Contributed Scholarship

Ugo Bassi

by Angela De Benedictis (Professor of Modern History, University of Bologna)

Part 1

«If ever Italy comes to be united may God restore her the Voice of Ugo Bassi. When Rome had fallen, when nothing was left for me but exile hunger and misery, Ugo Bassi did not hesitate a moment to accompany me. The name of Ugo Bassi will be the match-word of the Italians on the day of vengeance!!» Giuseppe Garibaldi, as quoted in the Panorama lecture of the “Heroic life and career of Garibaldi”.

This passage appears in the section of the script accompanying the Panorama, immediately following the general recapitulation of its scenes (Panorama Lecture - Image 129). It is here that the name of Ugo Bassi, one of the “martyrs” of the Risorgimento, is mentioned for the first time in the manuscript, together with an almost word-for-word quotation from the commemorative discourse that Garibaldi pronounced in 1859, ten years after Bassi’s death (the discourse is transcribed by Didaco Facchini in his Biografia di Ugo Bassi, Bologna, Zanichelli, 1890, II ed. riv., facsimile edition: Bologna, Forni, 1981). The image of Ugo Bassi, however, makes an earlier appearance, in scene 18 of the panorama, representing Garibaldi defending Rome. We recognize him in the figure of the priest who appears to the left of Garibaldi (in relation to the observer), positioned slightly in the background, behind the group of people shown aiding a wounded or dying soldier.

Ugo Bassi was indeed a man of the church. He had been a member of the Barnabiti order since the age of seventeen (he was born in Cento, near Ferrara, on August 12, 1801): to be precise, from October 24, 1818 to April 1848. On April 15 of that year, pope Pius IX signed a decree expelling Bassi from the order. The decree was issued by the pope whilst under great pressure by the numerous detractors who were accusing Bassi of heresy in order to stop him from inciting the people to take up arms and liberate Italy from foreign rule. Bassi was well known throughout the peninsula for his activity as a preacher, that he passionately practiced in Bologna and elsewhere out of love for both Christianity and his homeland, Italy. His endeavor in the fight for the liberation of Italy had begun in the Spring of 1848, when it still seemed that the pope wanted to position himself at the head of the national movement. Bassi had been appointed military chaplain in the pontifical army. However, after Pius IV’s promulgation of an encyclical refusing to wage war on Austria, Bassi had left Bologna and followed the army of volunteers who instead held the war to be indispensable. The encounter between Ugo Bassi and Garibaldi took place on April 4 1849, the day after Bassi had been nominated chaplain of the Italian legion commanded by Garibaldi. From then on, Bassi was often at the side of the general fighting against the French. He remained with Garibaldi and assisted him during the escape from Rome, until he was taken prisoner by the Pope’s gendarmes near Comacchio, on August 4 1849.

The author of the panorama has portrayed Bassi dressed in an cassock more similar to that of an Anglican priest (above all the collar) than to that of a father of the Barnabiti order (as one can see, for example, in the portrait by G. Raimondi, P. Ugo Bassi, 1849, reproduced in C. Collina, M. Gavelli, O. Sangiorgi, F. Tarozzi, eds., Ugo Bassi metafora verità e mito nell’arte italiana del XIX secolo, Bologna, Museo Civico del Risorgimento, 1999, p. 80). The script highlights Bassi's "apostolic" heroism and powerful preaching for the cause: “He was present at all the Battles and all acts of devotedness, he acted as a sister of charity, an apostle and was an intrepid soldier...His powerful eloquence not only raised the Italians to the love of Italy and a devotion for her, but it drew from the most rebellious coffers [sic] numerous and rich offerings. At Bologna the rich gave money by thousands: the women gave their Jewels their ring and their earrings. One young girl having nothing to give him cut off her magnificent hair and offered to him [sic]”(Panorama lecture - image 130).

Two paintings from circa 1850 show the effects of Bassi’s powerful eloquence in soliciting the people of Bologna to offer their personal possessions for the common cause: the first (shown here to the left) by Napoleone Angiolini depicting Ugo Bassi On the Steps of San Petronio. And the second (shown on the next page of this essay) by Gaetano Belvederi, which portrays Ugo Bassi at the Pia Column, in Rome.

Two paintings from circa 1850 show the effects of Bassi’s powerful eloquence in soliciting the people of Bologna to offer their personal possessions for the common cause: the first (shown here to the left) by Napoleone Angiolini depicting Ugo Bassi On the Steps of San Petronio. And the second (shown on the next page of this essay) by Gaetano Belvederi, which portrays Ugo Bassi at the Pia Column, in Rome.

Part 2

Just as the author of the script opens the sorrowful reminiscences of Garibaldi with a reference to the awe-inspiring voice of Ugo Bassi, he closes it with the same evocative image: “Garibaldi thus speaks of his friend Ugo Bassi ‘His powerful word fascinated the people and if God had marked a term to the misfortunes of Italy, the voice [of] Bassi, like that of St. Bernard, might have drawn whole populations to the field.’ " (Panorama lecture - Image 130) .

.

In the same years, pope Pius IX was considered responsible for a large number of Italy’s misfortunes, the pope who had initially made Italian patriots believe that they had his support in the fight for independence. But disillusionment had already settled by April 29 1848, with the encyclical addressed to the Assembly of Catholic Bishops. On January 1 1849 disillusionment became dread. Pius IX had issued another encyclical (the so-called Monitorio) which called for the excommunication of all those who were in favour of the Constituent Assembly established in Rome on December 29 1848, with the accusation of having affronted the temporal authority of the Pope. The threat of excommunication, as is known, was a spiritual arm often used by the popes in order to obtain results on the level of temporal power. Pius IX therefore continued a tradition which prided itself on a series of illustrious antecedents and in this manner he discouraged both those who had placed faith in him and those who feared the effects of excommunication (See: David I. Kertzer, Prisoner of the Vatican, The Popes' secret plot to capture Rome from the new Italian state, Boston : Houghton Mifflin, 2004; some Renaissance examples in A. De Benedictis, Abbattere i tiranni, punire i ribelli. Diritto e violenza negli interdetti del Rinascimento, in «Rechtsgeschichte. Zeitschrift des Max-Planck-Instituts für europäische Rechtsgeschichte», 11, 2007, pp. 76-93). In order to reassure those who were frightened by the “gravity of the harm” constituted by excommunication, Ugo Bassi wrote the dialogue Della scomunica e più altre cose de’ tempi nostri (Bologna, Tipografia Tiocchi, 1849, pdf). The literary genre of the dialogue was particularly well suited to his objective. To the terror expressed by the interlocutor Giorgio, Ugo responded with an abundance of arguments in order to demonstrate that one could not be excommunicated without committing a sin or without being culpable of something; that striving for the liberty of one’s Lombard or Venetian “brothers” was not a culpable offense; that it could not have been the Pope to decide to unleash the threat of excommunication on his followers and "sons," but instead that he had been forced into the decision by the “wolves” of the Roman senate and by the King of Naples who was holding him prisoner in Gaeta (on November 23 1848, Pio IX had fled Rome for Gaeta); that the Pope should go to war against the “Germans” in order to defend his followers and all of the Italians; that the Constituent was in no way an act of rebellion versus the Pope, but instead nothing more than “a gathering or general assembly of a great number of deputies who, elected through free vote and nominated by the people, converged from all the communities of the state in Rome in order to discuss the governance of the state and the war against the Germans, since everything moves in the name of this cause.” Throughout the dialogue Ugo Bassi repeated his conviction that it had not been Pius IX to want the excommunication of his people: “Excommunicate a population would be to sow anarchy and civil war.” And in conclusion he declared himself confident that the Constituent would have called the Pope again, but “in the remarkable condition of declaring war on Austria and of liberating Lombardy and Venice.” Otherwise (“if not”), there would remain no other solution: “let’s go, let’s go with Christ: He said: my Kingdom is not of this world … He said: As I gave my life for you, in this way, give your lives for your brothers.”

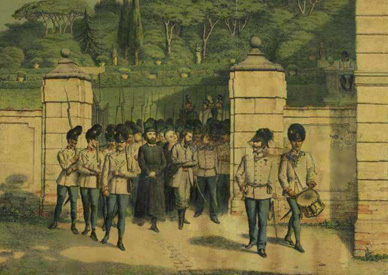

For his Italian brothers Ugo Bassi gave his life. On August 4, 1849 he was captured in Comacchio by gendarmes of the State of the Church, a day after having arrived in the vicinity with Garibaldi and other fugitives from Rome. On August 6, he was transferred to Bologna by the Austrians, who had captured the city again after having been driven away by the popular uprising of August 8 1849. Ugo Bassi was executed on the same day, August 8, 1849, four days before his forty-ninth birthday (as shown in this anonymous litograph of 1860).

For his Italian brothers Ugo Bassi gave his life. On August 4, 1849 he was captured in Comacchio by gendarmes of the State of the Church, a day after having arrived in the vicinity with Garibaldi and other fugitives from Rome. On August 6, he was transferred to Bologna by the Austrians, who had captured the city again after having been driven away by the popular uprising of August 8 1849. Ugo Bassi was executed on the same day, August 8, 1849, four days before his forty-ninth birthday (as shown in this anonymous litograph of 1860).