British Portrait Vignettes

Samuel Williams Reynolds

Jeffrey, Lord Amherst, 1766

Samuel Reynolds's print of Jeffrey, Lord Amherst was made after a sketch by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Here, mounted on a charging horse, Amherst is shown in action, although the battle in the background, where men carrying flags fight on horseback, does not seem to involve him directly. The engraver employed the common practice of adding etching passages to strengthen the mezzotint, and many individual lines have been introduced in the engraving process as modeling or detailing.

Sir Jeffrey was a popular subject in mezzotints because of his considerable status as a military figure. Of this print, there are two engraver's proofs and four impressions. Four more prints of Amherst were made after paintings by Reynolds, including a portrait in an oval frame that illustrated Smollet's History of England of 1757. A print of Sir Jeffrey after a portrait by Gainsborough also exists. James Watson was Reynolds's preferred engraver in the decade 1765-1776, after the engraver McArdell's death.

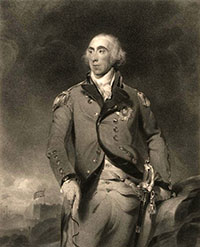

Joseph Collyer after Sir Thomas Lawrence

Sir Charles Grey, 1797

Sir Charles Grey, the first Earl (1729-1807), is silhouetted against a stormy sky in this stipple engraving by Joseph Collyer after a painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence. The painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1795 1 following the General's return the previous year from the Caribbean, where he had aided in the British capture of the French West Indies. This portrait commemorating that victory depicts Sir Charles standing supported by a cane, on the rocky hills overlooking a crenulated harbor fort that flies the British flag.

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) here employs conventions common in formal military portraiture. The lack of a middle ground between the subject in the foreground and the distant scene in the background distorts the sense of scale and makes General Grey appear gigantic. The very low horizon line places the viewer well below the subject, who appears to 100m large and heroic against the stormy sky.

Painting in the grand manner advocated by Sir Joshua Reynolds, Lawrence secured his reputation with images of elegant, dramatic heroes. In 1815 he was commissioned by George IV to paint the portraits of the allied military leaders and statesmen in celebration of their victory in the Napoleonic Wars Upon the death of Benjamin West in 1820, Lawrence became President of the Royal Academy, serving until his own death in 1830.

The engraver Joseph Collyer translated Lawrence's portrait into a stipple engraving in 1797. This medium had become increasingly popular for reproducing portrait paintings in the late eighteenth century. Like mezzotint, stipple engraving produces a tonal rather than a linear effect, and while both techniques are well suited to rendering the chiaroscuro effects in oil painting, stipple engraving is easier to produce than mezzotint engraving. Neither technique is well suited for handling large-scale paintings; broad expanses of stipple work quickly become monotonous. By emphasizing the contrasts between the light and dark areas and between the refined detail of the face and simply treated expanses of sky and fabric, as well as by highlighting the gleam of the General's buttons and trim, Collyer avoided monotony and skillfully enlivened the stippled surface.

James McArdell and Robert Houston After Sir Joshua Reynolds

Charles Lord Cathcart

This mezzotint of Charles Cathcart by James McArdell and Robert Houston, two of the most gifted of the "Dublin Group" of Irish engravers, is done after a painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Reynolds exploited classical and Renaissance styles in the 1760s and 1770s, and the pose and atmosphere of this portrait reflect these concerns; Cathcart's pose, for instance, is reminiscent of Titian's Man with a Glove (The Louvre, Paris) from about I523. The formal military portrait derived from the conventions of court portraiture, and the choice of a courtly model for this portrait was well suited to its subject. Charles Cathcart, the ninth Baron Cathcart (1721-1776), participated in the aristocratic as well as the military worlds, and at the time this print appeared, was British Ambassador to the Russian court of Catherine the Great.

In the portrait, Lord Cathcart stands before a balustrade, framed by heavy plush curtains and wearing an elegant uniform with a cuirass. He engages the viewer with his direct gaze, slight smile, and a gesture of greeting made with slender, tapering fingers. His hair is powdered and a black crescent patch graces his cheek. Light raking across the scene from a window behind the drapery creates the opportunity for the chiaroscuro effects for which mezzotint is so well suited.

This print is in the second state the first state was left with its edges uncleaned at the time of McArdell's death at 36 in 1765. Houston may then have completed the print, as the inscription notes: Jas. McArdell delineavit (a word which, like pinx, usually refers to the painter or draughtsman), R. Houston perfect (finished). The Irish engravers usually published their work themselves, but upon McArdell's death, the print seller Robert Sayers came into possession of his plates. This print, published by Sayers in 1770, was probably among the more than one hundred McArdell prints listed in Sayer and Bennett's 1775 catalogue.

H.S. Minasi After Agostino Aglio

The Marquis of Wellington, K.B. &c. &c. &c. at the Battle of Salamanca, 1812.

This is an engraving after a painting or drawing by Agostino Aglio, now lost. Aglio came to England from Italy in l803 with William Wilkins, R. A. Known mainly as a landscapist; he also painted subject paintings, portraits, and theatrical scenes, was involved in engraving and lithography, and was a successful decorator. Nothing more is known about his composition of Wellington at the Battle of Salamanca than what can be seen in the engravings by J. Quilley and this version by H. S. Minasi.

Little is known about the engraver H. S. Minasi. Two other artists of the same last name also were active in the same period: James Anthony Minasi, a student of Fr. Bartolozzi, who was a stipple engraver and lithographer, and Giacomo Minasi, who worked as a stipple and crayon manner engraver of portraits and decorative subjects. Although this particular portrait of Wellington is sometimes attributed to Giacomo, it was done by H. S., who was probably part of the same artistic family.

This engraving is typical of the vast number of inexpensive Wellington portraits done in response to his overwhelming popularity as a hero, even before Waterloo and his elevation to a dukedom. Here he leads the charge in the decisive Battle of Salamanca on July, 1812; in this battle the French general Marmont was defeated, leading to the eventual British victory over the French in the allied campaign of 1813. The mediocre quality of this representation is evident in the arbitrary hand coloring, which serves to flatten the portrait. The ease with which crayon manner engravings like this were created and reproduced demonstrates how the high demand for images not only of Wellington, but also of heroes in general, was filled at all economic levels in British society.

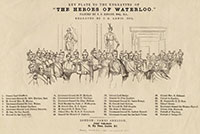

Charles G. Lewis after John Prescott Knight

Key Plate to the Engraving of "The Heroes of Waterloo", 1841

In 1842, the Royal Academy exhibited John Prescott Knight's painting The Heroes of Waterloo (Collection of the Marquess of Londonderry, Wynard Park). Completed in 1840 this work depicts the Duke of Wellington and his guests al his annual banquet for the heroes of the Battle of Waterloo on June 18, the anniversary of the 18/5 victory over Napoleon. The Duke began this tradition in 1817 or 1818, and held these banquets Apsley House, his London homc, until his death in 1852.

Knight, a member of the Royal Academy, was a prolific artist who painted many aristocratic Victorians and often engraved many of his own portraits. However, Knight's The Heroes of Waterloo was engraved by Charles G. Lewis in 1841 as Waterloo Heroes Assembled at Apsley House on 18th June 1842. Lewis, a younger member of a prominent family of artists and engravers, produced a color engraving accompanied by a key plate. Knight's painting was reproduced again in 1848, this time in a lithograph by S. Lipschitz published in both London and Hamburg and re-titled The Waterloo Heroes Assembled at Apsley House. The print shown here is that by Lipschitz, with the key plate from Lewis's earlier version.

In Lipschitz's print, the figures group around Wellington, who is additionally framed by paintings of Napoleon and George IV on the back wall of the room, as noted on the key. Each officer is identifiable by his medals, ribbons, and regimental uniform, as well as by his actual portrai1. This annual celebration and reunion of the heroes of Waterloo was portrayed by other painters and printmakers of the time, notably in William Salter's The Waterloo Banquet of 1836, which was engraved and published in London in 1846 by William Greatbach. In this same year, Knight painted what seems to be a companion piece to the Heroes of Waterloo, Heroes of the Peninsula (now also at Wyndam Park), which was engraved by Frederick Bromley in 1847 and displayed at the Royal Academy in 1848

Attributed to Matthew Darly

A Smart Macaroni, c. 1776

Matthew Darly was both a printer and a publisher: he owned a print shop with his wife, Mary, at No. 39 The Strand in London. In addition to printing other artists' "sketches or Hints sent post paid" as well as engraving Chippendale's furniture designs, Matthew Darly made his fame as a caricaturist with his series of satires on macaronis. Many of these caricatures, designed by him and other contributors, were published in a bound series entitled Comic Humour. Caricatures &C. in a Series of Droll Prints. Consisting of Heads, Figures, Conversations, and Satires upon the Follies of the Age Design'd by Several Ladies, Gentlemen and the Most Humourous Artists. &c.

The term macaroni, first used to describe a type of late fifteenth-century verse, was applied in late eighteenth-century England to dilettantes who had just returned from the Grand Tour. The figure in this caricature wears the macaroni's typical long braid and stands in a landscape next to a large tree, blowing a horn. He is called a "SMART" macaroni in the title. The only Smart recorded in the army lists of 1759-1781 is one Lieutenant Robert Smart, a member of the 10th (North Lincolnshire) Regiment of Foot in 1781. His pig-like features maybe the reason he is called a "Hog in Armour." The macaroni fad went out of fashion in 1776, and therefore this print was probably executed towards the end of Darly's career.

James Gillray

The Death of the Great Wolf, 1795

Gillray parodies Benjamin West's painting The Death of General Wolfe in this satire of the passing of the Treason and Sedition Bills December 18th, 1795 by the Pitt ministry. These bills prohibited gatherings of more than fifty people without advance notification to a magistrate, and penalized anyone who wrote or spoke against the Constitution. Gillray replaces Wolfe with Pitt, the "Great WOLF," who is dying, ironically, at the moment of his political victory. He has formed a coalition government, and with these bills has succeeded in quelling any opposition to the war with France. Gillray may have depicted Pitt as dying to imply that the passing of these bills, which severely restricted freedom of speech, might cause Pitt's political ruin.

Pitt is attended by members of his coalition ministry and politiCal supporters. He was known as a heavy drinker, and here his drinking companion and Secretary of War, Henry Dundas, offers him a last glass of wine. Richard Pepper Arden, Master of the Rolls, wears an anguished expression as he supports Pill's sagging body, and Edmund Burke, a strong supporter of Pitt and the Tories, kneels next to Arden Burke retired from Parliament in 1794 and year later received a pension from the ministry: Gillray emphasizes Burke's attachment to Pill by placing a piece of paper (possibly the beginning of a new book) in his pocket inscribed "Reflections upon £ 3700 Pr Ann." Lord Chatham (Sir John, Pin's brother), Lord of the Privy Seal, stands behind this group holding a flag, the symbolic representation of the king. The flag is decorated with the white horse of Hanover galloping over the Magna Carta, signifying the suppression of constitutional rights by the king and his ministry. Beside Chatham stands Thomas Powys, an independent country gentleman who was active in politics and supported these bills. In front of this central group Gillray repeats the tricornered hat in West's painting but replaces the musket with an unsheathed sword; a civilian's top hat rolls away to the right.

To the left of the central group are six men. The kneeling figure who replaces the Mohawk Indian in West's painting is Loughborough, the Lord Chancellor, a Whig who supported the forming of a coalition government. He is decorated with the attributes of his office, the Great Seal of Britain, a scepter and a judge's robe and wig. However, he also has a bloody axe near him, indicating his guilt in the slaying of personal freedom. Above him are the two Secretaries of the Treasury, George Rose and Charles Long, who encourage Pitt to hold on (despite Pitt's terrible management of national finances). Lord Mansfield, Chief Justice of Common-Pleas, and William Windham, Secretary at War, hold back the grieving William Grenville, Pin's Foreign Secretary and the main supporter of the Treasonable Practices Bill in the House of Lords. Two more of Pitt's supporters are placed at the far right of the composition. The crying figure with a wooden leg is William Wilberforce, who also endorsed the Treasonable Practices Bill in the House of Lords. The grieving figure next to him has been identified as the Duke of Richmond, Master of the Ordinance, although he resigned from this position in 1794.

The messenger at the left in West's composition has acquired a demon's face in Gillray's print. Carrying the tattered Libertas banner of the defeated Opposition, he shouts the message of victory. In the smoky background, the battle is played out by an overwhelming ministerial force, carrying the banner of the crown, which easily destroys the Opposition forces represented by the sans-culottes Jacobin sympathizer.

Although Gillray may not have approved of the restriction of constitutional rights inherent in these bills. He portrays Pitt in a composition traditionally reserved for the dying hero. The purpose of these Seditious and Treasonable Practices Bills were to prevent the expression of anti-war feelings, and Gillray was a great supporter of the war with France. Thus, while satirizing the restrictions placed on the freedom of speech and their potentially disastrous political implications for Pitt and his ministry, Gillray is also acknowledging the need to contain opposition to the war and to sustain the British form of government, a constitutional monarchy, which was thought to be severely threatened by the French Revolution.

Anonymous

Winging a Shy Cock, 1808

Eleven days before the publication dale of this print, March 29, 1808, Lieutenant-General John Whitelock (1757-1833) was court-martialed and cashiered. Shown here standing dejectedly with knees bent and facing left,Whitelocke is further humiliated by IWO small drummer boys: one, seen from behind, cuts off his epaulets while another, standing on a drum and grimacing with delight, breaks a sword over his head. On the ground lie Whitelocke's dismantled regimental trappings including buttons, scabbard, and sash. Behind him the musical score entitled "The Rogue March" alludes to his disgraceful behavior in the army.

In 1807 Whitelocke was appointed to command over 8.000 troops and regain possession of Buenos Aires. He bungled the attempt. On July 5, believing the citizens friendly, he sent troops into the town with unloaded guns. They met with stern resistance. Enemy troops encountered them in the streets and the townspeople bombarded them from their rooftops.

Thousands of British soldiers were killed and Whitelocke was forced to surrender and return to England in shame. Not only was his direction inept, but during the massacre he was nowhere to be found, an absence construed as cowardly, as was his eventual surrender. This cowardice is satirized here by the devil who proffers him a cocked gun and says "Now Fellow if thou hast a spark of courage left take this," while Whitelocke hesitantly responds "Have you taken the flint out[?]" The devil suggests suicide but Whitelocke does not have the courage to act on his advice.

Whitelocke must have been well known in 1808, as Fores published several caricatures of his military blunders and subsequent degradation. In fact, his name became a by word: it was fashionable to say a person was "Whilelocked" if they had been disgraced.

The meaning of the title "Winging a Shy Cock" is somewhat problematic. The word "cock" can signify a leader or master. Thus, the winging of a shy cock could be the removal of the cowardly leader's epaulets, as depicted here. This image of the pitiable Whitelocke, robbed of all his military finery and encouraged to commit suicide, shows him as a figure to be ridiculed.

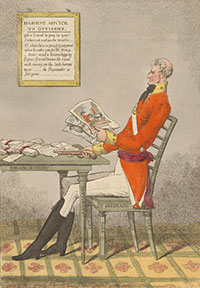

Veritas (Pseud.), Attributed to Charles Williams

My Bane and Antidote now lye before m, / This in a moment

brings me to an end / But these inform me I shall never die!!-Cato,

1811

The engraver with the ironic pseudonym "Veritas" portrays the disgraced Lieutenant Godfrey Green. The tall, slender, rather dandified Green sits facing left at a table littered with documents marked "Letters from Lawyers," "Court of Inquiry," "Reasons for quilling my last regiment," and a large stack labeled "Bills." On the table are inscribed the words "Breach of Trust" and "Obstinacy," while an even c1earersense of Green's character is given by the inscriptions his chair: "Disgrace," "Incorrigibleness," and "Lies."

Green was accused in 1811 of misappropriating funds from the army paymaster in order to settle his own accounts. A framed motto on the wall behind him attests to his predilection for unilateral loans: "Dashing Advice to Officers.. .If your friend leaves the room with money on the table borrow some – the Paymaster is fair game. –" Green was never indicted for his actions, but in the same year he was transferred from the 87th Foot to the 34th, possibly in an attempt to quash suspicions of dishonorable behavior. On his buttons and sword belt is inscribed the number 34, indicating his recent transfer. His actions occasioned numerous prints satirizing his greed and corruption.

Green holds in his left hand three caricatures of himself, also published in 1811. Two of these, similar in format to this print, depict Green facing left, seated at a table, and either stealing money or ripping up caricatures of himse1f. The third, visible under Green's thumb, shows him serving sentence in the stocks. In his right hand he holds a gun marked "Courage" on the stock and the initials "G. G."on the butt. The title below the image describes his actions. The "bane" of his existence is both the debts that he stole to pay and the caricatures that continue to slander his name. The "antidote" to his situation is suicide, but even in death the caricatures will survive to continue his infamy. The quote from Cato, which serves as the title, may have been taken from a dramatization of Cato's last hours before his suicide at Utica. While Green never committed suicide, the demand for prints caricaturing his folly assured his public humiliation.

Anonymous

Military Prodigies - or the Fatest, the Tallest, & Smallest, 1822

This print is a good example of how portrait caricature employs distortion and exaggeration. Whatever these figures did to cause this satire, if anything, is not reproduced here. Instead, they seem to be satirized simply for their appearance. The figures caricatured here are officers from the First Regiment of Dragoon Guards. As indicated by the 18th army list, the "Smallest" is Lieutenant Colonel George Tisdall, the "Fatest" is probably Captain Richard Heaviside, who may be caricatured for his name as well as his actual appearance, and the "Tallest" may be Captain Richard Martin. It evident however, that these men are described as prodigies not because of any military talent but instead for their extraordinary physical features.

Anonymous

Captain the Honorable Edward Thomas Gage, 1854

By the 1880s, English watercolor painting was famed world-wide and had become associated with landscape painting through the popularity of landscape by Turner and Whistler. But landscapes were not the only watercolor images created in England in the nineteenth century. Many Victorian watercolor portraits were produced, primarily of soldiers and dandies.

Watercolor is a difficult medium for portraiture, since the precision required to capture details of a particular face is far more easily achieved in other media. To avoid a distracting mixing of colors on the paper surface, Victorian artists tended to lay the watercolor over a sketch in ink or pencil, thus giving the works a clarity of form similar to that found in oil paintings. Such a pencil sketch lies beneath this unattributed watercolor the artist probably sketched his sitter's likeness from life and added the watercolor later. He worked on light board, which gave him better control of form and color than paper.

The setting of the portrait lacks the clarity of form found in the likeness and is left somewhat ambivalent. From what we know about nineteenth-century English watercolors, it is possible to suggest a few reasons for this lack of specificity. While some watercolors were painted en plein air, most were repainted or "finished" in the artist's studio. The artist of this portrait probably painted only Gage's likeness from life. The remainder of the composition was a product of the artist's imagination, the landscape probably a composite of the artist's knowledge of English landscape painting and his knowledge of Crimean scenery, and the curious little cannon included for its martial connotations. Even the sword appears to have been a later, atmospheric addition.

The portrait depicts Edward Thomas Gage (d. 1889), a captain in the Royal Artillery, on the day of his departure from England for the Crimean War. As there are no known portraits of Gage in other media, we cannot assume that this watercolor is a study for an oil. It may well have been made as a personal document. Prior to the Crimean War, Gage led an unremarkable military career. His posting to the Crimea may have seemed to him a turning point, a chance to achieve distinction. A watercolor portrait would have been a reminder of Gage's fearless departure, and also a private family record, a memento of Gage, perhaps, should he not survive the war.

Joseph Cundall and Robert Howlett

Crimean Braves--Men of the Trenches and Battle field in the Crimea,

Coldsteam Guards--Privates, 1856

The photographers Joseph Cundall (1819-1895) and Robert Howlett (1831-1858) are best known for their images of Crimean veterans. Cundall, a writer of children's books and a publisher, was a founding member of three of Britain's early photographic associations, the Calotype Club (1847), the Photographic Club, and the Photographic Society (1853). Howlett contributed photographs to the Photographix Exchange Club and the Photographic Society. Before working with Cundall, he worked from 1854 to 1858 with Georges Downes on photographs for the illustrated London News

Cundall and Howlett's most important collaborations were two commissions, both for Queen Victoria, for which they photographed the veterans of the Crimean War. Originally intended for albums in the royal collection, the photographs were made in to a series of 25 images geared towards the commercial market and sold as albums entitled Crimean Heroes or Crimean Braves. The photographs also appeared in illustrated newspapers and in exhibitions.

The photogravure by Holdgate was executed from a photograph of the 42nd Highlanders and published in 1857 by the Photo-Galvanographic Company. This portrait of Privates Nunn, Potter and Deal appeared in the Photography Society's 1857 exhibition and was subsequently reviewed in the Critic:

We like the strong, stern countenances of these veritable heroes, men who worked ill the trenches, and who fought in that November morning in that bloody field of Inkerman. Their faces are deeply stained by the sun glare, and their whole appearance is more savage than is customary with the Guards while they are here in barracks...Mr Cundall's photographs are honest and "untouched."

The photographs were an attempt, perhaps at the Queen's commission, to aid the public in their search (or redeeming virtues in the Crimean War. Cundall and Howlett's photographs depicted common soldiers as national heroes who fought under the adverse conditions of the Crimea and emerged triumphant in spite of the incompetence of the the leaders. Holdgate's photogravure is an important example of the technology that permitted the wide dissemination of photographs and this representation also demonstrates the emergence of a new kind of military hero, the common soldier.

John Alfred Vinter

Sergeant Mins, Coldsteam Guards, Crimea, c. 1855

This color lithograph of a soldier killed in the Crimea was originally part of a set of four, the three others being of Sergeant Robins, Sergeants Troke, Rackley aud Long and Drummers Price and Watkins. The series of lithographs, entitled Vinter's Coldstream Guards, was published on February 2, 1856 by the printseller Henry Graves. The lithographers Day and Sons were well known for their images of the Crimean War. In 1854 they sent William Simpson to the Crimea to sketch the war, and twenty three large views made from sketches by him, M. and N. Hanhart and Lieutenant Mansell were reproduced as lithographs.

It is not certain whether the present lithograph was executed from a live portrait sketch or from a previous portrait. The reason for the execution is quite evident. During the Crimean War the Patriotic Fund was established to give financial support to the widows and orphans of Crimean veterans. This lithograph was sold in a special art auction for the benefit of this fund. The overwhelming support for the Patriotic Fund evidenced the new respect for the soldiers in the Crimea.

D.J. Pound after John and Charles Watkins

The Right Honorable Viscount Ranelagh, Lieutenant Colonel,

South Middlesex Rifle Volunteers c. 1865

The Volunteer Force was founded in 1859 as a result of the threat of invasion from France, since Britain's various commitments abroad meant that fewer than half of the army's soldiers were ever home at one time. It played a large role in improving the public's attitude towards the soldier. As its inception, the Volunteer Force was almost entirely midd1e-class. Yet, it soon drew from all classes, as the social standing of the sitter in this photogravure shows. Reproduced from a photograph by the brothers John and Charles Watkins, this print was originally part of a series of steel engravings published as a supplement to the Illustrated News of the World between 1859 and 1861. This particular engraving was number twenty of twenty-one in the second series of engravings, published from July to December of 1861, entitled Drawing Room Portrait Gallery of Eminent Personages.

Thomas Heron Jones Ranelagh (1812-1885), 7th Viscount, K.C.B., is depicted seated, his left arm draped over the back of his chair, his right hand casually resting upon his right knee. His relaxed three-quarter length pose, transcribed directly from the photograph, shows the informality resulting from the camera's ability to capture the sitter faithfully.

John and Charles Watkins had a studio in London in the 1860s, producing ethnographic prints as well as portraits. D.J. Pound executed most of his portraits after photographs by John Mayall. Although the Cataloque of Engraved British Portraits of the British Museum lists almost one hundred portraits by Pound, little is known about him.

Anonymous Photographer

Henry Stephan Walker, XIII Regiment of Hussars, c. 1865

Henry Stephen Walker purchased his commission as cornet in the XIII Hussars in November

1863 and as Lieutenant in 1867; he served in Canada from 1866 until 1869, and retired

in 1870. In the photograph we see the use of the props that had often been included in

similar painted depictions, with the soldier leaning against a chair in front of an

elaborate curtain. It was inevitable that, since no specific precedents existed for

photographic portraiture, elements would be borrowed from the closest ancestor: military

portrait painting. The transcription is not entirely successful: the camera captures the

sitters' images without idealization, but a staged atmosphere prevails.