Within thirty years of its completion, the library in Manning Hall had outgrown its capacity of 30,000 volumes. As early as 1852, the Library Committee had described the “absolute incapacity of Manning Hall to meet the existing needs of the Library.” President Ezekiel Robinson complained that “the Library was so crammed with books two and three deep on the shelves, that only the librarian could find what was wanted.” Even so, the library served as the primary scholarly resource and even inspiration for faculty and students. As Benjamin Ide Wheeler, later President of the University of California, wrote while a Brown student:

The library with its thirty-eight thousand books made a profound impression on me. Its mysterious alcoves lined to the high ceilings with delicately matched volumes whose backs proclaimed their worth; the boxes of cards on the window — seats which, written in the noble calligraphy of the librarian presented an array of titles opportunities for learning such as my eye had never seen.…the story of the rare editions and wonderful collections which the librarian was glad to tell, even to freshmen — all these combined to make the library in my eyes by far the most dignified and worshipful department of the college.

Brown University Library, later Robinson Hall (Built 1875–1878).

Brown University Library, later Robinson Hall (Built 1875–1878). Biblia Sacra Polyglotta (London: Sumptibus Samuel Bagster, 1831).

Biblia Sacra Polyglotta (London: Sumptibus Samuel Bagster, 1831). University Library (Robinson Hall).

University Library (Robinson Hall). Providence Franklin Society, Catalogue of plants, Collected by the Botanical Department of Providence Franklin Society, Principally in Rhode-Island, 1844. Arranged by S. T. Olney (Providence: Printed by Knowles and Vose, 1845).

Providence Franklin Society, Catalogue of plants, Collected by the Botanical Department of Providence Franklin Society, Principally in Rhode-Island, 1844. Arranged by S. T. Olney (Providence: Printed by Knowles and Vose, 1845).Crowded conditions and admiration notwithstanding, there was to be no new library until John Carter Brown’s bequest in 1874 of a plot of ground at the corner of Prospect and Waterman Streets, along with $50,000 for the new building. Sophia Augusta Brown, his widow, added the balance required so that the entire project, estimated at $120,000, was contributed by the Brown family.

At its dedication, in early 1878, Librarian Reuben Aldrich Guild carried the first book into the new building, a copy of Samuel Bagster’s Polyglot Bible (London, 1831) which was described as “the book of books, the embodiment of true wisdom, and the fountain head of real culture, civilization and moral improvement.” The library’s architects, Walker and Gould of Providence, designed the new library building (later named Robinson Hall in 1946) in the fashionable Venetian Gothic style popularized by John Ruskin. The structure, one of the nation’s most innovative library buildings for its time, bore a close resemblance to Princeton’s newly-completed Chancellor Green Library, with its cruciform floor-plan and central reading room lighted from a rotunda and 600 gas lights. Three octagonal wings projecting from the rotunda contained 72 alcoves, each fitted with movable shelves. Although no rare book room was set aside in the new library, special rooms were included to house large illustrated books, engravings, paintings, and pamphlet literature. The new library’s capacity was 150,000 volumes and the University was confident that it would suffice for “generations to come.” Within 20 years it would be filled to overflowing.

This remarkable and unexpected growth came about because the library’s finances improved and because it continued to receive gifts both of individual books and, increasingly, of large book collections. In 1879, the library was given the first of a series of endowments established by bequest. Col. Stephen T. Olney, a prosperous Rhode Island manufacturer and distinguished amateur botanist, bequeathed his collection of 700 books, 500 in the field of botany, to Brown along with $10,000, the income from which was to strengthen the library’s botanical holdings. The collection, described by Guild as “rare and costly, and in expensive bindings” was placed in a dedicated alcove of the library.

Other library endowments were added in the years immediately following the establishment of the Olney Fund. Professor J. Lewis Diman was memorialized by a $10,000 fund established by his former students and by “ladies who were members of Professor Diman’s private classes.” Professor William Gammell, who had earlier served as Librarian for a year, bequeathed $10,000 to the library in 1889. The income was to be used to purchase books in United States history.

The Kammavācā (Painted and lacquered manuscript palm leaves, 18th century).

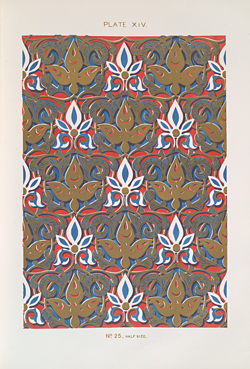

The Kammavācā (Painted and lacquered manuscript palm leaves, 18th century). Owen Jones, Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra (London: O. Jones, 1842–1845).

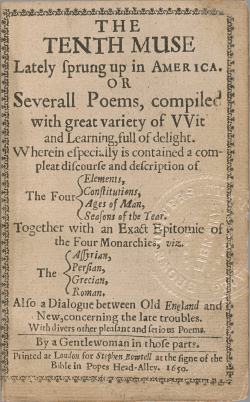

Owen Jones, Plans, Elevations, Sections, and Details of the Alhambra (London: O. Jones, 1842–1845). Anne Bradstreet, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (London: Printed for Stephen Bowtel, 1650).

Anne Bradstreet, The Tenth Muse Lately Sprung Up in America (London: Printed for Stephen Bowtel, 1650).Many of Brown’s most important books continued to arrive as gifts. The following examples illustrate the variety of 19th century gifts and a growing appreciation of the rarity of many of these gifts. In 1881, the Rev. Dr. Josiah Nelson Cushing, Class of 1862, presented one of the most exotic, a complete set of the Tipitaka, the canonical text of Buddhism. The Rev. Dr. Cushing was a missionary to the Shan people of British-occupied Burma and a noted linguist who translated the Bible into the Shan dialect and compiled a Shan-English dictionary. Because the Buddhist priesthood opposed the alienation of their sacred writ, the Rev. Dr. Cushing obtained the manuscripts surreptitiously and smuggled them to the United States. Some of the manuscripts, those described by Cushing as “having the bright gilding, and vermillion covers, come from Mandalay, where the art of palm leaf book making flourishes in its greatest perfection.” Others, he wrote, were old books that had “long been used in monasteries.” Upon their arrival, the manuscripts were placed in the security of the print room. Today, the manuscripts remain in pristine condition and many are among the library’s most beautiful artifacts.

From the bequest of Joseph J. Cooke, a Providence native who had made his fortune in the California gold rush, the library acquired 1,300 volumes which Guild described as “the largest and most valuable” addition to the library since the days of Jewett. Cooke bequeathed $5,000 to Brown to enable it to buy books from his collection, sold at auction in 1883 and 1884. Among the many rare books included in that purchase were the Bible printed by John Baskerville (Birmingham, 1769), Guillaume du Bartas’s Divine Weekes and Other Workes (London, 1641), the first English translation of Euclid’s Elements of Geometrie, printed by John Day (London, 1570), and an illuminated Flemish Book of Hours (circa 1400). An unusually large number of finely illustrated books were obtained through the Cooke bequest, examples being Diego Saavedra y Fajardo’s The Royal Politician Represented in One Hundred Emblems (London, 1700), and John Guillim’s A Display of Heraldry (London, 1679), plus several extra-illustrated titles including William Hazlitt’s View of the English Stage (London, 1818). The most expensive item purchased at the Cooke sale was Owen Jones’s Alhambra (London, 1842–1845) at $360.

Also in 1884, the library received the Harris Collection of American Poetry and Plays. Begun by Albert Gorton Greene, Class of 1820, expanded by Caleb Fiske Harris, Class of 1834, and bequeathed to Brown by Senator Henry Bowen Anthony, Class of 1833, the Harris Collection had long been renowned as one of the largest and most important collections of Americana in private hands, its aim being to collect every printed work of American and Canadian poetry and drama from colonial times onward. When left to Brown, the number of books totaled almost 6,000 volumes. Recognizing its importance, the library placed the collection in a specially secured room, where over the next 20 years it would be joined by other books identified as rare. The Harris Collection was Brown’s first major special collection in the modern sense and the Harris Room the library’s first specifically designated rare book room.