“GOODBYE, SCENES OF MY COLLEGE DAYS, AND PLEASANT MEMORIES OF OLD RHODE ISLAND.” –Robert Stetson McFarlane. February 1, 1918.

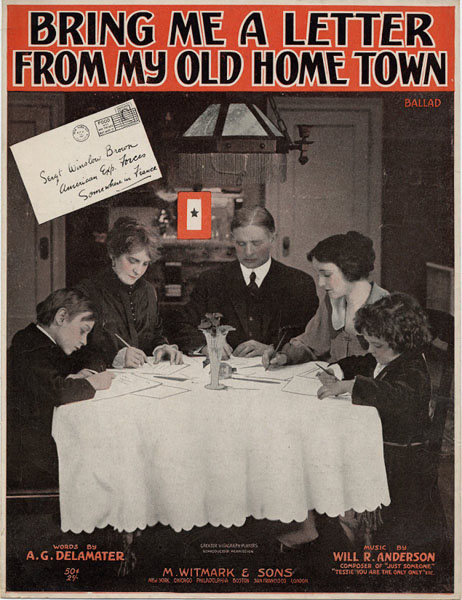

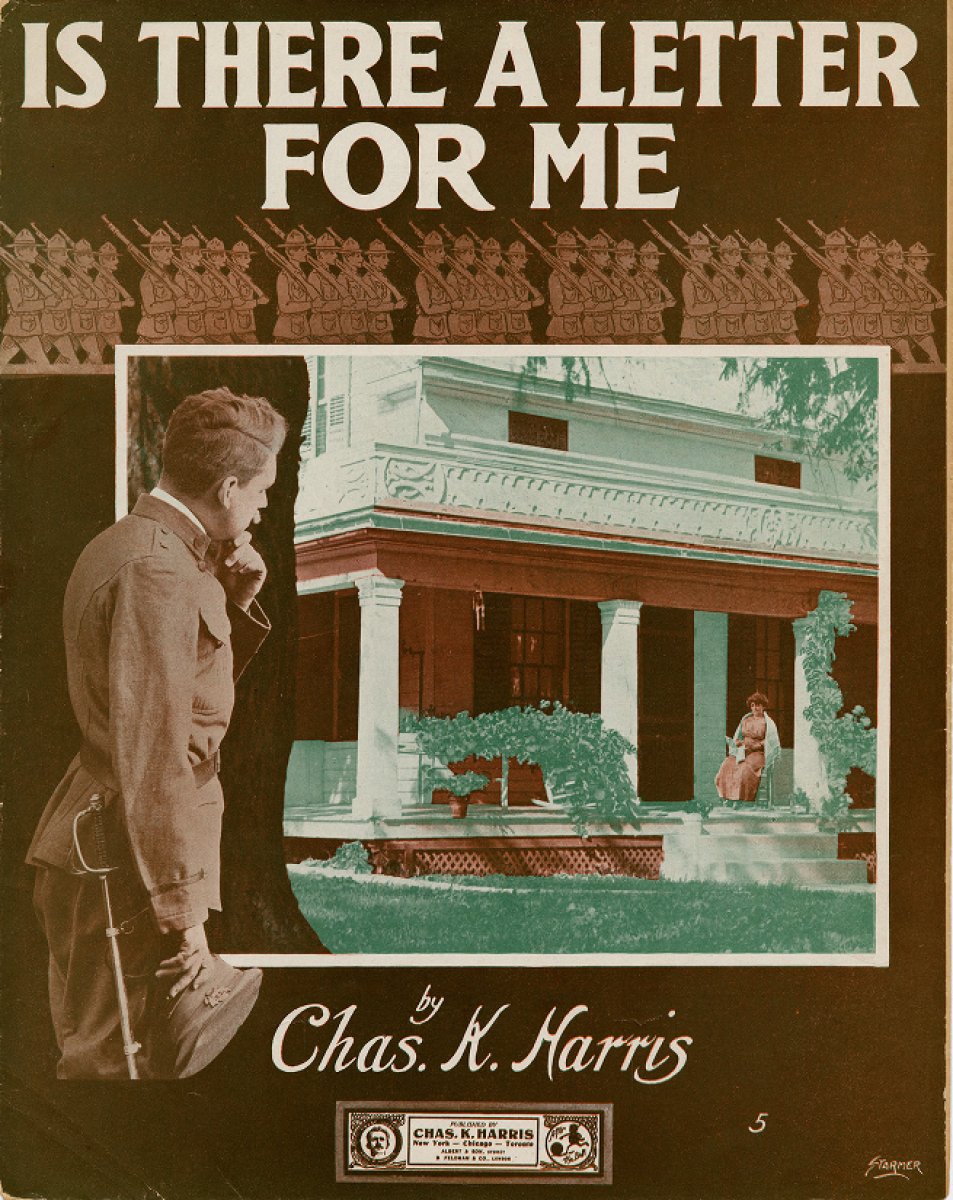

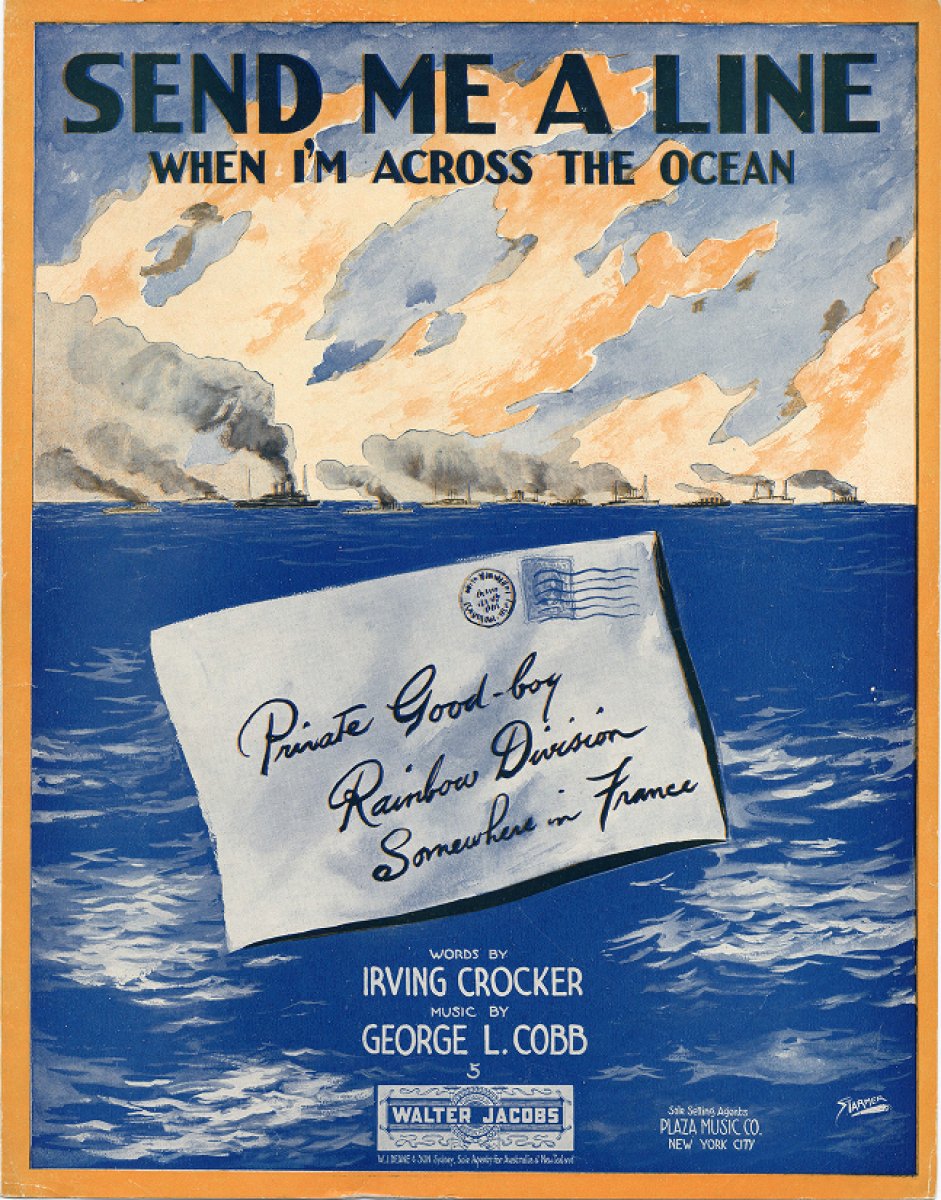

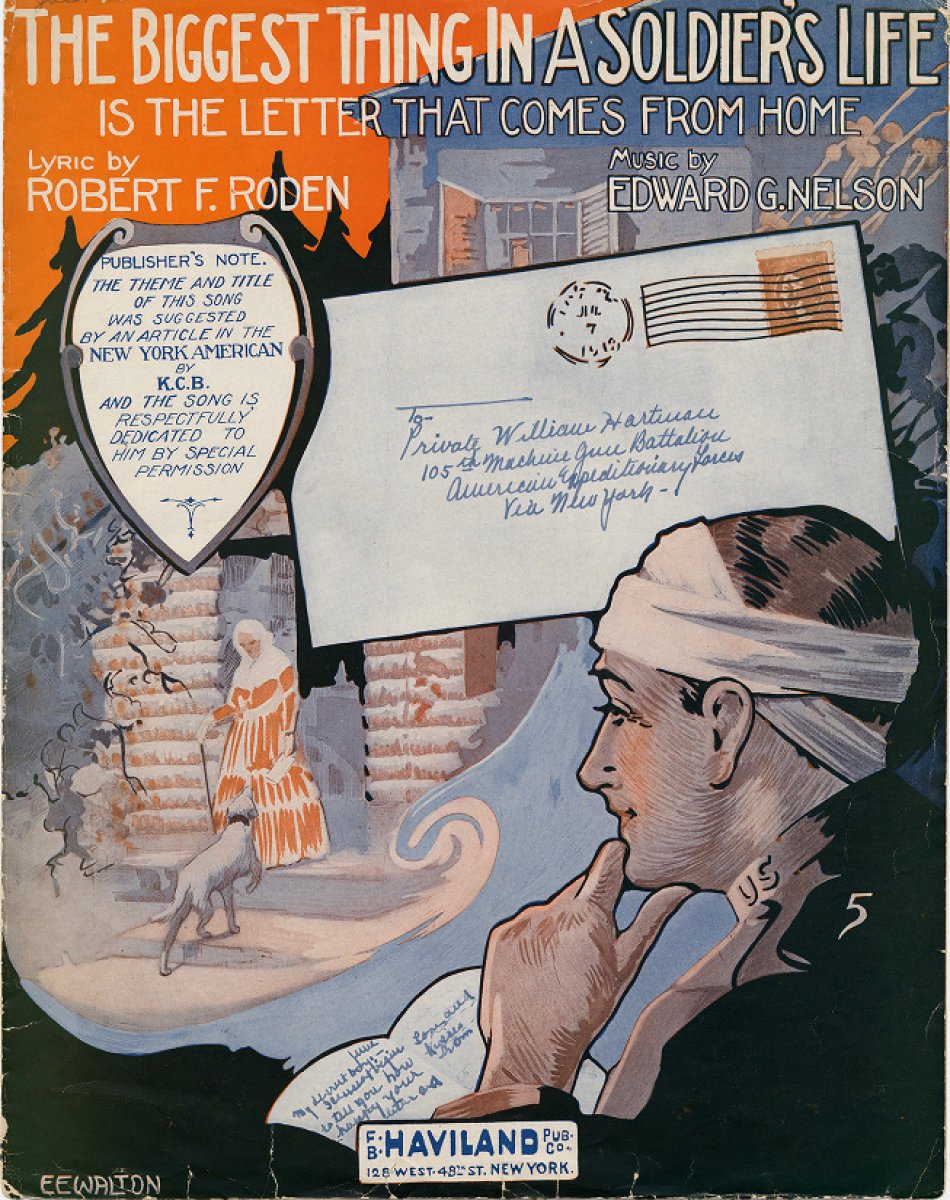

Throughout the duration of the war, President Faunce and faculty members across campus corresponded with Brown’s student, alumni, and faculty servicemen. Letters written by 274 of Brown’s servicemen, serving in the American Expeditionary Forces, or the Young Men’s Christian Association, comprise the World War I Correspondence collection, held in the University Archives. Additional letters and postcards are found in collections of faculty papers.

Many of the letters express pride for “the part Old Brown is playing in this struggle”[1. Charles Leslie Fairbanks Paull (1897 ) to W.H.P. Faunce, April 8, 1918] and the reliability of Brown’s servicemen, “the Brown men in this organization are dependable men. They are among the best in the battery.”[2. John Westley Rhoades (1917) to President Faunce, December 30, 1917] “Don’t have any fear! In the pinch Brown men will display their mettle.”[3. Kenneth Dewey Johnson (1919) to Dr. Faunce, January 10, 1917] Sentimental wishes to return to “dear Old Brown” and the serenity of its picturesque campus are frequently found in the letters. “I can imagine the front campus with the beautiful old elm trees, and over them, the new Service Flag with its three hundred bright stars.” [4. Raymond J. Walsh (1917) to Dr. Faunce, March 11, 1918] F. B. Harrington (1919) reported on the “childish homesickness” he and some other Brown men were experiencing for the campus, the Union, and college life.[5. BUA. BDH, January 3, 1918] The servicemen express gratitude for letters and packages sent from campus, and often plead for news of Brown. Sent from somewhere in France, somewhere in Belgium, or within the dugout, many of the letters are censored with passages or words carefully cut from the body of the text.

Earl Hammond Walker (1914) wrote to President Faunce from France on April 8th, 1918, “I first looked upon No Man’s Land, I could hardly realize that thing about which we had read so much about for the past four years was actually before my very eyes. Our men are falling into this game with a great deal of spirit. To see them in their dug-outs and in the trenches one would think that they had been brought up to this sort of life.” Albert Whitman Sweet (1911), a member of the Red Cross Sanitary Service, wrote to President Faunce on July 24, 1918 of the reception that his transport received in France, “Children lined the road for three miles as we disembarked from our ships. They gave us flowers and fruit and tagged along for a long distance. Many of them were in the care of sisters of the church and looked sad under their temporary cheer and joy. All of the adults I have seen here have had some mark of mourning.”

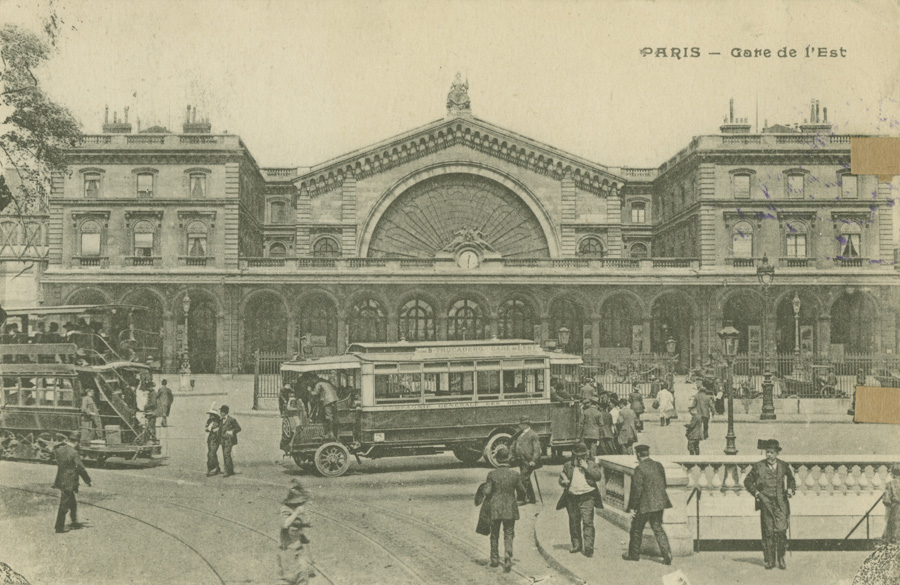

The letters contain many reports of the servicemen running into other Brown Men, hearing Brown songs, and meeting up with Brown men at the American University Union, at 8, Rue de Richelieu in Paris. “I’ve been over about 5 months, and nearly all of France, and yet at every port I seem to run into someone from the Hill.”[6. BUA. BAM, October 12, 1918. pg3] In a letter from Paris dated October 7th, 1917, Henry A. Batchelor (1917) informed President Faunce that “Jack Starrett told me a few days ago that he had heard a rumor going around college to the effect that I was dead – killed, I believe on a transport returning to France from Salenica. It gives me great pleasure to contradict this rumor as you can well imagine.”

Armand Laurier Caron (1918) wrote to his fraternity brother Ed about his not so favorable impressions of France. “La Belle France does not strike me so favorably, after all. [ ]…“France has not appealed to me any more lately, Ed, than it did in the beginning. That Statue of Liberty will never look so good to me as when I see it on my return trip, believe me.” William Hood Shupert (1922) wrote to Ed on July 23th, 1918. “I am now in a hospital as a result of being caught in a mustard gas barrage. My eyes were closed for about three days and I had a few minor body burns but now I am practically well. I was out in an observation post when it got me.” In a later letter dated August 16, 1918, Shupert enclosed a photograph and commented that it was “one I had taken to send to my mother as proof that I had not lost an arm as it was rumored in Ardmore.”

James M. Kent (1899) and Stephen S. Bean (1914) described the absence of young male civilians in France, noting about one male to every 25 females, and the frequent funeral processions.[7. BUA. BAM, April 1918. pg170-172] William Williams Keen (1859) a Major in the Medical Section and one of the oldest men in the service, having served also in the Civil War, wrote of his work “mitigating the widespread ravages of tuberculosis in France” and rehabilitating the civilian doctors of France and Belgium, who “when they return to their blighted homes, will have absolutely nothing except their willing hands and hearts.” Keen also wrote of the dangers facing the surgeons in the field, “never has there been so many casualties in the medical services – in this war, surgeons, while presumably classed as “non-combatants” share danger equally with the line officers. And they are not a whit behind the latter in bravery and devotion.”

George Robertson Douglas MacGregor (1891) wrote to Dean Randall that Jack Starrett (1916) was “so cheerful amid heartbreaking surroundings – He did not enjoy the hell of war – no one does – but shellfire or gas could not stop him from “Carrying on.” In January of 1918, Starrett was killed after his plane crashed on what was to have been his first cross country flight. Carroll Burton Larrabee (1918) described conditions on the ground, or rather in the muck, ”the combination means almost three feet of thick, clinging mud. This does not add to the joys of life. Leading a horse through such mud is not the greatest fun I can imagine. Nor is helping to drag a heavy field piece out of three or four feet of muck. But all such work does its part in getting us ready for the sterner work that is ahead of us.” Alongside the harrowing descriptions of life at the front-lines trenches, vivid descriptions of another sort are also found. Joseph B. Bowen (1915) wrote to President Faunce on July 1st, 1918. “You will remember the fields of deep red poppies on the continent. There is one rather poor hayfield here that is just a crimson flame from the air, and adjoining is a field of bright yellow buttercups. If people could see in a painting the brilliant riots of color we see from a plane, they would say the artist had lost his head.”[8. BUA. BAM, 19:5. December, 1918 pg99-100] Lieutenant Bowen was killed in action during an air battle with Fokker scouts in France on September 7th, 1918.

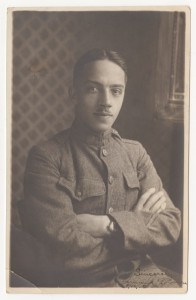

George W. Berriman (Non 1920) wrote home to his family from France on June 17th, 1918 informing them that “This is the last letter you will receive from me for a long time due to a military movement.” He goes on to report that “our stove (a hole in the ground covered with tin) was flooded and we had to go without breakfast. We managed a dinner of cornbread, turnips, and turnip-greens, but supper- – – well, it looks dubious.” On July 15th, Berriman was killed by a shell explosion in the trenches near Suippes on the Champagne Front. [Read transcriptions of Berriman’s letters.] Wheaton Carr Vaughan (1918) penned a note to his former biology professor, and the inventor of the circular letter Review Hints, H. E. Walter, “Dear “Doc” Walter – Believe me, I sure was glad to hear from you! It took me back to the old Biology “lab” with all its skeletons and peculiar odors! I could almost see the spineless amoeba and the colored crayons for making those diagrams of yours look like a futurist picture. Well I’m putting in some hard licks in the “big game” and expect to be “up there” by the time this reaches you. Sorry this picture isn’t much good but that face of mine is the only one I possess at present, and besides that inverted oatmeal dish doesn’t make one look very natural. I’ll do my best to send some part of the Kaiser back to you for use in the “lab.” Yours very sincerely, Wheaton Vaughan, 2/15/18.[9. BUA. MS-IUF-W1. H.E. Walters Papers, February 15, 1918]

Vaughan wrote to Walters again on June 16th, 1918. “I have been so busy tending to such business as dodging shells and putting on gas masks, etc. that I have had little time for letter writing. [ ]…We have just been lucky that’s all, I guess, but probably someday we will get ours, but here’s hoping! “France is certainly a beautiful country at this season of the year and one can hardly bring himself to believe that such hardship and loss of life is taking place daily, but the near-by explosion of a big shell soon dispells (sic) any such dream.” Vaughan went on to relay his company’s “great good fortune of having had only one man killed and another slightly wounded.” The good fortune Vaughan experienced eventually ran out. He died of wounds on November 11th, 1918, two hours after the Armistice was signed.

Related materials in the BDR