Illuminating Postcards

February 13, 2013 by lelgin | 2 Comments

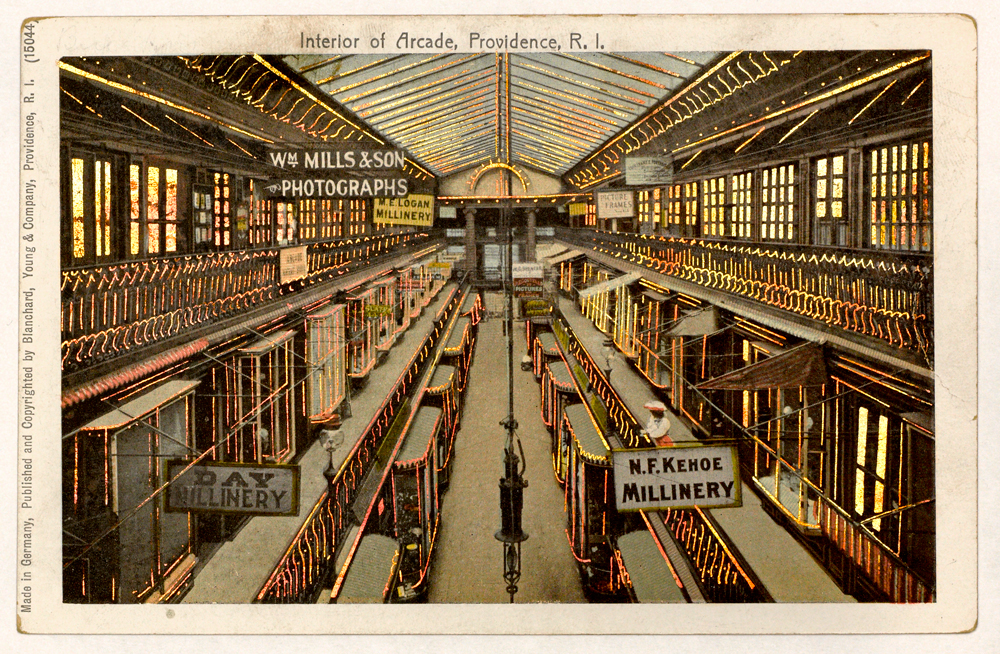

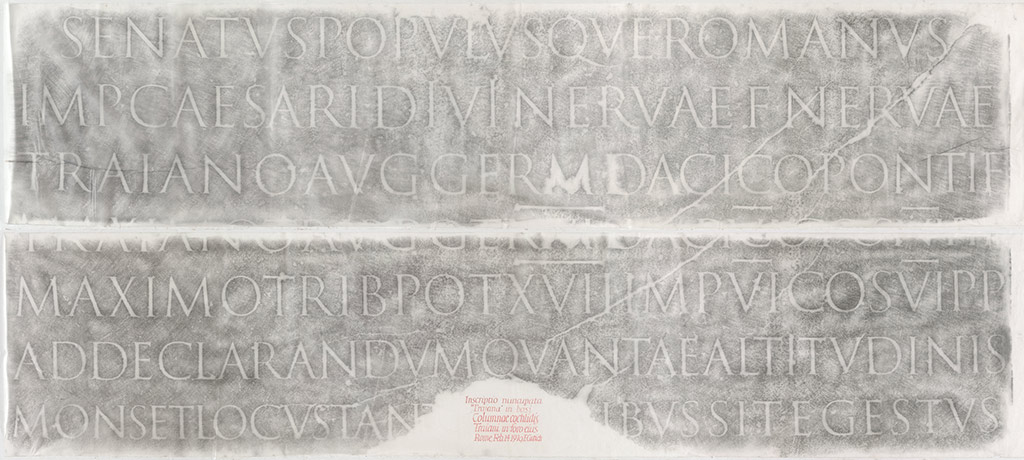

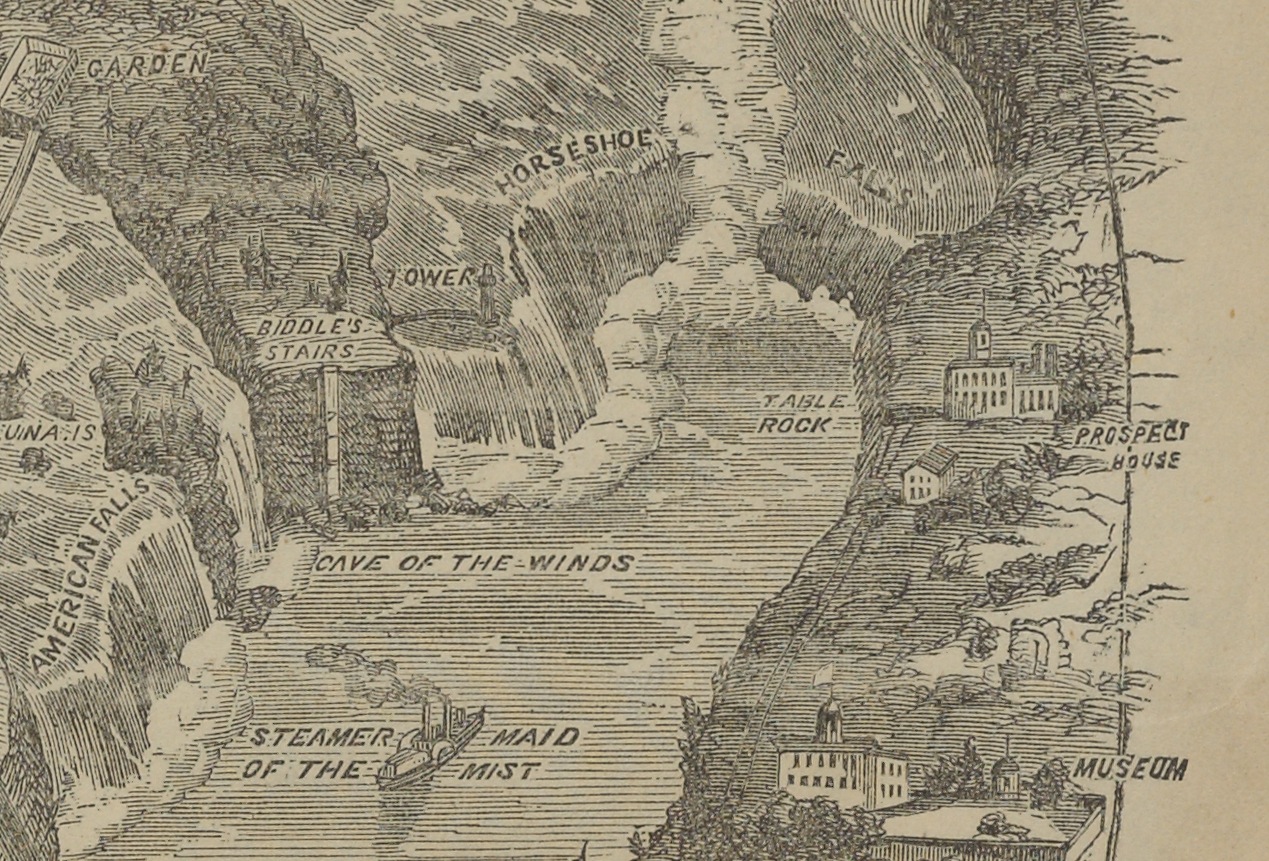

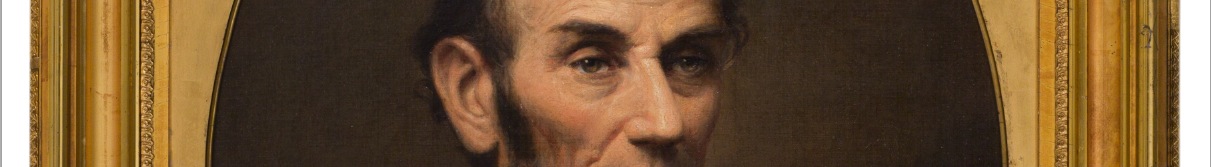

While I generally work with objects and texts from Brown’s Special Collections, I also work with images for the instructional image collection with Karen Bouchard, the Scholarly Resources Librarian for Art and Architecture (she has a Twitter feed for the Brown Imaging Blog). These are images scanned for faculty members (primarily in History of Art and Architecture and Visual Art). For this project, I was digitizing postcards in the personal collection of Brown alumnus Seth Cohen, lent to Professor Dietrich Neumann for use in his lectures. These postcards – representing a range of locations and time periods – look at first like ordinary postcards, but illuminate in specific areas in the card when backlit. Sometimes, the backlighting shines through windows and doors in a bright, copper color; other times, the light brings forth a part of the image unseen when viewing normally.

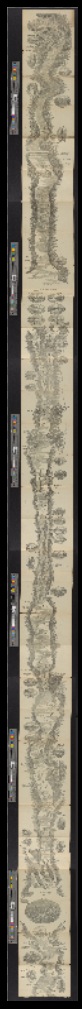

The following are two animations of illuminated postcards: they start with the postcard lit normally, then move to two different strengths of backlight.

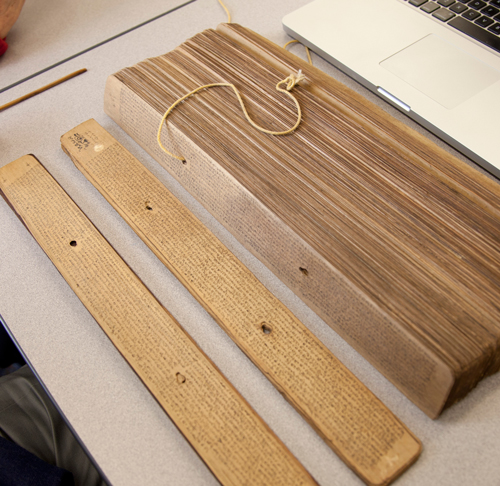

While it’s relatively easy to view one of these postcards – holding them up to a window or to a bright indoor light does the trick – capturing that in a photograph is much more challenging. After some trial and error, I devised a simple system to backlight the postcards with a light strong enough to show the layers of information, while still providing enough ambient light to read the information on the front of the card. I set up our Leaf Aptus II-12 digital back on its medium format camera, attached it to a tripod set to shoot straight down, and did tethered capturing into Capture One (the software we use to capture using our Leaf digital back). I used two Canon 580EXII flash units; one mounted on the hot shoe of the camera, and one functioning as a synched flash on the floor with a Gary Fong Lightsphere diffuser. I used an acrylic box to lay the postcards on, and put that on some boxes so that there would be some room between the flash on the floor and the postcards. I bounced the flash on the camera off the ceiling, so that it would provide a diffused ambient light that would neither overpower the postcards, nor cancel out the backlighting.