Page 41

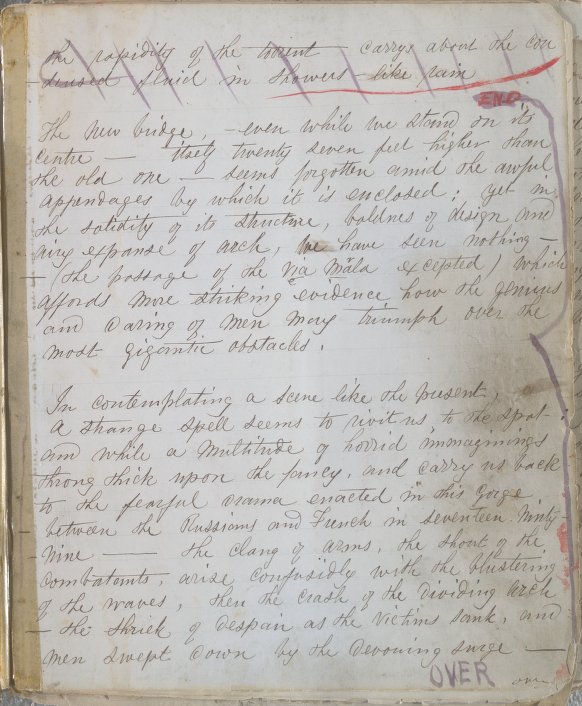

the rapidity of the torrent carrys about the con

densed fluid in showers like rain.

The new bridge,—even while we stand on its

centre—itself twenty-seven feet higher than

the old one—seems forgotten amid the awful

appendages by which it is enclosed: yet in

the solidity of its structure, boldness of design and

airy expanse of arch, we have seen nothing —

—(the passage of the via mala excepted) which

affords more striking evidence how the genius

and daring of men may triumph over the

most gigantic obstacles.

In contemplating a scene like the present, a

a strange spell seems to rivit us to one spot:

and while a multitude of horrid immaginings

throng thick upon the fancy, and carry us back

to the fearful drama enacted in this gorge

between the Russians and French in seventeen ninty-

nine—the clang of arms, the shout of the

combatants, arise confusedly with the blustering

of the waves, then the crash of the dividing arch

—the shriek of despair as the victims sank, and

men swept down by the devouring surge—