Contributed Scholarship

Other Garibaldi panoramas and dioramas: Gompertz and Hamilton

Marcella Sutcliffe, University of Newcastle, UK

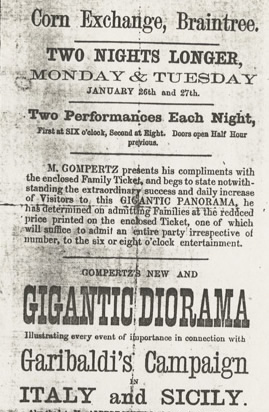

In 1861 a number of Garibaldi panoramas circulated in British provincial towns. While impresario Gompertz secured the Scottish audience in Edinburgh, by showing the ‘Garibaldi Campagn in Italy’ in the Waterloo Rooms (The Era, 28 April 1861), another Garibaldi panorama had been shown at the Music Hall in Leicester (The Era, 10 March 1861) and Hamilton’s Garibaldi panorama travelled between the northern provinces of Leeds (The Era, 24 February 1861) and Newcastle-upon-Tyne (The Era 24 March 1861 and 8 May 1861).

Radical Newcastle-upon-Tyne had a long and close association with Garibaldi, who, in 1854 had personally visited the town. The memory of the visit colored local political perceptions of the revolutionary so that Garibaldi’s depoliticized image, which gained popularity throughout the UK in 1860, was not so readily accepted by the Newcastle audience – contentiously divided, since the organizing of the British Legion, into two camps, radical supporters and conservative opposition.

While, no doubt, Hamilton intended to capitalize on the coverage of the debate on the Newcastle press, in March 1861 the impresario had a new challenge: for once, ‘the commercial success’ of his panorama, embedded in the image of a depoliticized hero, could not be ‘assured’ (Hyde, 2004).

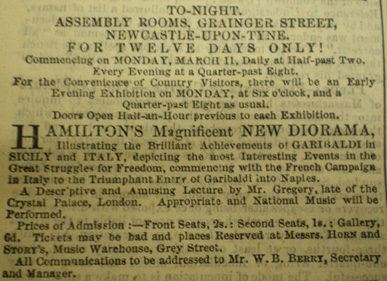

In advertising the panorama on the radical paper, Northern Counties Advertiser and Daily Chronicle, Hamilton used a marketing ploy: he published for three consecutive days (5-7 March) an announcement stating ‘Garibaldi is coming’…Newcastle-upon-Tyne readers would have been forgiven for mistakenly taking this as an announcement for another visit of Garibaldi himself to their town! The mounting suspense came to a climax when on 11 March the announcement of the panorama was clearly stated – appearing in a number of newpapers (Newcastle-upon-Tyne Courant, Newcastle-upon-Tyne Daily Journal, Daily Chronicle, Weekly Chronicle).

Despite the suspense created by the advertising, the turnout on the first night was disappointing and the audience ‘not numerous’. Thereafter, the advertisement appeared regularly on conservative and radical papers, yet on 19 March the Daily Chronicle simply commented in measured tones that the panorama was ‘respectfully attended’.

On 1 April, Hamilton transferred the diorama to the Music Hall, addressing for the first time ‘the Nobility, Gentry and inhabitants of Newcastle-upon-Tyne’ which he intended to entice with a new marketing ploy. Hamilton claimed that the panorama had been an ‘immense success’, an account which hardly tallies with the Chronicle’s reviews. In an attempt to raise the stature of the occasion, Hamilton coupled the performance of the panorama with the patronage of Lieut.-Colonel Sir John Fife, a household name in Newcastle, which would entice the upper-classes in and around town. Along with the show, the popular ‘Splendid BAND of the Corps’ of the renowned First Newcastle-upon-Tyne Rifle Volunteers would attend. The need to raise the profile of the panorama ‘suggests that, indeed, the performance alone was not deemed to be sufficient to guarantee a sell-out’, despite it taking place on Easter Monday.

By May 1861, however, the divisions that had pinpointed the expedition of the British Legion in Newcastle were a thing of the past and Hamilton made the decision to return again to Newcastle, the town which considered Garibaldi to be an ‘adopted son of Tyneside’ (Jackson, 2001). (Revised extract from the paper, Marcella Pellegrino Sutcliffe, ”Negotiating the ‘Garibaldi moment’ in Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1854-1861)”, winner of the ASMI Graduate Prize 2008).