Digitizing the “mirror with a memory”

October 7, 2014 by lelgin | Comments Off on Digitizing the “mirror with a memory”

As we celebrate Brown’s 250th anniversary, Digital Production Services has been asked to digitize many historical university materials. Some of the earliest photographs in the university’s extensive collection are daguerreotypes made of graduating classes, and I was recently asked to digitize two these: the class of 1847; and the class of 1852.

The common reflective characteristics of a daguerreotype.

Daguerreotypes present several challenges in digitization, mainly due to their inherent physical characteristics. Above all else, daguerreotypes are by their very nature incredibly reflective. In this nineteenth century process, the actual photographic image is formed on a silver-coated copper plate that is polished to a mirror-like sheen. Depending on the lighting and viewing angle, even just hand-holding the daguerreotype may provide you with a clear image of the subject, or you may just be staring back at yourself. Additionally, daguerreotypes are often encased behind glass to protect the fragile image resting on the surface of the silver – helpful in maintaining image integrity, but adding another layer of reflection. In order to view the daguerreotypes (as well as digitize them) with any degree of success, you must control the lighting that strikes the object, and completely block out any object that would cause a reflection. Because lighter objects are always more visible in this type of reflective image, photographing a daguerreotype of any size requires surrounding the object with black foam, paper, or cloth that will help offset its reflective properties.

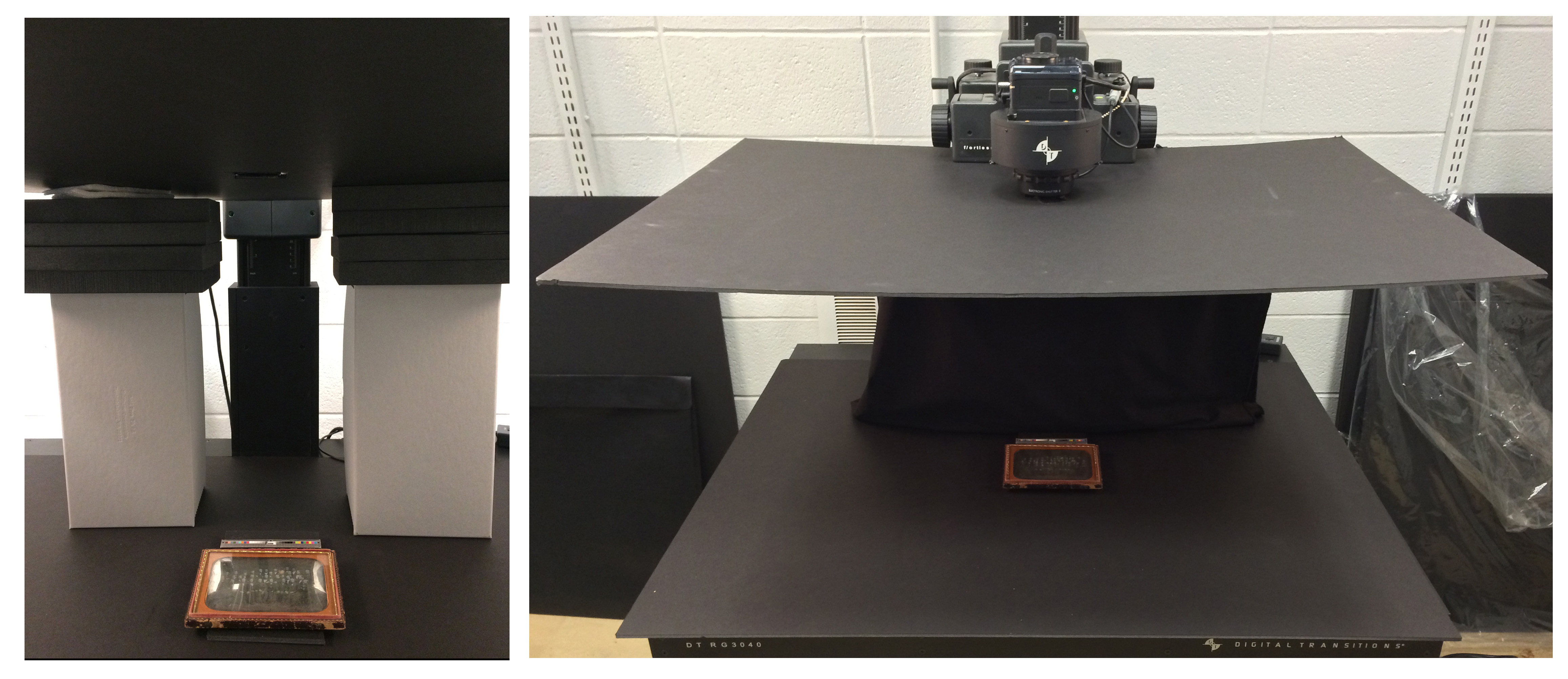

I approached photographing these daguerreotypes the same way I would approach any reflective material: by building what amounts to a tent around the object. Whereas with many objects (highly reflective silver with no printing, for instance) work best surrounded by white paper or foam core (or even semi-translucent vellum), daguerreotypes work best surrounded by all black. Black eliminates reflections, as well as helps make the image on the surface of the silver as clear and readable as possible. The most obvious reflection is often that or the camera itself; since I was photographing the daguerreotype reprographically, the camera was positioned directly above that polished silver surface. The best way to avoid seeing the camera’s reflection in the lens is to take a large sheet of black foam core, cut a small hole just for the lens of the camera, and cover the entire camera rig with the foam core.

Daguerreotype, Brown University, class of 1852: The image on the left shows the camera (with its various wires to the computer and strobes) directly reflected in the daguerreotype; the image on the right shows the same daguerreotype with the camera covered by black foam core.

Although it’s possible to just use a sheet of black foam core to reduce reflection, I built a small rig to hold the foam core up (hand holding it myself could potentially add camera shake) and reduce any reflections from the walls behind the camera (painted a light neutral grey, but still reflective). These photographs show the supports for the foam core and the hole I made for the lens, and then the final setup for shooting.

Additionally, although proper focus is always important, it is particularly important when it comes to daguerreotypes. Daguerreotypes were developed in 1839, and these older processes required much longer exposure times than what we are used to: a typical exposure could last up to a minute or more. Because of this, at the time it was challenging to keep people in focus because it was difficult to keep them still; as a result, it can be tricky to make out faces due to the motion blur. Thus, when digitizing, keeping the focus as sharp as possibly is necessary to producing a readable image. For this daguerreotype, I actually placed the object on several blocks of foam core to focus into the encasement and reach the image on the plate beneath.

Finally, both daguerreotypes are suffering from degradation and corrosion, common problems for this sensitive and fragile type of photograph. They will soon be sent to the Northeast Document Conservation Center for conservation and repair.