Turning Point

“VICHY IS DESERTED, BUT SAFE. NO TRAINS FOR SEVERAL WEEKS YET, AND NO MONEY.”

-Mme. Alexander-Marias, August 9, 1914.

In June of 1914, before beginning her freshman year at the Women’s College, Sarah (“Sally”) Ida Morse boarded the “S.S. Winnifredian” in Boston, bound for Liverpool and a tour of the British Isles. By the time she returned to Providence in late August, she had witnessed war declarations, in both London and Paris, that marked the beginnings of a collapsing Europe and a changing world.

A scrapbook11. BUA. SB-M9 Morse, S.I. (1918) vol. 1. BUA also holds a scrapbook that Morse compiled during 1918. SB-M9 Morse, S.I. (1918) vol. 2 that Morse compiled to document her travels, offers us a glimpse inside that world from the privileged perspective of a student at the Women’s College at Brown University. Aboard the Winnifredian, Morse dined at the Captain’s table and received letters from home. One letter advised that “people who become seasick can be cured by living on champagne and ginger snaps.” Another instructed her not “to fall in love with an English lord, for whom you would be eternally bored, nor yet give one heed to an English Earl, not one is fit for an American girl.” Arriving in Liverpool on June 29th, 1914, Morse may have seen newspaper reports on the assassination the previous day of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie, as their motorcade wound through the streets of Sarajevo.

In what seems like a haunting gesture today, Morse purchased a postcard of the Lusitania. The following May the ship will be torpedoed by a German U-Boat as it nears Liverpool. Sinking in 18 minutes with a loss of 1,962 lives, the attack will be regarded as a pivotal moment in America’s eventual engagement in the war.

Morse, joined by her aunt Rosa, began their tour around the British Isles by attending garden parties and high teas, and then visiting Stirling castle, guided by a “a Scotchman half-soused.” After sailing down the River Clyde to Loch Striven, they toured Edinburgh Castle and Seymour Street. They drove thru Ribble Valley, visited Whalley Abbey and attended the opera. In Paris, they spent time at the Louvre and Versailles. While there, Germany declared war against France. Morse and her aunt witnessed the mobilization of French troops to cheering crowds. After returning to London in early August, they shopped at Selfridges, and attended musicals. Morse and her aunt were in London when England declared war against Germany, and this time witnessed British troops marching in the streets.

While staying with her cousins in Lancashire, Morse received a letter from the American Consulate in Manchester advising that “all Americans in the district, whether already registered or not, appear in person and have themselves registered upon the proper forms at this consulate.” Another letter arrived, this from desperate friend in France, dated August 9th. Mme. Alexander-Marias wondered if Morse might ask her cousin to send her some French notes, explaining “All people having letters of credit are absolutely penniless, which is my case. [ ]…The situation is certainly serious, even English gold can not be exchanged easily, if I had some. You know the anxiety of my country and you may imagine my bleeding heart! Thank god dear old England had found out we were oppressed and has come to our rescue, so we are hopeful!”

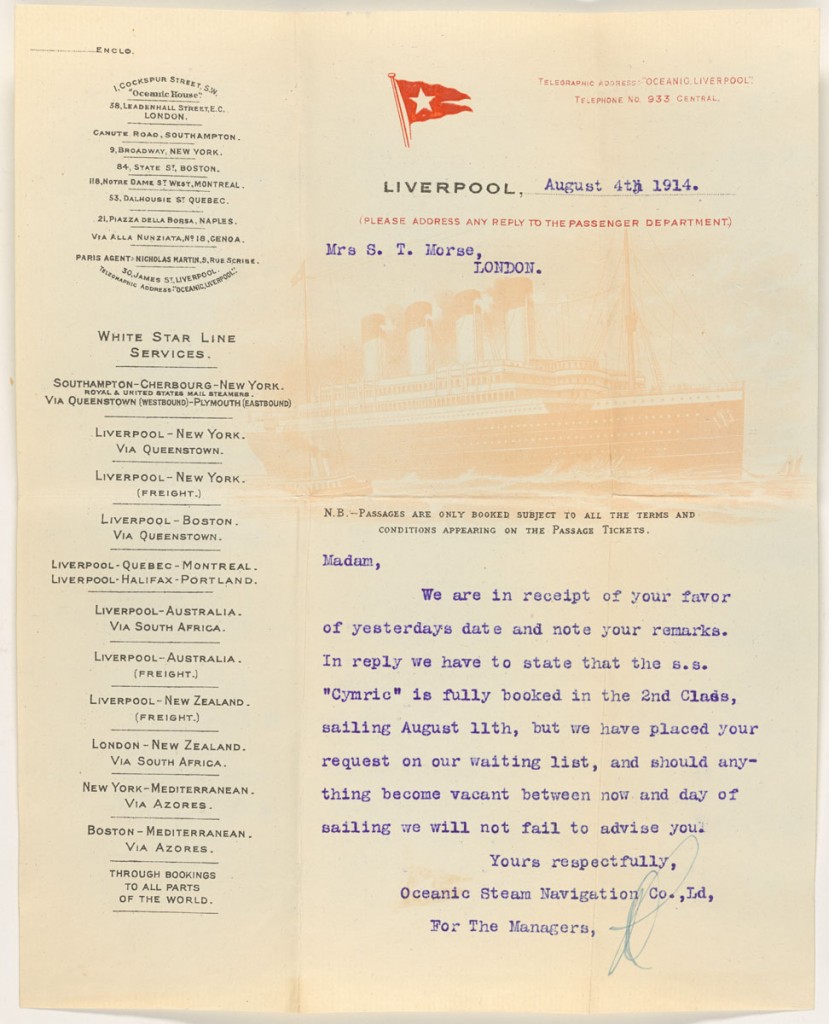

For their return voyage, Morse and her aunt had been booked on the “Arabic” due to sail on August 24th, but England’s declaration of war prompted them decide to return home earlier. They changed their booking to the “Winnifredian,” scheduled to sail on August 14th, but the ship was taken over by the Government. Morse wrote to the Leyland Line offices requesting passage on the “Cymartic,” but was informed that it was fully booked. Morse noted on the telegram’s envelope “Nothing doing.” After writing home for money and expressing her concerns, Morse received a letter from her mother, who counseled “I do not think you need to be alarmed about getting home as the U.S. Government is getting busy to help all the stranded tourists to return. [ ]..so don’t get rattled and fool away all this good money for nothing. The Germans will all be killed by Aug. 25th.”

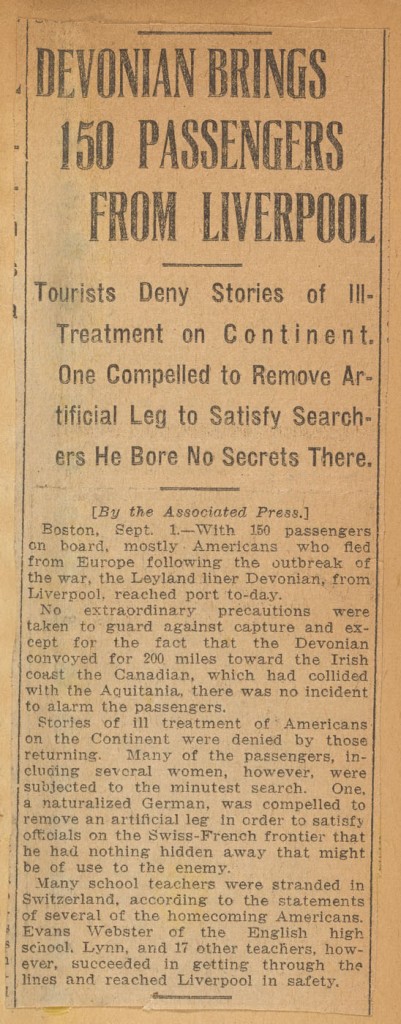

Morse and her aunt finally secured passage on the steamer, “S.S. Devonian,” and departed for Boston on August 22nd. Two days out of Liverpool, a collision between two ships, the “Aquitania” and “Canadian,” occurred. The Devonian accompanied the damaged Canadian back to port in Queenstown. After diverting to the Newfoundland Banks to avoid “hostile interruption,” followed by four days of severe storms, the Devonian finally arrived in Boston on August 31st.

Although Morse witnessed declarations of war, in both Paris and London, and watched as soldiers marched off to combat, it was not these events that made the strongest impression. Back in Providence, she reported to local newspapers that the most exciting part of the trip was the collision of the two ships at sea. A few weeks later, on September 9th, direct effects of the conflict Morse saw erupting in Europe were felt on Brown’s campus, when the death of Professor Henri F. Micoleau at the first battle of the Marne was reported. The world would be at war for the remainder of Morse’s college years.

- BUA. SB-M9 Morse, S.I. (1918) vol. 1. BUA also holds a scrapbook that Morse compiled during 1918. SB-M9 Morse, S.I. (1918) vol. 2

Places mentioned in this story:

Providence, Rhode Island; Boston, Massachusetts; Liverpool, England; Blackpool, England; Worthing, England; Ribble Valley, England; Stirling, Scotland; Glasgow, Scotland; Edinburgh, Scotland; Blackburn, England; Paris, France; London, England; Baxenden, England; Accrington, England; Saltcoats, Scotland; Vichy, France; Queenstown, Ireland; Grand Banks of Newfoundland