Charlie Steinman took a roundabout route to write his prize-winning paper, “Martin Luther’s whore more than a pope: Annotation, Disgust, and Materiality in the Reformation Reception of the Pope Joan Myth,” about a folio in the Nuremberg Chronicle. For his final project for Professor Tara Nummendal’s course “Age of Imposters: Fraud, Identity, and the Self in Early Modern Europe,” Charlie chose to write about “a medievalist who wasn’t real.” He decided on on Pope Joan, the central figure in a legend that arose in the 12th and 13th centuries about a woman, Joan, who masqueraded as a man, John, eventually becoming the pope, then blowing her cover upon giving birth during a papal procession.

“She was then either stoned to death or died during childbirth, depending on whether God or the cardinals were punishing her,” Charlie said. “The story varies.”

Charlie was intrigued by Joan because she was “not only an imposter, but an imposter whose existence was contested,” and he wanted to interrogate how the afterlife of this myth – it’s perpetuation into the 15th and 16th centuries – shaped discourse in the Reformation. He was particularly interested in how Reformers capitalized on Joan’s gender to discredit the Catholic church. The recycling of Joan’s story as anti-papal propaganda coincided with a period of tightening restrictions on women’s spirituality and canonization as saints. Charlie wanted to dissect how these presentations and restrictions influenced one another.

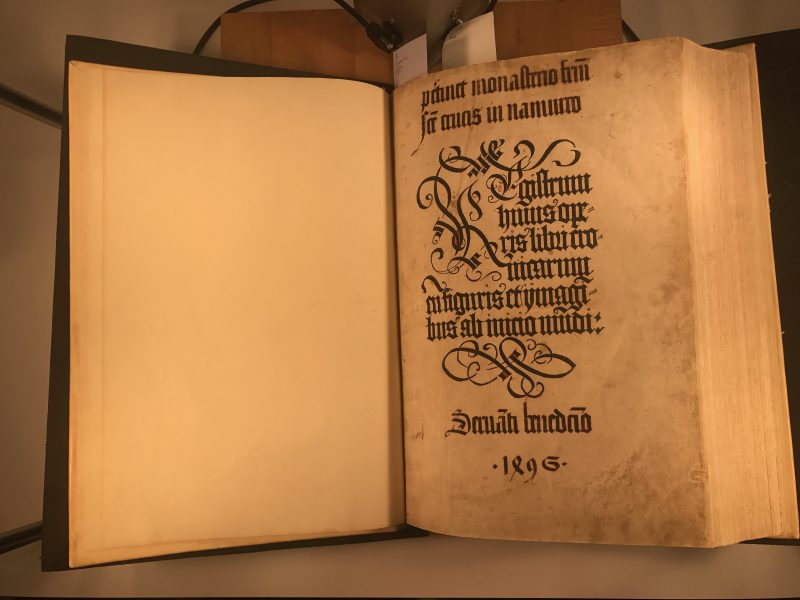

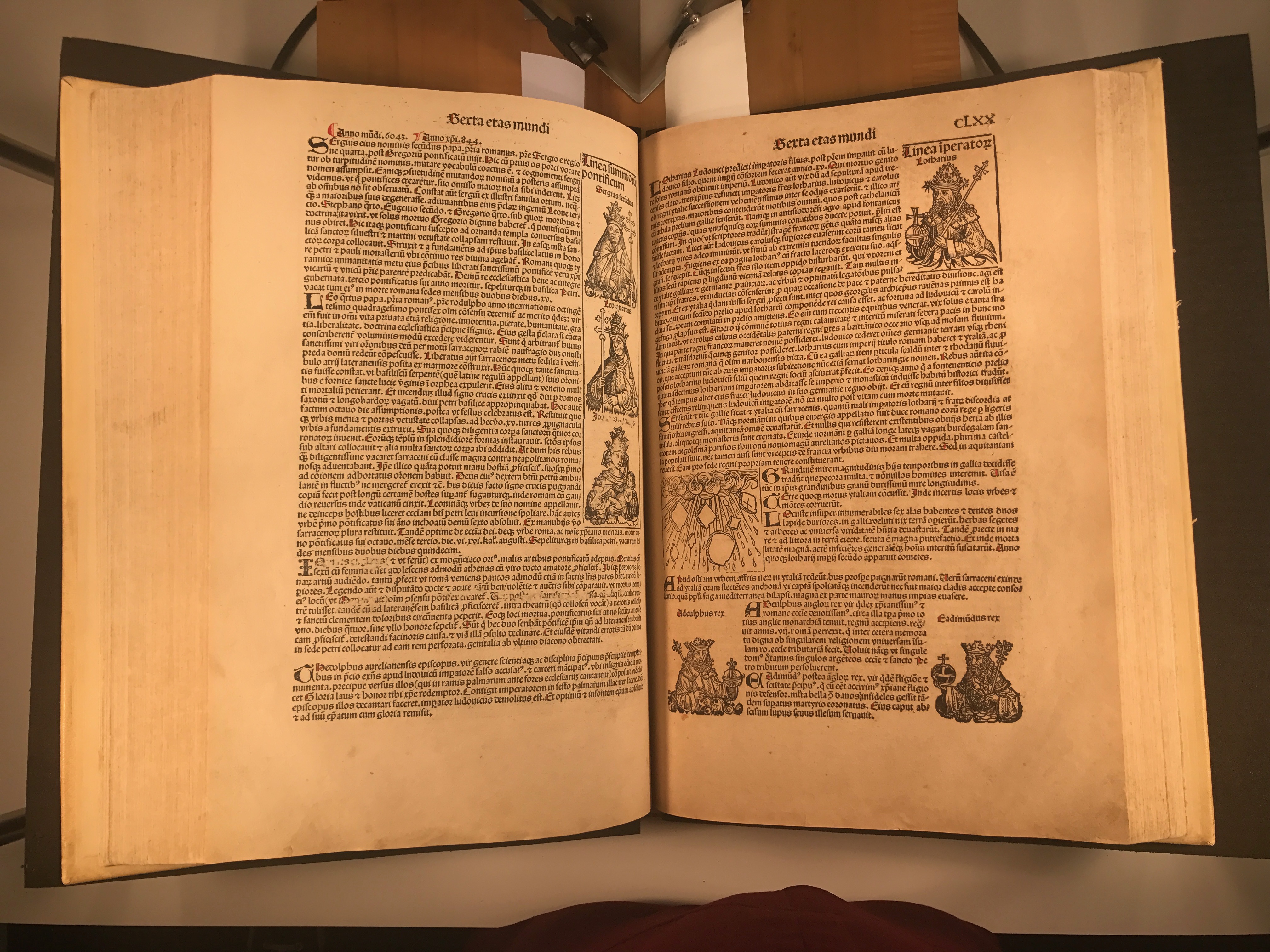

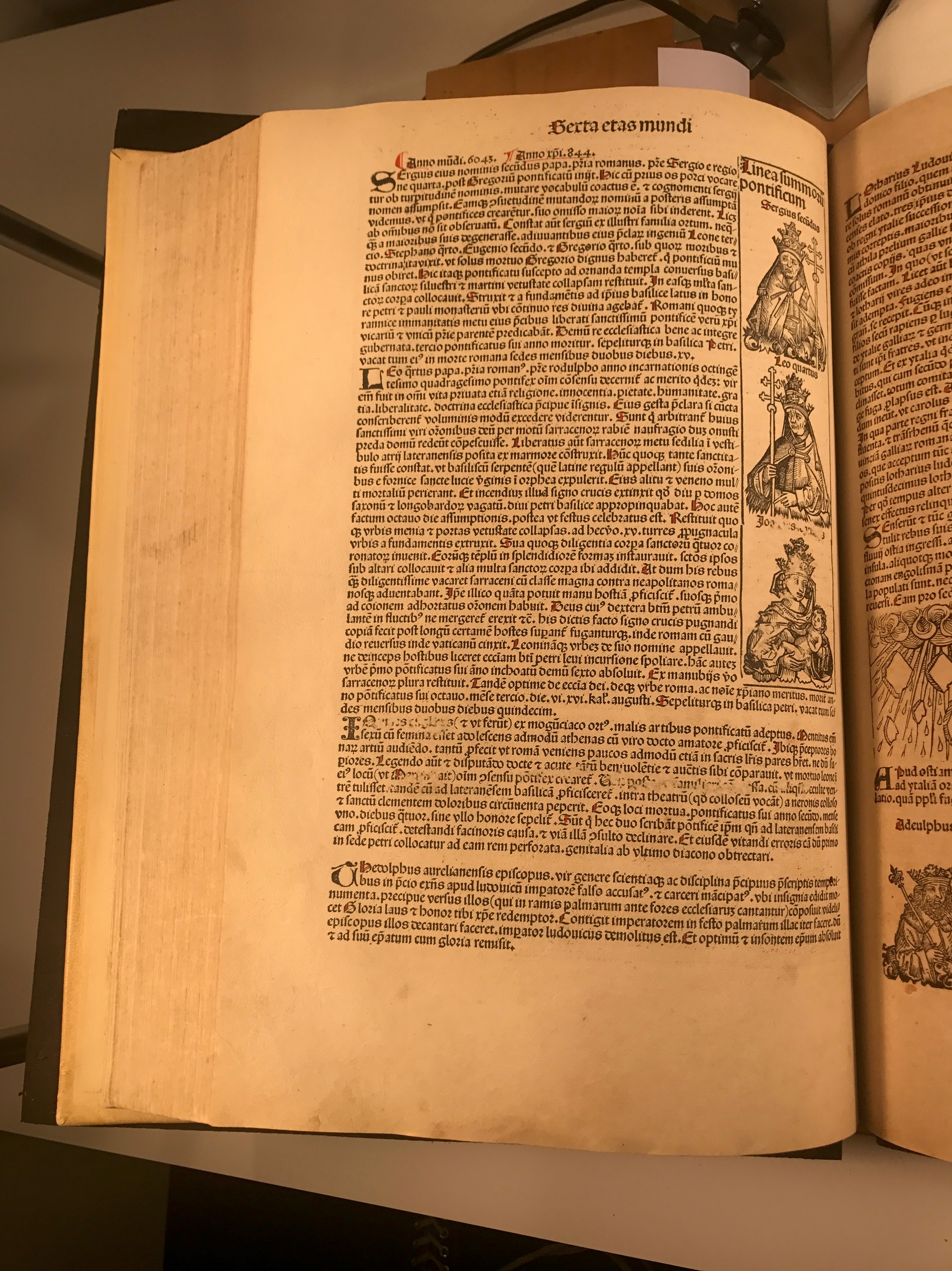

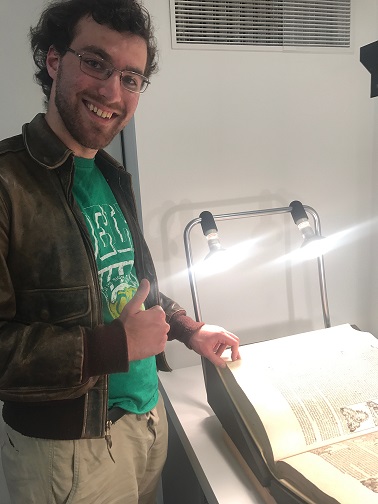

But upon meeting with Bill Monroe, the resident medievalist and early manuscripts librarian at the Hay, Charlie switched gears. Bill and Ann Dodge, the reader services librarian, pulled out the Nuremberg Chronicle, the last major “history of the world” printed in Europe before Columbus reported back his encounter with the New World. A Catholic text, the Chronicle recounts the Creation story and the history of the papacy as part of world history, and Joan makes an appearance.

“When I looked at a vignette of Pope Joan, the woodcut and the text associated with her were both scratched out with a dry quill pen,” Charlie said. Leafing through the rest of the volume, he noticed that Joan’s name and countenance were the only things scratched out.

So Charlie reshaped his research question and began piecing together a microhistory on defacement and myth in the Nuremberg Chronicle. Beginning with the Hay copy, then moving to a few copies at the John carter Brown Library, and finally studying a wide corpus of digitized copies from Boston, Paris, and Germany, he found that the defacing of Joan’s story was “exceedingly common.”

“People would mess with the text differently – they would tear the folio out of the book, sometimes they would stick another piece of paper over Joan’s page, they would scratch it out in ink, or they would write comments in the margins about the heresy of the myth.” The list goes on, and it was clear the that Joan myth touched a nerve with Catholic hands during the Reformation.

Protestants using Pope Joan as anti-Papal polemic is well-established canon, and Charlie read this defacement of the text as the visceral disgust Catholic readers held for this heretical woman pope who posed a threat to the sanctity of the church. Many of the volumes he surveyed were owned by monasteries or prominent counter-Reformation political figures – people invested in historical narratives – and the defacement of the folios manifest that polemic.

Given his use of the Nuremberg Chronicle as the cornerstone of this survey of defacement and the Pope Joan myth, Charlie was awarded the Undergraduate Research Award competition, a $750 prize for the best undergraduate research paper that draws on library resources.