Brown University’s Two Copies of “The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare”

In his census of copies of Shakespeare First Folios compiled in 1902, Sidney Lee devised a classification system for condition. The John Hay Library copy is a IIC: imperfect but not thereby “defective” copies, in “moderate” condition, with most of any preliminary or other missing leaves in facsimile or from later folios. The copy in the John Carter Brown Library, on the other hand, is one of a dozen or so classed as IA, perfect copies in good, unrestored condition.

The John Carter Brown Library Copy

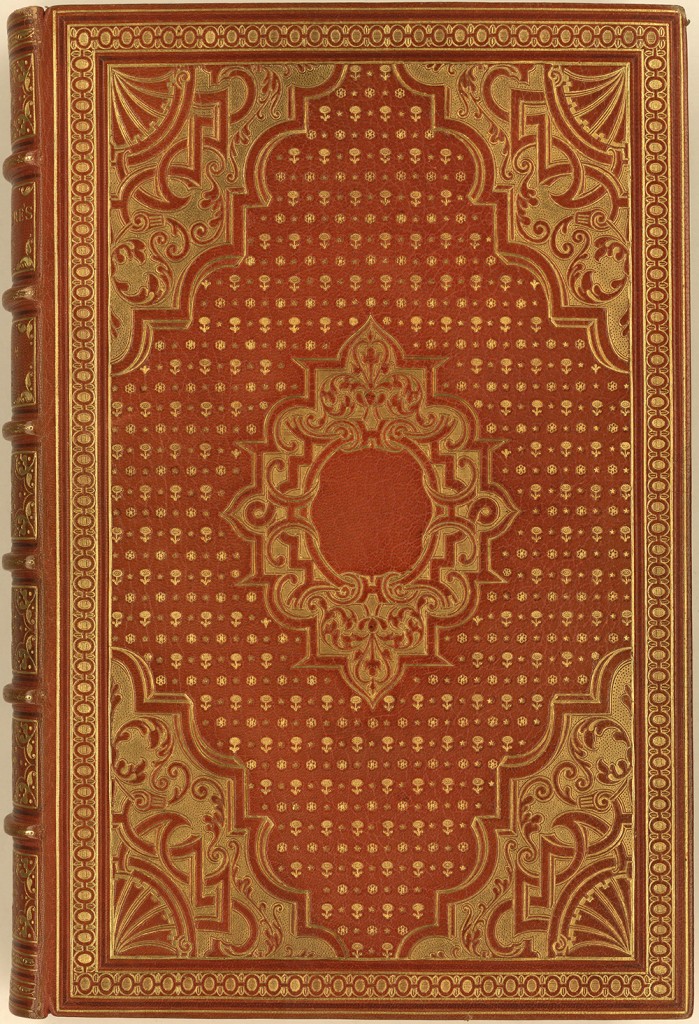

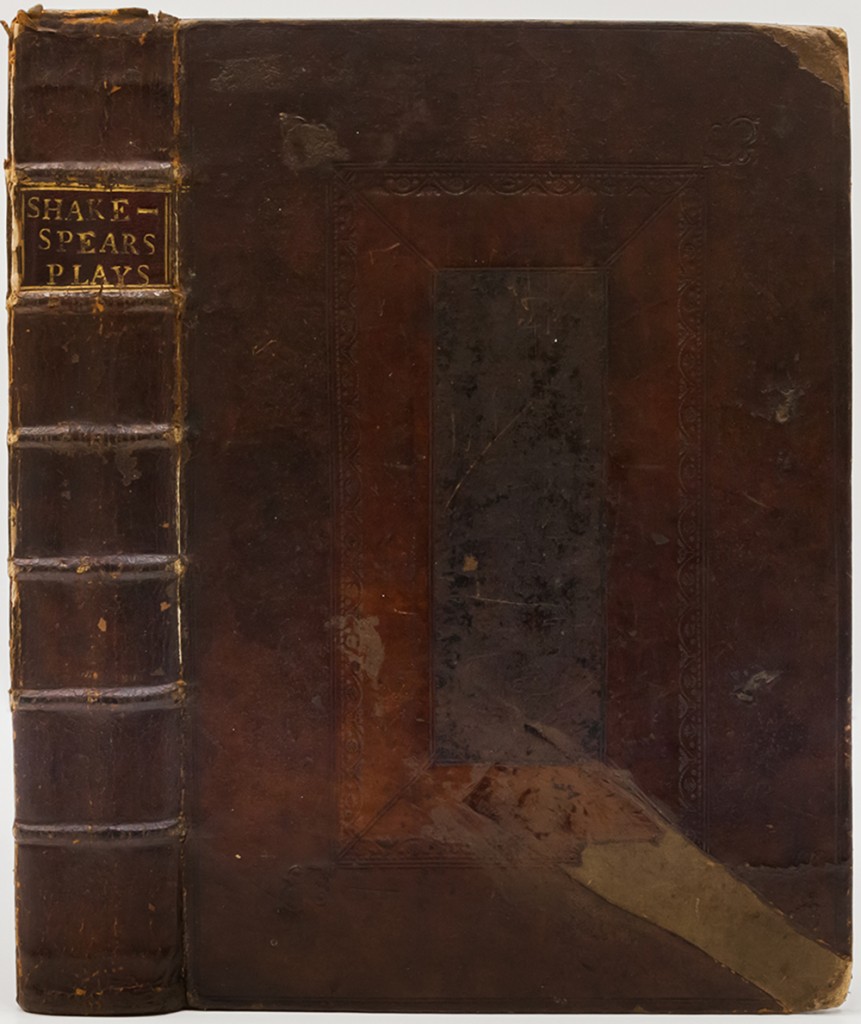

According to the bookseller F. S. Ellis, from whom Mrs. John Carter Brown bought this copy of the First Folio in 1879, we know, or are told at least, that the previous owner, Robert Samuel Turner (1818-1887), had acquired it “about twenty years ago” (about 1860) in a “seventeenth-century binding.” William Younger Fletcher, in his English Book Collectors, published in 1902, described the Turner copy as “one of the finest copies in existence of the first folio,” which Turner “sold privately to an American collector.” When Turner acquired the book the text leaves were almost certainly complete and minimally damaged: Donald Farren, who cataloged all 80 or so of the Folger Shakespeare Library copies in the early 1990’s, noted in personal correspondence that the JCB copy is “virtually unrepaired.” The upshot is that this may actually have been a much better copy before Turner had it re-bound, judged by present-day standards by which we tend to prefer a physical book that is more like an undisturbed archeological site than a skilled reconstruction from original materials.

It is, in its outward aspect, an utterly nineteenth-century book in an antique style. Every trace of its pre-1860 history, if traces there were, has been erased by Turner’s binder, Francis Bedford, whose elaborately blocked and tooled leather covers enclose a printed text that has been disassembled, washed and pressed, and put back together better than it looked alive. It has, in effect, been embalmed and well made up, more for reverential viewing than for reading. All that has been added, on the fine vellum front free endleaf, is the signature “Sophia Augusta Brown.”

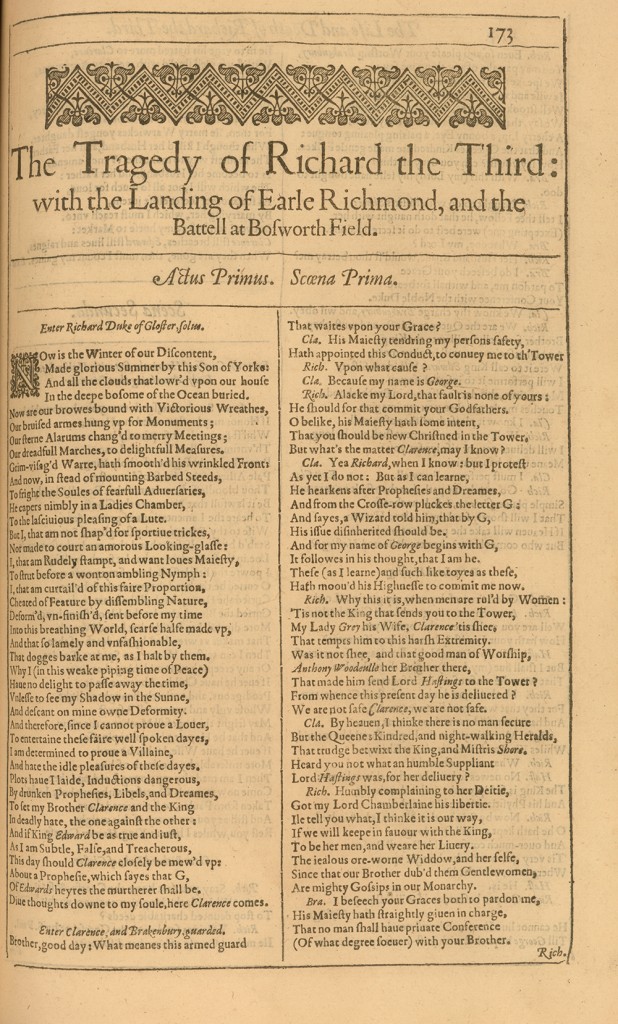

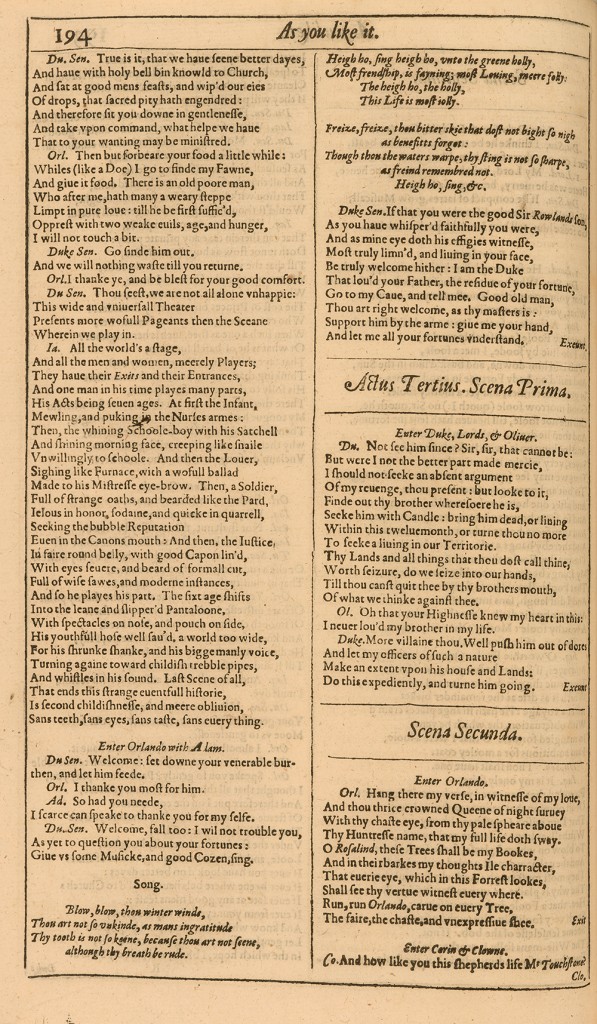

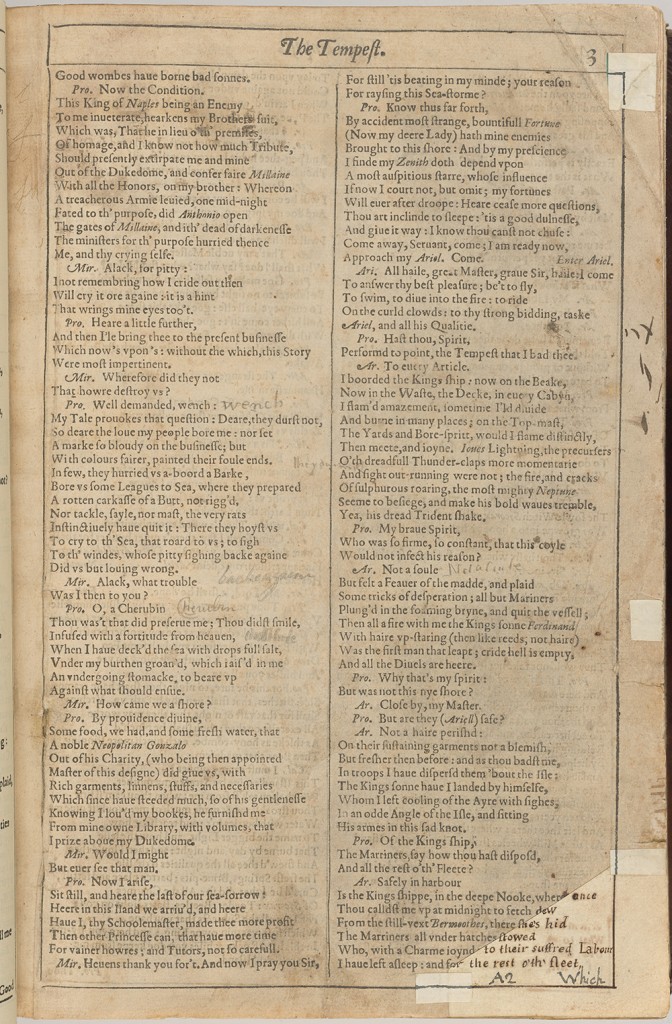

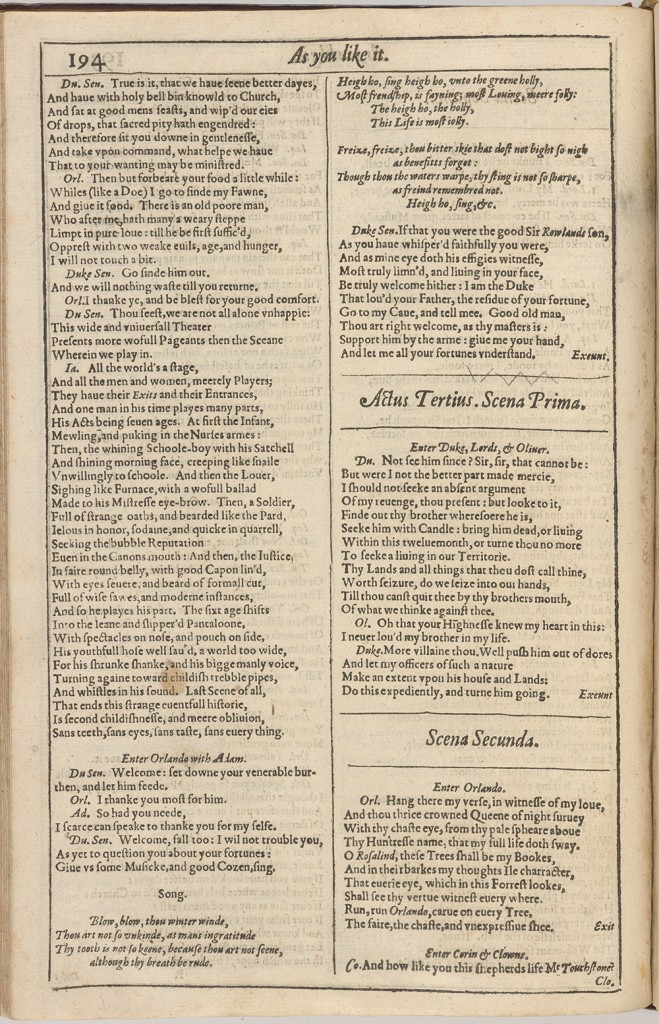

“Embalmed” is an exaggeration of course. One of the very rare complete and original copies, this book, which cannot have been read too hard at any time, whether out of reverence or benign neglect, remains an invaluable witness among its fellow witnesses to many works which would otherwise have been lost in all but their titles, gone the way of Love’s Labours Won. Read aloud from it, and it breathes again — but don’t breathe on it!

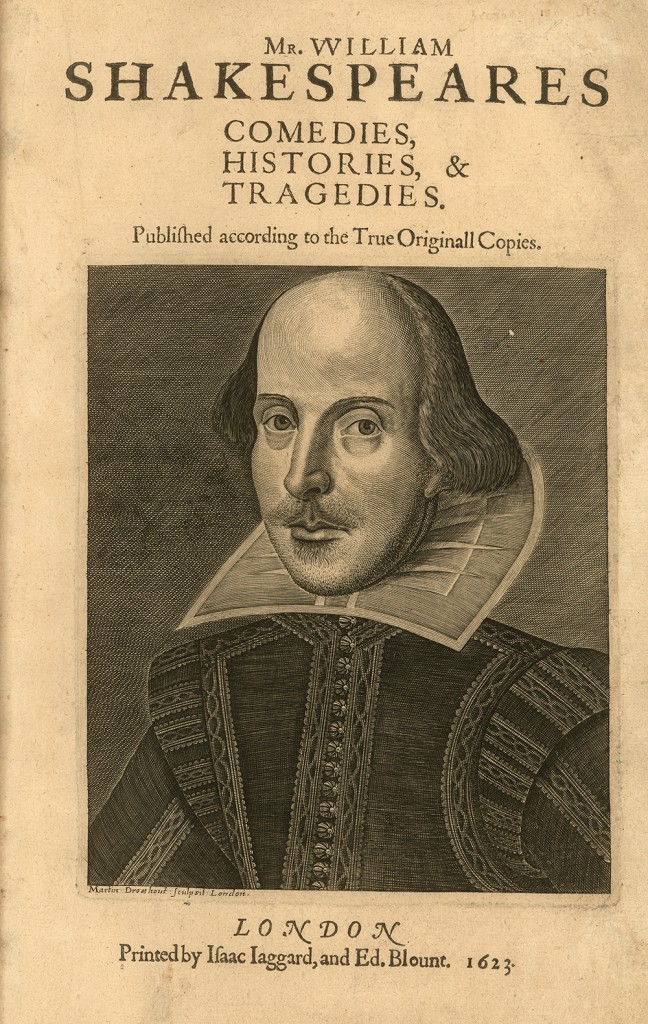

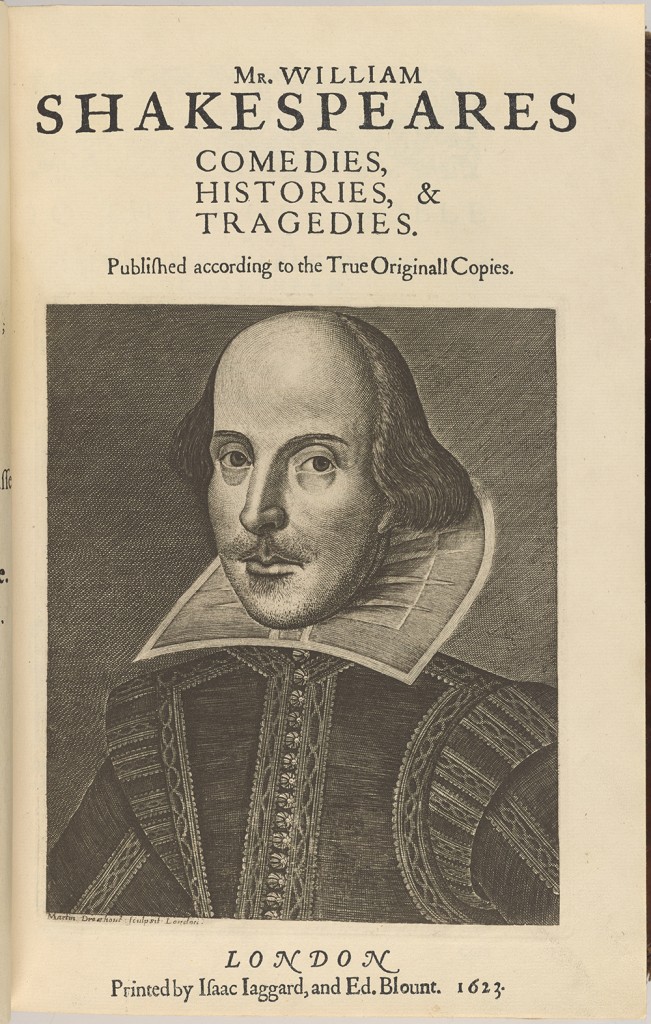

A couple of details: This copy has the engraved portrait in its earliest state (no shadow on Shakespeare’s collar); also Troilus and Cressida is placed incorrectly after Timon of Athens and before Julius Caesar. The latter, “an odd quirk of this volume,” and many, many other details are noted in Eric Rasmussen and Anthony James West, The Shakespeare First Folios: A Descriptive Catalogue (2012), in which the John Carter Brown and John Hay Library copies are nos. 183 and 184. Painstaking description is given under such categories as condition, manuscript annotations, repairs and damage affecting text, repairs and damage not affecting text (which include such things as comparative stiffness and variant margins of individual leaves), along with complete registers of press variants and of the occurrence of every one of the various watermarks. The authors’ purpose is to provide the equivalent of a set of fingerprints for every copy, so that even a copy that has been stolen and had its more obvious identifying marks removed can be positively identified by anyone with basic knowledge of the physical composition of printed books. Here the modern form of reverence — or at least of high valuation — is observed, not in the effacement of quirks and blemishes but in the minutest possible account of them.

The John Hay Library Copy

The John Hay Library copy wears its past much more obviously. Its known provenance (history of ownership) is accordingly more complicated than that of the JCB copy. It also displays a fair number of surgical scars — torn corners and edges rather amateurishly repaired at various times, partly using what look like adhesive stickers, with the bits of missing text restored in pen-facsimile (hand written in imitation of type). Extra leaves inserted between the front cover and the text include a virtual scrapbook of owners’ marks, notes, and a few souvenirs.

After Sir Fulwar and possibly the Rev. Mr. Johnson, there is a gap of a century, more or less, and it turns out that the book has moved to Shakespeare’s birthplace, Stratford-upon-Avon, and become the property of the Rev. John Day Collis (1816-1879), Vicar of Trinity Church, under the floor of which are Shakespeare’s bones. Three bookplates were added on other leaves by a later owner, Captain William Jaggard (1868-1947), possibly but not provably a descendant of William Jaggard, the printer of the First Folio: the woodcut bookplate “Ex libris Gulielmus Jaggard” includes the printer’s device. The later Jaggard was proprietor of the Shakespeare Press in Stratford, “where exists the largest stock of out-of-print Shakespeareana in the world,” as he noted at the end of his massive and still cited Shakespeare Bibliography (1911). He, or Collis, may have been the one who pasted in three souvenir engravings of the Shakespeare birthplace, birth room, and Shakespeare monument in Trinity Church. Another souvenir, probably not an indication of ownership, is the manuscript of a sonnet, “On the First Folio,” signed HS, who is identified in a note as Howard Staunton (1810-1874), best known as a chessmaster (and designer of the now standard chess pieces), who also produced in 1866 the first photographic facsimile of the First Folio. From a bookseller’s notes on the inside front cover, datable to 1928, we know that the adhesive mounts on the third preliminary leaf once attached a rather inaccurate re-engraving of the Droeshout title-page portrait, made for an edition of Shakespeare’s plays published by John Stockdale in 1790.

The next recorded owner was Alfred MacArthur, of Chicago (brother of John D., founder of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation), who purchased the copy from the Chicago booksellers Hamill & Barker in 1958; their description stated that “the father of the present [unidentified] owner purchased the volume in 1928 from Mr. E. Thompson who was acting on behalf of Captain William Jaggard.” On Alfred MacArthur’s death in 1967 the copy went to his daughter, Georgiana MacArthur Hansen, who, with her husband William V. A. Hansen, formally presented it to Brown University on Shakespeare’s 407th birthday, 23 April 1971, in memory of her father. (The Hay’s collection files make the connection: Mrs. Hansen’s first husband, killed in naval action in 1945, was Henry Brayton Gardner, Jr., whose father graduated from Brown in 1884 and went on to become head of Brown’s Department of Economics; her son Robert MacArthur Gardner was in the Brown Class of 1959.)

The first ten and last five original leaves of the book itself, as well a single leaf in the text, are lacking, supplied in facsimile, and there are signs that a few leaves at various points in between may be substitutes from other copies (a frequent practice beginning in the 18th century, accelerating greatly in the 19th). It is likely that the outermost leaves were already gone when the book was bound in the early 18th century. The present facsimile leaves were probably added by Jaggard: they come from a line-block facsimile (with the portrait in collotype) published in 1910 by Methuen & Co., which, like other facsimiles before it, including that of Howard Staunton, would have been a good source of leaves to fill out incomplete copies.

The known history of the Hay copy spans the years during which what was simply the first collected edition, folio, of Shakespeare’s plays (1623) became The First Folio. When its quite ordinary binding was executed this was simply a secondhand book, long since superseded by the Second, Third and Fourth Folios of 1632, 1663 and 1685. Copies could still be bought for comparatively little money, and might be read to death, or perhaps cut up and used for amateur theatrical productions. Its rise in value and venerability began soon after that; at a later time someone noted on the front pastedown, “This is the precious First Folio of 1623.” Nowadays we keep it close, handle it very carefully, and read from it with a sense of wonder — and gratitude to those who were its custodians before us.

Credits:

Notes by Richard Noble, Rare Materials Cataloger in the Brown University Library, January 2016.