Funeral as Festival: "It is Fitting Even for a Prince to Die."

Nathaniel Walker

Giulio Vasco (1640-1700). Del funerale celebrato nel duomo di Torino all’Altezza Reale de Carlot Emanuele II, duca di Savoia… [The Funeral Celebrated in the Cathedral of Turin for His Royal Highness Carlo Emanuele II, Duke of Savoy…]. Turin, Italy: ca. 1676.

When Carlo Emanuele II, Duke of Savoy, inherited his title in 1638, he also inherited a grand but unfinished legacy of monumental construction in his capital city of Turin. His father, the Duke Vittorio Amedeo, had been passionate about the importance of architecture since he was a youth, both for the sake of aesthetic beauty and as a venue for the expression of political power (Pollack, 83). To these ends he had worked to enlarge the city’s fortifications and improve its principal streets and civic plazas. But the untimely death of Amedeo in 1637 plunged the duchy deep into an international conflict that had been threatening it for decades–and while the city lay half-finished, the house of Turin fought for its survival.

In 1663, after the long and ultimately successful regency of his mother, the young Carlo Emanuele II came to power and immediately began taking advantage of the relative peace in order to begin consolidating his realm. For the young Duke, this meant more than military fortification or the completion of his city–he also set about attempting to purge his lands of Protestants, and became so notorious for his cruelty against the Vaudois (the Waldensian sect of Reformed Protestants) that in 1655, after the duchy was wracked by sectarian violence at least partly ordered by the Duke, Oliver Cromwell published an account of the violence entitled The Barbarous and Inhumane Proceedings Against the Professors of the Reformed Religion within the Dominion of the Duke of Savoy, graphically illustrated “that the eye may affect the heart” (London, frontispiece). But the Duke, who aspired not only to a unified duchy but also to the royal title of kingship, worked hard to maintain strong ties with the powerful papal authority of the Roman Catholic Church, and did not waver in his religious and political convictions.

He did, in the end, also set about the task of completing his capital city, which was rapidly expanding and required both new fortifications and careful guidance if it was to grow along the Baroque lines drawn by both Carlo Emanuele and his long-deceased father. The duke ensured the development of magnificent and stately boulevards, enormous buildings fronted by elegant squares (including the Palazzo Reale), and a number of important religious structures. But, while out one morning on horseback, surveying the work underway, he fell ill and developed a fever. In time, the illness grew worse, and the Duke realized that he would die. After years of working to protect and extend his power, and after exhausting so much time and wealth in the construction of a capital city that would adorn his realm and resonate with his greatness, Carlo Emaneule II was confronted with his own mortality–indeed, his entire domain was confronted with it. In a period of European history in which rulers were often understood as living microcosms of the peoples and places they ruled, “not an individual human being but a representative figure” (Watanbe-O’Kelly, 10), this presented no small problem. When “the health of the king’s body” was directly related to “the health of the state” (Zanger, 67), how could the death of the ruler not spell disaster for both royal house and royal domain?

Death may spell the end for a particular monarch’s earthly tenancy, but it also makes way, ideally, for a new ruler: “The King is Dead! Long Live the King.” By staging an elaborate public funeral that reinforced the greatness of the fallen Duke while also celebrating the enduring power of his legacy and family, the duchy could ensure the semblance, at least, of continuity, and prevent the demise of the ruler from becoming, symbolically or otherwise, the demise of the domain. With this in mind, Carlo Emanuele II asked that his bedroom doors be opened, so that his court could witness his final breath. To this request he added the words: “It is Fitting Even for a Prince to Die,” a courageous statement which claimed his own demise as a victory of civic decorum. Meanwhile, a local Jesuit father, Giulio Vasco, was asked to prepare a monumental civic funeral, on a scale and of such quality that it would pay due homage to the deceased Duke while signaling the victorious and powerful rise of his widow, the duchess Giovanna Battista, who was to act as Regent until her son came of age. So that the event would never be forgotten, the Jesuits were also asked to prepare an illustrated book recording the event and its key moments–this is the book from which the accompanying illustrations are taken.

Figure 1: The temporary façade of the Cathedral of Turin, erected for the funeral of the Duke of Savoy, from Del funerale celebrato nel duomo di Torino all’Altezza Reale de Carlot Emanuele II, duca di Savoia…, ca. 1676.

The state funeral that followed the death of Carlo Emanuele II transformed his blossoming capital into a stage for mourning on a royal scale. An enormous procession saw the royal corpse taken from the Palazzo Reale to the cathedral. The cathedral itself, home to the Catholic Church so beloved by and important to the Duke, was draped in black canvas and given a new façade that would speak to the solemn occasion, using temporary materials such as wood, plaster, and canvas (Figure 1). It was a classical Baroque composition, but used, rather than Doric or Ionic columns, a “funereal order” (Pollack, 242) in which pilasters adorned with mourning figures supported an entablature filled with skulls and crossbones. Resting on the pediments were allegorical figures, “Time and Death dominated by Valor,” as well as “Vice and Envy vanquished by Virtue” (Pollack, 243). Above the door was a winged Death’s Head, and above this a large painting framed by the lions of Savoy, which featured the Duke on horseback surveying his grand construction projects and accompanied by architects and engineers, at the moment they are stopped in their tracks by a winged figure of Death brandishing an hour glass and pointing heavenwards. This was, of course, a representation of the morning on which the Duke fell ill, and using the iconographic traditions of martial royalty, the image presented the tragic conclusion to his building campaign as civic heroism. An inscription informed mourners how to interpret the grand ceremony: as a victory of the surviving duchess over the tragic death of her husband.

Figure 2: The magnificently gloomy transformation of the nave of the Cathedral of Turin, designed for the funeral of the Duke of Savoy, from Del funerale celebrato nel duomo di Torino all’Altezza Reale de Carlot Emanuele II, duca di Savoia…, ca. 1676.

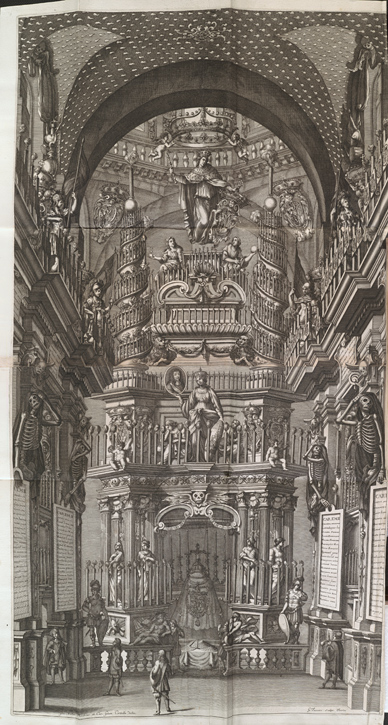

Figure 3: The baldachin constructed for the apse Cathedral of Turin, erected to hold and frame the royal corpse during the funeral of the Duke of Savoy, from Del funerale celebrato nel duomo di Torino all’Altezza Reale de Carlot Emanuele II, duca di Savoia…, ca. 1676.

The interior of the cathedral was also completely transformed (Figure 2). The ceiling was draped in black cloth and covered with thousands of silver tears, candles flickered everywhere, and enormous skeletal figures filled the nave. These figures acted as gloomy Caryatids, supporting a deathly, skull-emblazoned column capital on their heads with one bony hand, and bearing enormous placards testifying to the noble deeds and virtuous qualities of the fallen Duke with the other. Between them were paintings depicting key moments in the life of Carlo Emanuele II. Terminating the nave, at the altar, an enormous baldachin, ablaze with candles and swarming with allegorical figures, seems to have suggested the glorious ascendance of the Duke’s soul (Figure 3). His body lay beneath it, and his portrait was held aloft at its center.

Casting a cold but nonetheless brilliant light over the fallen glory of the Duke, this elaborate funeral was a public festival of mourning, a celebration of sorrow. And the events, combined with the magnificent stages which framed and supported them, not only provided a venue for a bereaved kingdom to publicly grieve, they also simultaneously reinforced the suitability of the dead king’s heir, whose presence and legitimacy were demonstrated in part by the spectacle of civic lamentation conducted on a royal scale. The magnificent but nonetheless temporary architecture, adorning the city so beloved by its ruler, was also meant to be remembered forever: not in the streets and squares which were transformed for the occasion, perhaps, but certainly in the book that recorded this funeral-as-festival for posterity.

Bibliography

The Barbarous and Inhumane Proceedings Against the Professors of the Reformed Religion within the Dominion of the Duke of Savoy. London: Printed by M. S. for Tho: Jenner at the South-Entrance of the Royall Exchange, 1655.

Pollack, Martha D. Turin 1564-1680: Urban Design, Military Culture, and the Creation of the Absolutist Capital. University of Chicago Press: 1991.

Watanabe-O’Kelly, Helen. “The Early Modern Festival Book: Function and Form.” In Mulryne, J. R., Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly, and Margaret Shewring, editors. Europa Triumphans: Court and Civic Festivals in Early Modern Europe. Aldershot, Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2004.

Zanger, Abby. “Lim(b)inal Images: ‘Betwixt and Between’ Louis XIV’s Martial and Marital Bodies.” In Melzer, Sara E. and Kathryn Norberg, editors. From the Royal to the Republican Body: Incorporating the Political in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century France. Berkeley: University of California Press: 1998.