor and liveliness of the event, thus contributing to the reader’s understanding of the rite of passage that this ritual movement symbolizes. Upon first viewing, the page is neatly composed of cortege participants, horses, and carriages organized linearly in rows spanning the width of the folio. The systematic arrangement is, however, enlivened by the vibrancy in the depiction of the characters. Horsemen wielding their whips with urgency and authority are shown together with trumpeters playing their instruments enthusiastically. The galloping horses and the luggage-carrying mules are also depicted with an abundance of energy. The vivacity of the cortege participants activates the inert nature of the medium, and it thereby allows the reading of the festival book to surpass even the experience of seeing the event in person, which would by its nature necessitate a fixed viewing position in which the viewer would encounter the participants one by one as they passed by.

The one-directionality of the corteges in both Vercruysse and de Grado’s prints also helps to construct the reader’s understanding of the spatio-temporal relationship. The one-way journey “signifies irreversibility and focuses on a cathartic final point” (Falassi, 221), which guides the reader’s eyes through the boustrophedonic compositions. In Vercruysse’s depiction of the proxy wedding in Parma, the courtiers are seen as entering the city through the Porta di S. Michele on the top left corner and arriving finally at the richly decorated Cathedral of Parma and the Baptistery on the bottom left corner of the print. The inclusion of certain architectural structures along the route, such as the Chiesa della Beata Vergine della Scala, the city walls, and the Ducal palace, provide context to the cavalcade. These elements suggest that the procession’s participants are in fact moving along a given route within the urban fabric. In de Grado’s perspectival view, the cortege is organized by a three-dimensional but generic and fictional urban context. As opposed to Vercruysse’s print, de Grado’s cavalcade marches into Naples from the bottom left and arrives at the church on the top right.

Depiction of Staged Spectacles

The compression of time and space was often employed in festival book prints to illustrate the staging of large-scale spectacles. Since it was costly to commission artistic renderings of festivals, many engravers, etchers, and illustrators produced a single work showing a variety of events that may have occurred over a period of time. In this case, the reader must rely on the text in the festival book for a clear understanding of their sequence.

The festivities in Naples for the wedding of King Charles II of Spain and Princess Maria Anna of Palatinate-Neuburg presented an especially interesting case in addressing the passage of time. The festival book published by the Neapolitan Domenico Antonio Parrino carefully documented this exceptionally long celebration, which consisted of many spectacles that occurred in short periods between October 1689 and May 1690. These moments of festivity commemorated the major proceedings in the marriage, but they mainly followed Maria Anna’s journey to Spain. The festival book tracked the celebrations for five stages of this process: 1) courtship, 2) proxy wedding in Neuburg, 3) embarkation in Flushing, 4) wedding at Valladolid, Spain, and 5) entry to Madrid.

Though the announcement of the King’s selection of Maria Anna as his second wife was not celebrated, the fact was recorded at the very beginning of the festival book as the commencement of the ‘courtship.’ However, the author kept the descriptions of this moment to a minimum, while some festival books, like the one for the marriage of King Philip V of Spain and Princess Elizabeth Farnese of Parma in 1714, elaborated on the details of the courtship such as the process of selection and who was involved in the King’s decision. Typical of festival books for royal weddings, Parrino’s volume also briefly mentioned the lament for the death of the first queen, Marie Louise d’Orléans (1662-1689).

The proxy wedding of Maria Anna took place in Neuburg on August 28, 1689, and Naples swiftly launched its civic festivities on October 3. Among the ephemeral structures erected throughout the city was a large amphitheater, designed by the military engineer Luca Antonio di Natale, which hosted many of the events celebrating this marriage. In the following two-week period, the city staged a variety of festivities that included a Te Deum, illumination of the city for two nights, a masquerade of knights, and a play.

Following the embarkation of Maria Anna from Flushing in January 1690, Naples celebrated the event on February 7, the last day of Carnival, with elaborate festivities in the amphitheater. Viceroy D. Francesco di Benavides, who financed the city’s celebrations, ordered a variety of events including another Te Deum, ballo di torcia (fire dance), a bull hunt, tournaments, and other games. Parrino recorded the day’s events with plenty of details, including the names of the nobles in attendance and the participants in the tournaments. Maria Anna’s arrival in Ferrol, Spain on March 27 was, however, not recorded in Parrino’s festival book although the event was celebrated in Naples with a gun salute fired from the castles, forts, and anchored ships (Moli Frigola, 125). Parrino’s omission was perhaps due to the simplicity and short duration of this particular celebration.

After Maria Anna’s wedding to Charles II in Valladolid, Spain on May 4, Naples commenced a series of elaborate festivities to celebrate this long-awaited moment. These began with a royal cavalcade on May 21, which was memorialized in de Grado’s first print (Figure 1). On May 22, the biggest spectacle was staged in the amphitheater: a triumphal water carriage sailed down a simulacrum of the Sebeto River as an allegory for the love between the royal couple. This was followed by a bullfight that lasted well into the evening hours when Naples illuminated the theater and the entire city. Finally, Parrino described a tournament dedicated to the Viceregina on May 24 that coincided with the entry of Charles II and his queen into Madrid. Elaborate quadrille formations, jousts, and other games were staged in the amphitheater to entertain the Neapolitan audience. Some, but not all, of these events can be seen in the illustration.

De Grado’s second print in L’ossequio tributario presents an efficient spatio-temporal collapse that conflated this series of events. He dated the spectacles to 24 May 1690, which he labeled at the top of the print. However, the author Domenico Antonio Parrino’s text revealed that these events actually took place on different days. De Grado portrays the two major events – the large quadrille formation and the water carriage show – within the arena of the amphitheater. Along the bottom of the folio, separate from the perspectival view of the amphitheater, de Grado illustrates a series of prominent moments in a bullfight. It would have been impossible for the orderly quadrille and the chaotic bullfight to have occurred simultaneously within the amphitheater.

When viewing de Grado’s print, the reader may suspect that the events he depicted may not have all occurred simultaneously. However, without consulting Parrino’s text, it would not be possible to understand that these events in fact took place on different days. The artistic rendering presents an interpretation of the festivities that offers only the highlights of the celebrations. Because of the necessity to collapse time and space for the sake of being comprehensive, the illustration does not claim verisimilitude to the actual spatio-temporal relationship of the events as they had occurred in Naples.

Festival book illustrations often provide syntheses of the detailed accounts and of the events themselves through the compression of time and space. While the texts expand upon the festivities by meticulously describing them, the illustrations are visual summaries that imbricate specific moments and features of the celebrations. The visual appeal of festival book prints is achieved partially through the artists’ mastery of condensing information that emphasize major milestones within the course of the celebrations. The collapse of time and space in these prints thus amplify for the festival book reader the experience of (re)visiting these events.

Bibliography

Armstrong, Edward. Elizabeth Farnese, “The Termagant of Spain.” London and New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1892.

Kamen, Henry. Philip V of Spain: The King Who Reigned Twice. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001.

Kamen, Henry. Spain in the Later Seventeenth Century, 1665-1700. London and New York: Longman, 1980.

Lynch, John. Bourbon Spain, 1700-1808. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1989.

Marin, Louis. “Notes on a Semiotic Approach to Parade, Cortege, and Procession.” Time out of Time, Essays on the Festival. Edited by Alessandro Falassi. Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 1987. 220-228.

Moli Frigola, Montserrat. “Fiesta Publica e Himeneo. La Boda de Carlos II con Mariana de Neoburgo en las Cortes Españolas de Italia.” Norba-Arte, Vol. 9, 1989. 111-144.

Nada, John. Carlos the Bewitched: The Last Spanish Hapbsurg, 1661-1700. London: Jonathan Cape, 1962.

Pollock, Martha. Italian and Spanish Books: Fifteenth through Nineteenth Centuries, Volume IV. The Mark J. Millard Architectural Collection. Washington, D.C.: The National Gallery of Art, 2000. 340-344.

Storrs, Christopher. The Resilience of the Spanish Monarchy, 1665-1700. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Watanabe-O’Kelly, Helen. “The Early Modern Festival Book: Function and Form.” ‘Europa Triumphans’: Court and Civic Festivals in Early Modern Europe. Vol. I. Edited by J.R. Mulryne, Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly and Margaret Shewring. Aldershot, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2004. 3-18.