The Art School Down the Hill

November 7, 2013 by lelgin | Comments Off on The Art School Down the Hill

Brown University and Rhode Island School of Design are within steps of each other, so it’s no surprise that the two have a great deal of overlap in the community. While my full time work is as a photographer at Brown, I have taught photography at RISD (also my alma mater) in their Continuing Education department since 2002. I often use examples from my work at Brown to talk about lighting, lens selection, and other photographic techniques. I was advisor to RISD|CE’s digital photography certificate program for ten years, and during that time I would bring students to Brown to view our studio setup, and talk about the safe handling and digitization of cultural heritage materials.

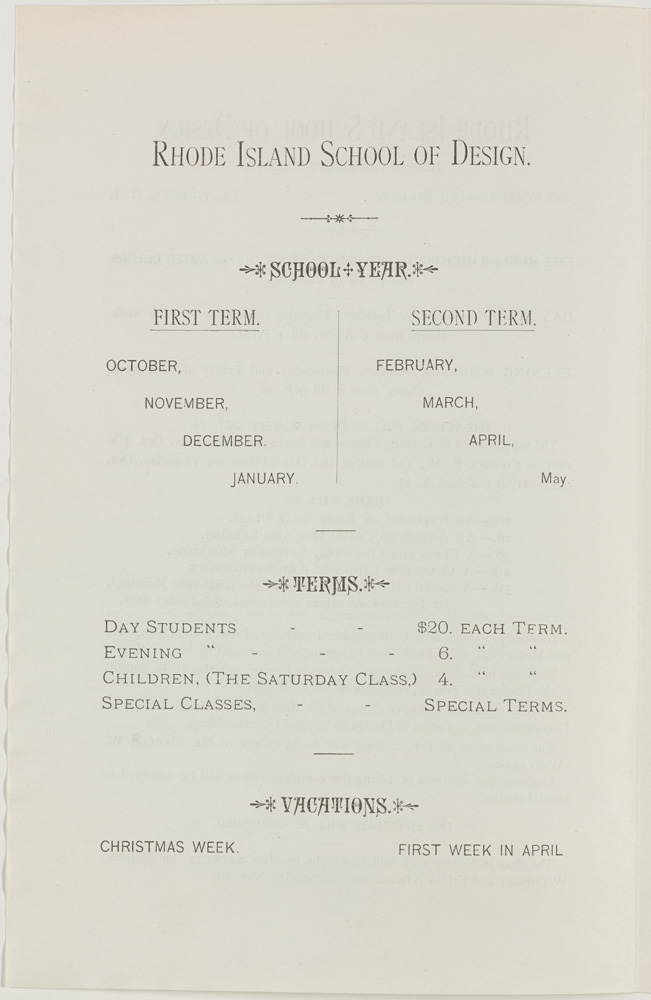

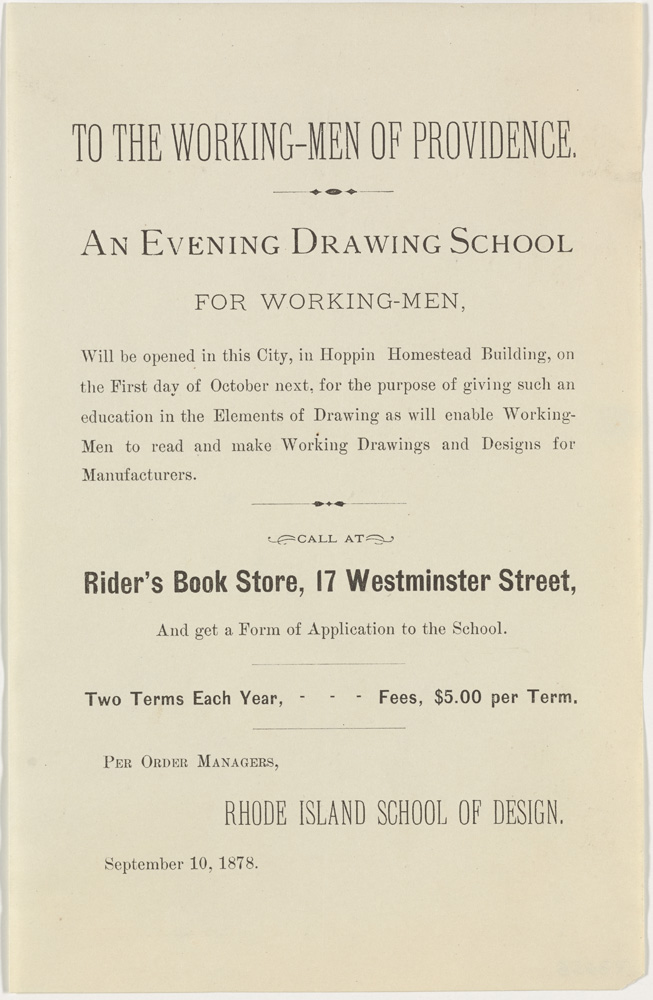

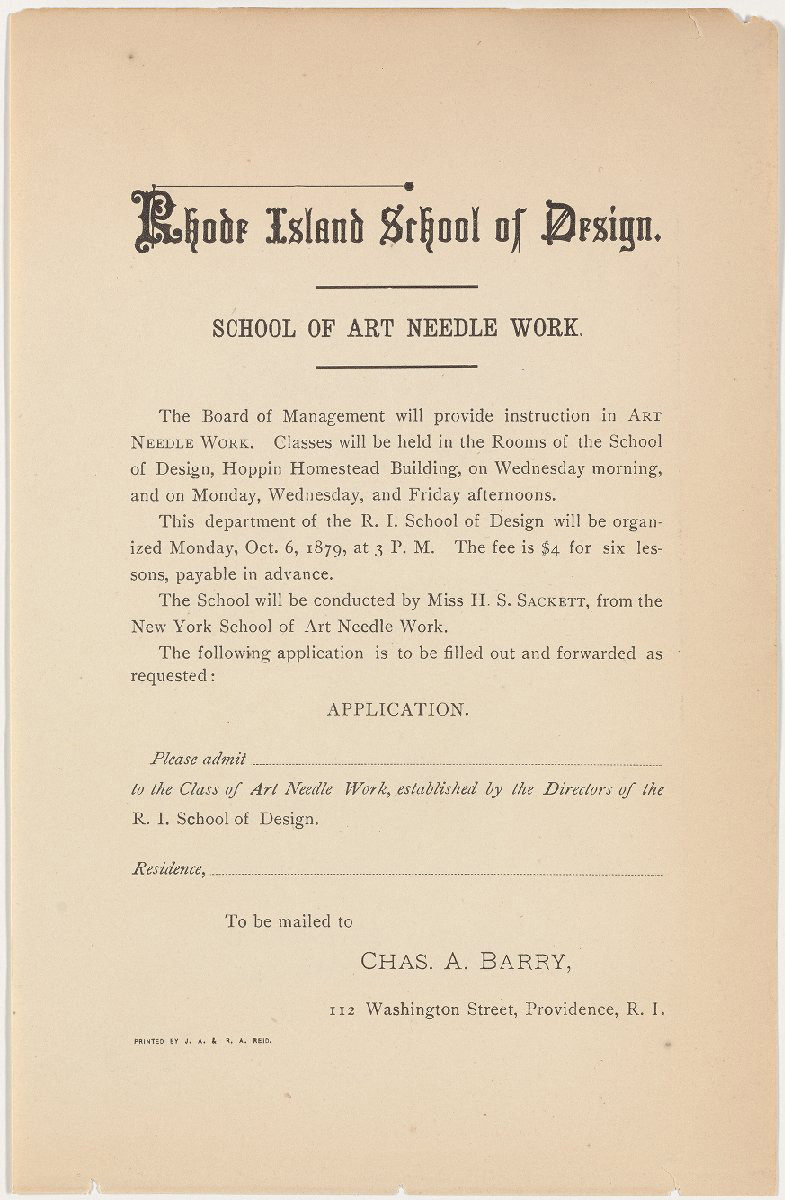

It is due to my personal connection to RISD and RISD|CE that I was so excited to come across materials over a century old from RISD while photographing at Brown. I’ve been working on digitizing broadsides from the late 1800s, and have found several items from RISD, including bulletins introducing their evening drawing courses for men, art needle work courses for women, listings of their daytime, evening, and youth course schedules, and even an application to the school. As we continue to work our way into the turn of the century, I’m hoping we find even more.

The RISD bulletins are part of the Rider Broadsides collection, which contains a wide range of books, pamphlets, manuscripts, broadsides, ephemera, scrapbooks and newspapers from the 17th through the early 20th centuries. Named for the collector, Sidney S. Rider, Rider Broadsides is the largest private collection of Rhode Island-related materials, and we expect this digitization project to keep us busy for the better part of the academic year.