Artifice of Illusion: Architecture and the Manipulation of Landscape

Chelsea Tarvin

Description des festes données par la ville de Paris : à l'occasion du mariage de madame Louise-Elisabeth de France, et de dom Philippe, infant & grand amiral d'Espagne, les vingt-neuviéme & trentiéme août mil sept cent trente-neuf. Paris : De l'imprimerie de P.G. Le Mercier, imprimeur-libraire ordinaire de la ville, 1740

Description of the festival given by the City of Paris on the occasion of the marriage of Madame Louise-Elizabeth of France, and Lord Philip, prince and grand admiral of Spain, on the 29th and 30th of August 1739.

Turning the pages of this massive volume transports the reader into the world of 18th century France during which a remarkable event took place that changed, if only for a few days, the face of the city of Paris. On the 29th and 30th of August, 1739, the city witnessed two days of spectacles that transformed the familiar cityscape into a fantasy realm that challenged spectators’ perception of fiction and reality. The events, sponsored by the city of Paris, celebrated the wedding of Princess Louise-Elisabeth of France to Prince Philip, Infante of Spain. The festivities consisted of a lavish firework display over the Seine River and a masque, held the following day, in Paris’ City Hall. Both events relied heavily on transformative materials: the use of faux painting, fabric, ephemeral architectural elements, water displays and illuminations, to recreate familiar spaces and manipulate the natural environment in which the fête took place. As these changes were designed to dazzle, but only existed a few days at most, the festival book that describes them both explains the nature and creation of the ephemeral illusions as well as preserving a record of them for posterity.

The royal marriage that the fête celebrated was conducted by proxy on August 26th, 1739. Princess Louise-Elisabeth, the oldest of King Louis XV’s daughters, was a mere twelve years old at the time of the ceremony. She did not meet her nineteen year old husband until they were formally wed in Madrid during October of the same year. The Spanish royal family was not present at the fête although allusions to their house were a persistent theme in the festival decoration. The Spanish prince, Philip Infante, was the third son of Philip V. It is rumored that news of the marriage was not well received at court as Philip was the youngest son of king and not likely to succeed his father. If this was the case, the fête may well have been designed to hide the court’s displeasure with the match. However, the festival book gives no indication that the marriage was anything but a joyous occasion.

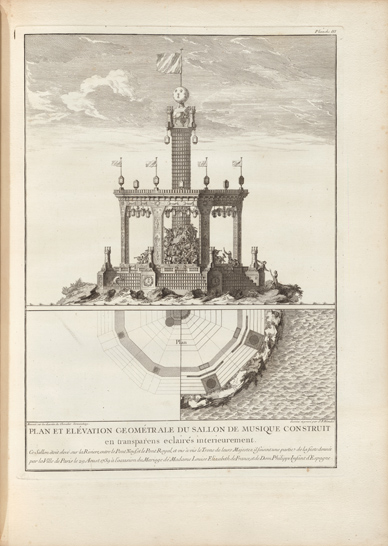

The first image depicts an artificial island constructed upon the Seine River. The text of the fête book relates that the structure was suspended on two large boats which were concealed beneath the artificial rock outcroppings along the island’s perimeter. A detailed diagram of the building’s plan can be seen in conjunction with a rendering of its appearance during the fête. The island contains a grand octagonal salon where eighty musicians play to the delight of the crowd seated along the river’s banks. The reader is told that the façade is painted to resemble white marble and was further embellished with figures of the muses. Lanterns and flowered garlands hang amidst the jovial musicians, contributing to the festive atmosphere. A singular column, said to stand forty-four feet high, dominates the upper section of the structure. It is adorned with vari-colored transparent fabric that is illuminated from within. Atop the column sits a massive globe, painted blue, which conspicuously displays the symbols of both royal houses: the towers of Castille and the French fleur-de-lis.

The illustration of the island’s structural diagram (Figure 1), and the extensive description of its adornment in the book’s text, attest that the island’s ingenious construction and nuanced decoration made it a significant component of the spectacle. However, the island could never fully deceive the crowd as it drastically altered a well known public landmark. The appearance of the city was purposefully manipulated on a grandiose scale in a way that was never meant to be imperceptible. The citizens of Paris would instantly recognize that the island was not part of the natural landscape, but an illusionary construct on the river’s surface. However, rather than detracting from its ability to awe, in fact it added to the island’s captivating quality. The entirety of the structure was created for the conspicuous consumption of the spectators. They were meant to be astounded by the city’s ability to build an ephemeral structure of such luxury that would only survive for the duration of the fête. However, the island in the middle of the Seine was just one element of the splendid display provided for the enjoyment of the city.

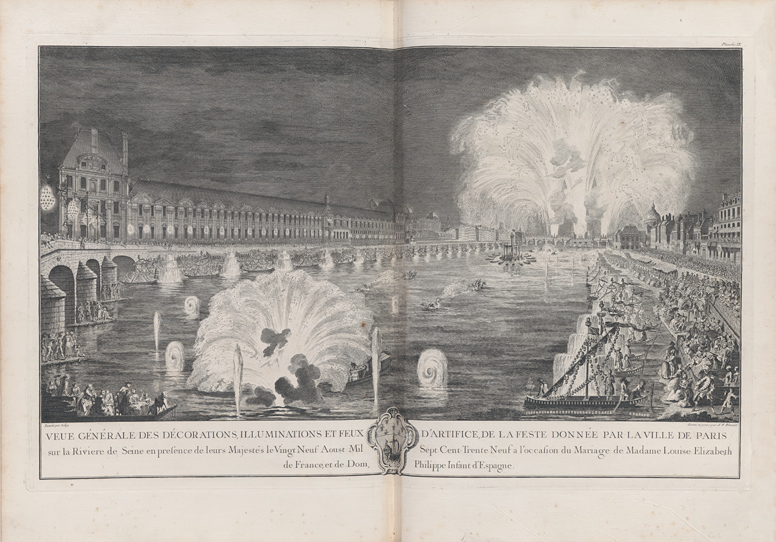

Figure 2 depicts a panoramic view of the entire spectacle that took place between the Pont Neuf and the Pont Royal. In this view, the size of the artificial island is trumped in comparison to the water and firework displays. The reader’s eye is immediately drawn to the distant bursts of fireworks that transform the dark night into brilliant light. Three hundred ground displays and two hundred boxes of flying fireworks were set off along the Pont Neuf. Other notable pyrotechnic displays also occurred in and around the façade of a Greek temple constructed on the Pont Neuf for the occasion. One such display was created in the semblance of a sun, sixty-four feet in diameter, which can be in this image above the temple façade.

While this fête is often described as a firework show, the ingenious water displays were equally impressive and closely tied to the spectacle’s illuminations. Amongst the many fountains on the Seine we see a magnificent fan of water issuing from a boat in the image’s foreground, which mimics and exaggerates the shape of the fireworks beyond and links the two primary themes of the spectacle, fire and water. The water features take a variety of forms, from sea creatures that breathe “firewater” arranged in mock battle, to elaborate fountain displays of jets and pinwheels. A description of each, including an explanation of the feature’s mechanics, can be found in the book’s text. Reflected in the eddying water was the brilliance of the light emanating from the spectacle’s illuminations.

Illuminations were a central decorative feature of the fête and were closely tied to their watery surroundings. Chandeliers of lights were strung along the river’s edge and on the bridge’s which enabled the crowd to more clearly see the extravagant decorations and gave the city a luminous quality. A fleet of illuminated boats is said to have issued from the Pont Neuf before docking along the river’s edge. The boats, totaling sixty in number, were brightly painted and each contained a different arrangement of lights, held in glass cases and strung along a thirteen foot mast. The radiance of the numerous illuminations was amplified by their reflective glass casing and mirrored in the waters of the Seine which “doubled the quantity of lights” to the delight of the many onlookers.

The expanse of the river, from the Pont Neuf to the Pont Royal, is crowded with animated spectators who watch in awe at the spectacle before them. Strategically positioned at the center of the extravagant scene is the royal family. While their central placement gave them an optimal position from which to view the fête, it also enabled the crowd to have a clear view of the persons for which it was held. The ability to see the royal family was undoubtedly considered a highlight of the event. Their viewing box, created specifically for the fête, was attached to the Louvre, then the palace of the king, and painted to give it the appearance of a permanent marble structure with gilded accents. This elaborate ephemeral façade both framed the royal family and embellished the royal residence.

During the spectacle, the crowd witnessed a monumental transformation of the cityscape where opposing elements seemed to coexist: fire and water, light and darkness, the novel and familiar. The book’s text relates that all the elements of the fête were carefully planned and timed with great accuracy so that each feature worked in concert with the others. The sight of the king, the brilliance of the fireworks overhead, the parade of illuminated boats sailing amidst gushing fountains, all moved to the score of the music that emanated from the artificial island and created a fantasy realm within the heart of the city.

The following night, a ball was held in Paris’ City Hall that was said to be a spectacle “even though of another sort, [. . .] equal to that of the fireworks and illuminations of the night before.” The well known civic building was altered through the use of ephemeral architecture and adornment (Figure 3) to the extent that it “no longer had the layout that one knew.” In fact, the transformation was so complete that it formed a spectacle in itself and the building’s unique decoration could be viewed several days in advance of the event. A temporary columnar façade was erected to cover the walls that were painted to resemble white-veined marble. Festoons and garlands were draped over faux gilded urns, and crystal chandeliers were hung along the architrave. A total of 1,700 lights lit the room and made it “like daylight.” However, the most remarkable feature and that which is featured most prominently in the fête book, was the vast suspended ceiling.

Painted to resemble a serene sky, the enormous piece of waxed canvas was pulled taut by ropes, prominent in the illustration, over the entire span of the roof to protect the revelers from adverse weather. The bottom of the canvas was illusionistically painted to seamlessly continue the roofline of the hall’s ephemeral façade. Painted trees and festoons even seem to hang from the upper balustrade. Even though the ball took place at night within the courtyard of the city hall, the painted ceiling and other decoration combine to create the semblance of a sunny outdoor salon. The mechanics of the ceiling’s suspension and the architecture of building are clearly illustrated in the fête book. The degree of interest in the structure’s design reflects the pride that the artificers took in the execution of their craft. It is not just the atmosphere that is conveyed through the image, but a detailed account of the ephemeral elements that so completely transformed the building for a short time. The images and descriptive text reveal the nuance of the decorative scheme and in so doing, indicate that the illusion created during such spectacles was an event in its own right.

The two storey hall was divided to create spaces for dining, dancing and watching fellow guests. Four thousand tickets were distributed in advance of the ball. The attendees, the book relates, consisted of the royal family, the entire court and “all the people of Paris of consideration.” The eager guests entered through a narrow passage which opened onto a grand, open courtyard filled with music and conviviality. An orchestra of eighty musicians played from a set of bleachers constructed for the event. After dancing, guests could enjoy a delicacy from one of the six rooms set aside for buffets that were filled with pastries, liquors, wine, iced cream and fruits, including a purported fifteen thousand peaches. However, the true spectacle of the event seems to have been the guests themselves, who are seen in the book talking animatedly and enjoying the jovial atmosphere of the fête.

The illusionary imagery of the fête was specifically designed to challenge the spectators’ traditional perception of Paris. Fabric, illuminations, water and firework displays, and faux painting all worked in concert with music and other elements of the spectacle to transform the well known monuments of the city. During both the firework display and the masque held on the following night, both the city and its landscape were manipulated. Islands were made to appear on the Seine, water could be confused with fire, entire buildings were refaced, and night became day. These spectacles challenged the guests’ perception of reality. However, in the fête book, the nature of these artifices of illusion is revealed in detail. Written descriptions, renderings from multiple view points, and architectural plans proudly expose these artificial constructions for what they are, ephemeral elements that were conspicuously consumed for the amusement of the public and the glory of the royal house. It was a source of pride that such extravagant ornamentation could be conceptualized and produced for so short an affair. And it was certainly a spectacle of equal impressiveness, when the realistic facades were disassembled and the face of the city of Paris reemerged, just as she was before the fête.