How do maps allow us to access, interpret and understand Hell? Or, as one sixteenth-century author put it, to “see Hell before our eyes?”

![Dialogo di Antonio Manetti, cittadino fiorentino, circa al sito, forma & misure dello Inferno di Dante Alighieri poeta excellentissimo [Dialogue of Antonio Manetti, Florentine Citizen, Concerning the Site, Form and Measurements of the Inferno of Dante Alighieri, Most Excellent Poet]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D15_AEON900m.jpg)

Girolamo Benivieni (1453–1542)

Florence, Italy: Filippo Giunti, c. 1510

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

First published in 1506

![Dialogo di Antonio Manetti, cittadino fiorentino, circa al sito, forma & misure dello Inferno di Dante Alighieri poeta excellentissimo [Dialogue of Antonio Manetti, Florentine Citizen, Concerning the Site, Form and Measurements of the Inferno of Dante Alighieri, Most Excellent Poet]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/YC-M31md.jpg)

Girolamo Benivieni (1453–1542)

Florence, Italy: Filippo Giunti, c. 1510

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

First published in 1506

![Comento di Christophoro Landino Fiorentino sopra la Comedia di Danthe Alighieri Poeta Fiorentino [Commentary by Florentine Cristophoro Landino on the Comedy of Dante Alighieri Florentine Poet]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/olio002115.jpg)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Florence, Italy: Nicolo di Lorenzo della Magna, 1481

Brown University Library, Annmary Brown Memorial Collection

Engravings by Baccio Baldini after Sandro Botticelli; marginal annotations throughout with at least one early hand

![Dante col sito, et forma dell'inferno tratta dalla istessa descrittione del poeta [Dante with the Site, and Form of the Inferno Based on the Description of the Poet]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D13_AEON899m.jpg)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Venice, Italy: Aldo Manuzio and Andrea di Asola, 1515

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

![Dante, La divina commedia novamente corretta spiegata e difesa da F.B.L.M.C. Cantica I [The Divine Comedy Newly Corrected, Explained and Defended by Francesco Lombardi]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/Dxx-83_AEON2774_1791-1m.jpg)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Rome, Italy: Antonio Fulgoni, 1791

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

Engravings based on the 1568 edition of Bernardino Daniello’s commentary

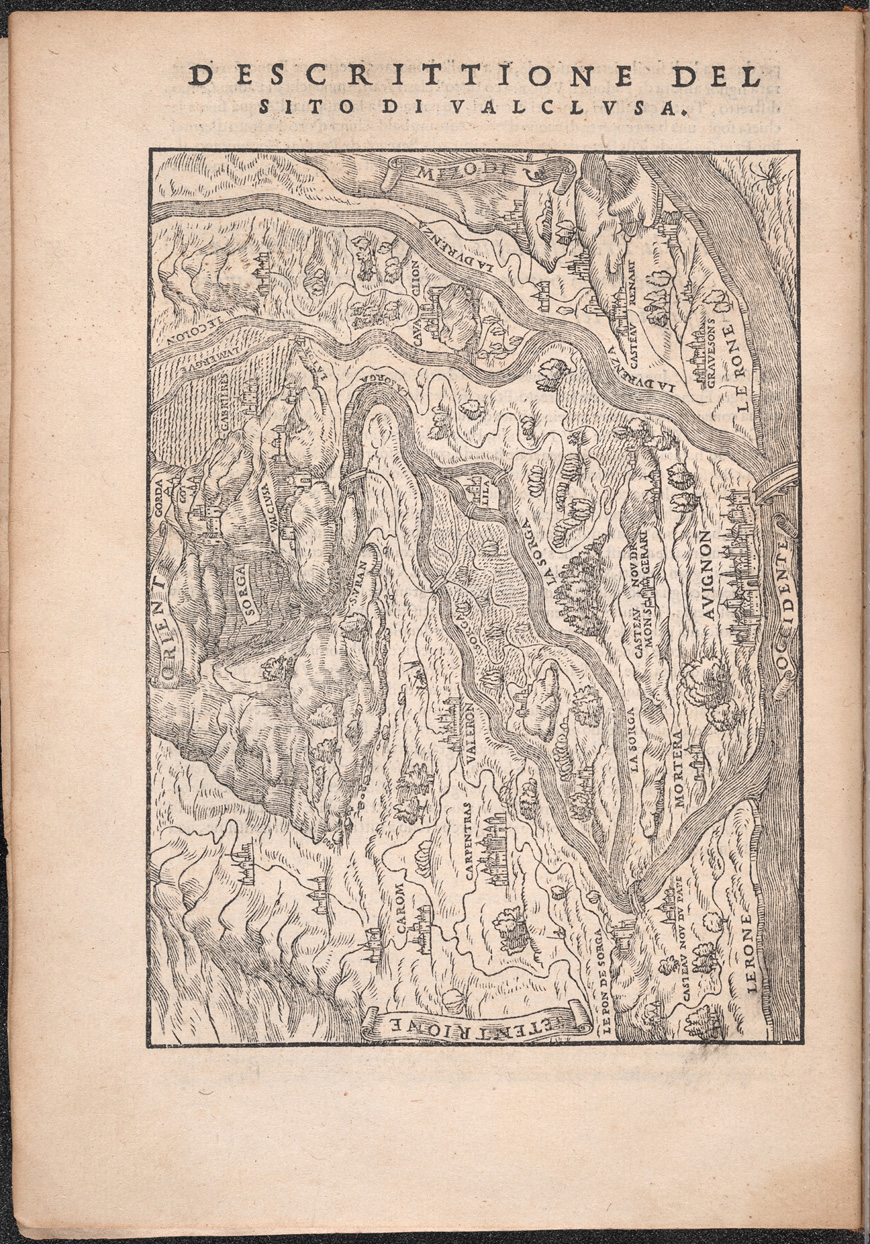

Francesco Petrarca (1304–1374)

Venice, Italy: Gabriele Giolito, 1547

Brown University Library, Hay Star Collection

Ptolemy (active second century)

Rome, Italy: Pietro della Torre, 1490

BUL, Annmary Brown Memorial Collection

The coat of arms of Agostino Patrizi Piccolomini, Bishop of Pienza and Montalcino (1483–1496), is painted on the left side of the world map. The other arms are to the recipient of the volume, possibly Alfano Alfani

Florentine mathematician Antonio Manetti is considered the first person to have measured Hell. His calculations were illustrated in a volume published by the Giunti family of printers of Florence in seven woodcuts, the first maps of Dante’s Inferno in print (1, 2). These maps inspired a visual tradition upheld by the poem’s modern editions.

Starting with the Comedy’s first illustrated printed edition in 1481 (3), artists, editors and publishers employed different printing techniques and styles to illuminate Dante’s Inferno. Maps helped readers more easily grasp the complex moral, philosophical and geographical structure of Dante’s poem, while reflecting the richly cartographic nature of his writing. The poet’s own detailed descriptions of cities, countries, mountains, monuments and bodies of water oriented readers to Hell’s topography. Dante also assigned precise mathematical dimensions to the lowest circles of Hell, sparking a debate among Italy’s most illustrious thinkers about the underworld’s geography.

Through the circulation of atlases, travelogues, chronicles and globes, sixteenth-century readers could experience worlds both real and imagined. A field of renewed interest in the early fifteenth century, cartography offered another way to situate literary landscapes in the natural world. Indeed, as the author of the 1506 edition argues, readers should consult maps and seafaring charts to accurately navigate the poem’s geography. Comparing maps in editions of Dante (4, 5) and Petrarch (6) to contemporary maps in print (7) reveals how the Comedy might have been interpreted through cartography and speaks to the dialogue between geography and literature in the 16th century. Maps also illuminate how cartographical interpretations of the poem began to shore up Dante’s authority in scientific culture.