“Working at the Hay has been life-changing for me,” Maya Omori said. “It’s changed the direction of my studies.”

Omori recently received one of the two annual Undergraduate Library Research prizes for her work with the John Hay Library’s archives, Pembroke Center archives, and various university archivists and curators for her senior capstone “Hidden Portraits at Brown.”

Omori, a Cognitive Neuroscience concentrator, became enthralled with the topic of portraiture in History of Art and Architecture Professor Holly Shaffer’s seminar “Portraiture: Pre-histories of the Selfie” in Fall 2018. Returning from winter break in January, she was inspired by the treatment of memory, trauma, history, and space at the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York City and National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., as well as the work of artist Fred Wilson. At the end of the “Selfie” seminar, Omori knew there was more to explore regarding portraiture and representation, specifically at Brown: she asked herself, who gets a portrait, and how does that reveal a community’s values? Drawing together this inspiration, her studies in psychology, and her final paper from Professor Shaffer’s class on unconventional portraits, and with the encouragement of her professors, Omori devised an independent capstone.

“Hidden Portraits,” the fruit of nearly a year’s worth of research, sheds light on “illustrations of our university, sometimes framed but often not, that give us a peek into the history of the institution.”

Building the Project

“Hidden Portraits at Brown” is an interactive teaching and learning experience on the platform Rhode Tour, a web- and mobile-app platform for public-facing, public-access tours of Rhode Island. Every location included on Rhode Tour has to be publicly accessible some number of hours per day, Omori explained.

The public-access element of the tour drove selection of each location, along with establishing a focused thesis or takeaway regarding portraiture and representation. The tour begins in Sayles Hall to introduce the idea of portraiture, but even in Sayles, “I start to challenge what people’s ideas of portraiture is like. Even within the institution of portraiture, if you compare Ruth Simmons versus Tom Tisch’s portraits, you get such a different message,” Omori said.

Each stop on the tour required different elements to bring the history off the screen and into the viewers’ minds. Omori learned audio and video editing to incorporate interviews with archivists, professors, and curators. She also had to learn how to write in a new way to reach her audience.

“The paper I wrote [on portraiture] first semester was an academic paper with tons of peer-reviewed sources, but Rhode Tour is public-facing, it’s not for an academic audience,” Omori said. “With each section of the tour, I tried to pretend I was having a conversation with someone on the street. It’s a completely different method of narrative.”

“The point was to ask more questions than provide answers,” Omori added. Each stop offers a unique and concise entry point into portraiture and representation, whether through analyzing race, class, gender, labor, and ecology, among other topics. Omori wanted the viewers to leave the tour with a toolkit for interrogating the histories of any place they encounter.

The Quiet Green offers a “fascinating juxtaposition” between these various messages and Omori’s own skill in bringing these narratives together. In one corner, the Slavery Memorial marks Brown’s history and perpetuation of the institution of slavery. University Hall, partially built by slave labor, honors George Washington’s one-night stay in the building with a prominent plaque. In these portraits, Omori notes the tensions between recognition of labor, race, and pedestaling historical figures despite their cursory impact on a place.

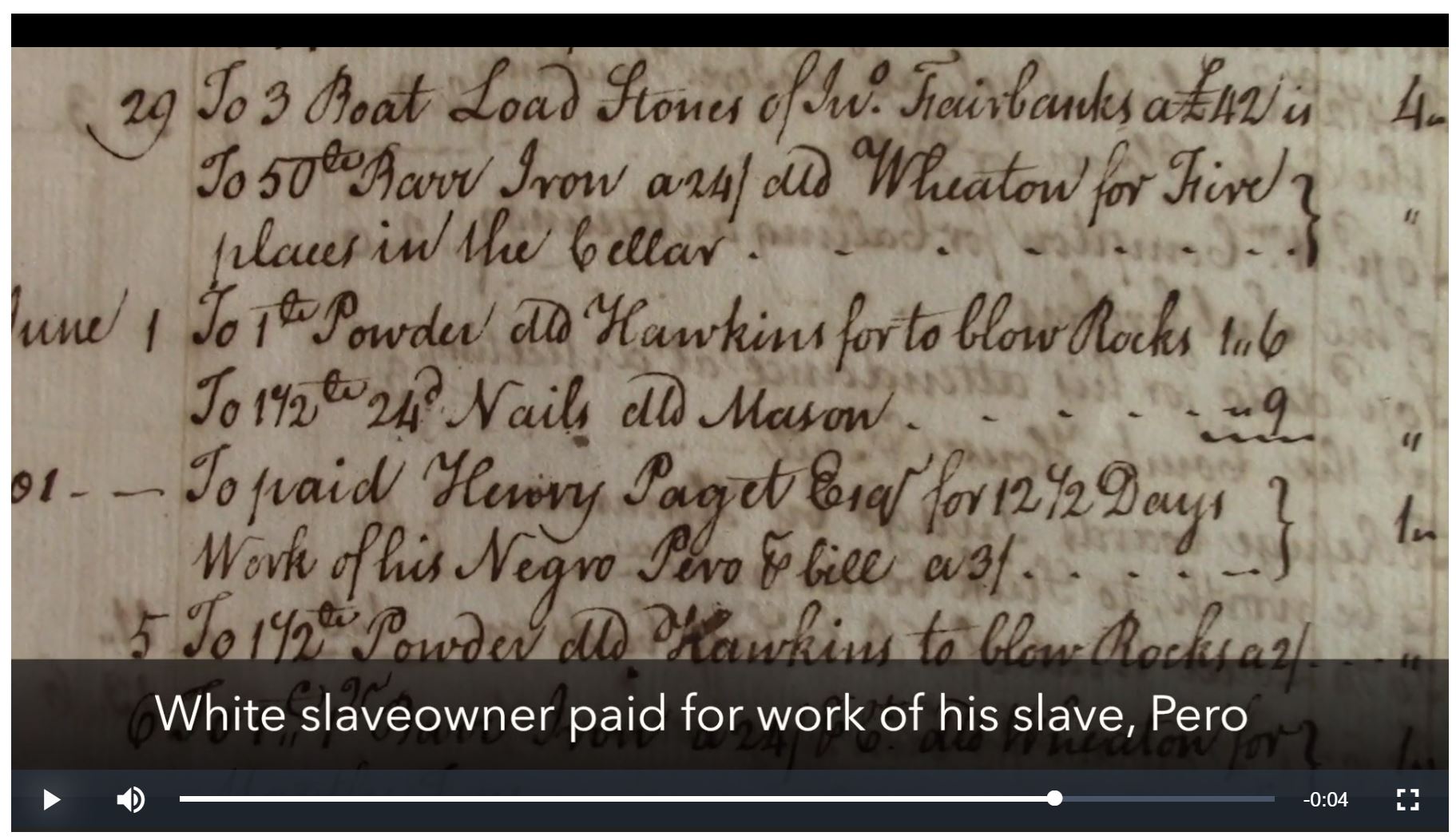

“Washington gets so much more credit on this campus than he deserves, in my opinion. For over 200 years, every winter, we light candles in the University Hall windows to memorialize Washington, despite the fact he was here for one day,” Omori noted. “But four slaves built University Hall.” In the tour, she includes images of the slave ledgers that document their labor on the grounds.

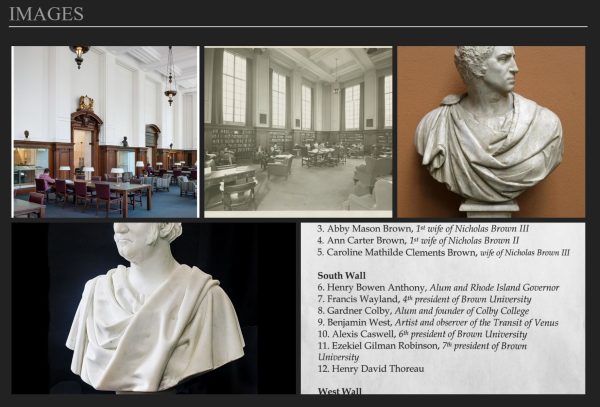

The tour shifts to the Slavery Memorial and then the Van Wickle Gates, where Omori interrogates the “myth as the portrait,” critiquing gender and history at Brown, before moving into the John Hay Library itself, where Omori questions the labels of the white marble busts peering over students in the Reading Room.

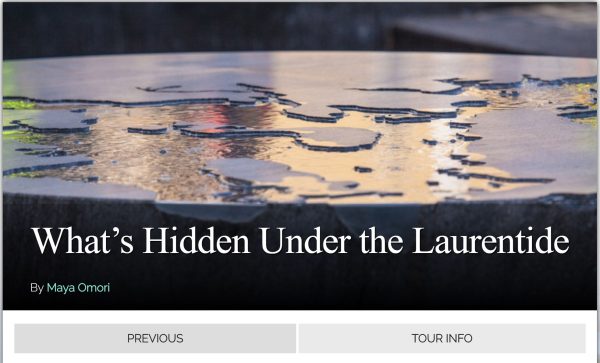

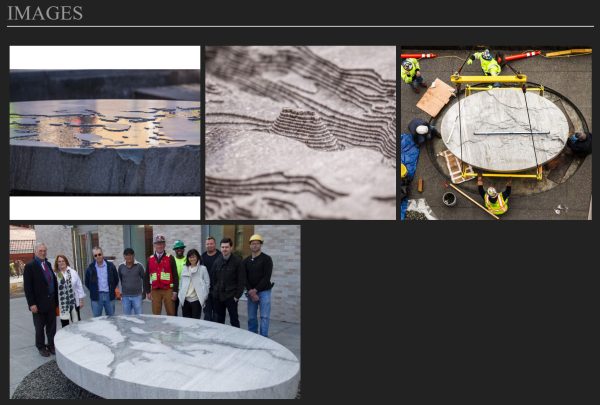

Hidden Portraits moves to north campus, dwelling in Pembroke Hall and discussing Pembroke Women’s College, continuing the conversation of gender, restriction, and conservatism. The tour then concludes at “Under the Laurentide,” a granite sculpture by Maya Lin outside the Brown Environmental Research and Teaching. Omori wanted to conclude with Lin, who is Omori’s namesake, because Lin draws together land, place, and history in a “poetic, profound way.”

Using the Archives

Because each stop offers a different set of questions, Omori found that each location similarly offered a different research experience: she sought out experts on campus and primary documents best suited to each location. Moreover, each stop posed another opportunity to question her own positionality in regards to these topics.

“History is never neutral, so I was constantly thinking about bias in dominant narratives of history. How do I amplify the voices of the less represented while also bringing the largest audience possible into the conversation? There are so many perspectives to each topic, and I knew I couldn’t represent all of them equally.”

This question always returned Omori to the primary sources.

“We often don’t even just take the time to think about the context. That’s why the primary sources were almost like expanding a surface area” on each topic, Omori said.

Viewing and working with primary sources was an integral element of building the Rhode Tour. For the Slavery Memorial and Pembroke Hall stops in particular, Omori worked with archives and primary documents for hours.

“The experience of interacting with primary sources was profound, and … I decided this actual act of interacting with the source must be in the final project.”

As much as possible, Omori sought to bring tangibility to each location: she includes images of primary documents in various stops. The Pembroke Hall stop features film of her flipping through blueprints for Pembroke Hall, and the Willis Reading Room at the John Hay Library includes a panning shot of Omori’s view point of the busts perched on the shelves.

“I fell in love with Public Humanities through this project,” Omori said. “I totally felt empowered through interpretation of objects and space, and I wanted to give that to whoever engages with this project.”

Omori is moving to Cincinnati after graduation and hopes to volunteer at one of the many cultural centers or museums in the city before possibly pursuing further education in public humanities. Omori noted, “I’m excited for my job but at the same time, this project informed what I want to do after.”