Fireworks

Kristen Oehlrich

The birthplace of fireworks is generally recognized to be China during the Sung dynasty (960-1279), although pyrotechny was also practiced in India during that period. It is unclear when fireworks first appeared in Europe, although it is believed that this occurred during the Middle Ages either through traveling missionaries or through the crusades. By the fourteenth century, however, fireworks were seen frequently in Italy. From here, over the next two centuries, they spread throughout Europe, reaching an unprecedented popularity in the sixteenth century. There are a limited number of visual references to fireworks in the fourteenth and fifteenth century, but this changed drastically in the sixteenth century, when visual documentation of fireworks displays rose sharply.

It is thought that the increase in visual records of fireworks during this parallels a rise in increasingly spectacular court life and royal celebrations. Several examples of fireworks from this period appear in the holdings of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University (as well as in the Paul R. Dupee Jr. '65 Collection on Fireworks). A brief discussion of some of the more dramatic versions of these displays will be discussed here. It should be noted, however, that the types of celebratory fireworks meant for entertainment discussed here are not to be confused with military fireworks, that is to say, those types of related, but less decorative gunpowder explosives used in warfare.

The illustration of fireworks necessarily entails use of a pictorial language that takes into account a representation of a quick, and fleeting burst of light. This momentary explosion is in contrast to the artistic rendering which is static, unmoving, and permanent. An early representation of fireworks held in this collection appears in The history of the coronation of the most high, most mighty, and most excellent monarch, James II, 1687, engraved by Francis Sandford, a festival book celebrating the coronation of James II of England. The image (Figure 1) is entitled, A Representation of the fire-works upon the river of Thames, over against Whitehall, at their majesties coronation (1685). This temporally impossible view displays exploding pyrotechnics which serve to “decorate” the centrally located sun, crown, and the King’s initials—all emblems standing in for the newly-crowned king. To either side are allegorical figures including “Pater Patria,” bearing two laurel crowns, and “Monarchia” riding a swan-like animal. The foreground is populated with swans and sea creatures that seem to be delighting in the spectacle. The subtly modulated all-over dark and light tones make it a particularly fine example of late seventeenth century firework representation.

A second, no less dramatic example of pyrotechnic display is included in a book of etchings and engravings by Jean Le Pautre, a noted artist who helped to popularize the Baroque ornamental style. Fifth Day of “Les divertissements de Versailles” (1676, Figure 2) depicts dramatic, corkscrew-patterned fireworks at a court festivity at Versailles to celebrate a recent military victory by Louis XIV (figure 2). This highly-complex theatrical event features the King’s sun-emblem in the center atop an obelisk. Two trumpeting angels on either side of the obelisk stand-in as representations of the booming acoustic element of any fireworks display. Reflected in the large pool in the middle ground are the what appear to be reflections of the exploding display above, but on closer inspection it becomes clear that the sky and pool are apparently depicting differing temporal moments. Regularly spaced figures of spectators sit and stand in the foreground—some in casual poses that further suggest an attempt on the artists’ behalf to overcome the difficulty of representing the fleeting moment in a static medium. André Félibien, author of this fête book, wrote the following about this dramatic fireworks display: “the entire decoration had a symbolic and mysterious meaning. In the obelisk and sun it was claimed that the king’s glory was etched in the striking light, and solidly affirmed above that of his enemies” (Salatino, 12). The unselfconscious poses of the spectators coupled with the differing temporal moments of the fireworks display represented here suggest a more complex attempt to represent time, space, and duration than is visible in the later example of James’ II coronation.

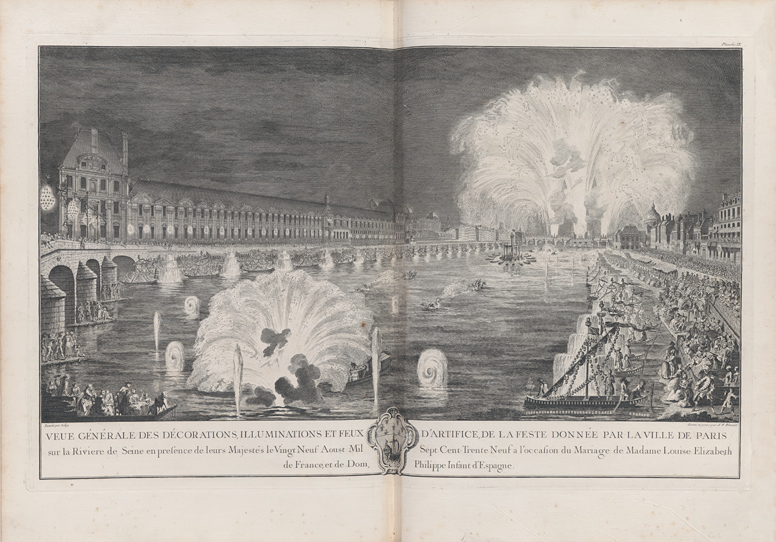

A final major example of courtly pyrotechny is from a lavishly illustrated festival book celebrating a royal wedding uniting French and Spanish lineages. Fireworks on the River Seine, Paris, 29 August 1739, for the marriage of Madame Louise Elizabeth and Don Felipe of Spain (1740, Figure 3) is from the book Description of the festival given by the City of Paris on the occasion of the marriage of Madame Louise-Elizabeth of France, and Lord Philip, prince and grand admiral of Spain, on the 29th and 30th of August, 1739 (1740). Jacques François Blondel is the engraver of this massive double plate whose splendor is second only to the depicted celebrations themselves. This scene, in marked contrast to those above, presents the viewer with a recessionary, more three-dimensional view rather than a flattened, more two-dimensional one. The river is littered with small boats bearing decorative candle lanterns, eager and energetic spectators, and exploding fountains. A battle of marine monsters is visible in the middle ground as is a specially-erected musicians’ pavilion that lasted only for the space of this festival. Again, we see here another attempt to render a specific temporal moment through formal devices and composition. The book describes the sequence of the fireworks explosions in careful detail, and the length of the duration of each. The depiction of two explosions, each in different stages of completion, suggests a deliberate attempt by the artist to conflate a temporal narrative into one unified space.

The differing examples of sequential representations of events as described in these three examples is just a brief overview of a complex system of representation at work in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to represent the spectacle and glory of fireworks displays. The experience of viewing fireworks may be elusive and short-lived, but their representation in static form, as seen here, has been permanently recorded for viewers then, now, and in the future.

Bibliography

Isherwood, Robert M. Farce and fantasy: popular entertainment in eighteenth-century Paris (New York :

Oxford University Press, 1986).

Salatino, Kevin. Incendiary Art: the representation of fireworks in early modern (Santa Monica, California,

The Getty Research Institute for theHistory of Art and the Humanities, 1997).