Figs. 1a & 1b (series):

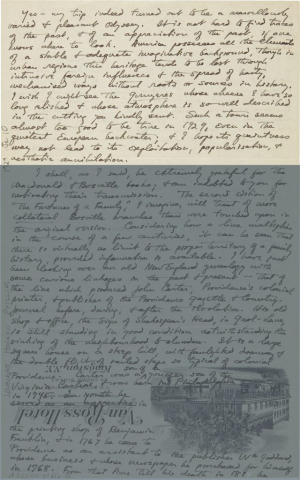

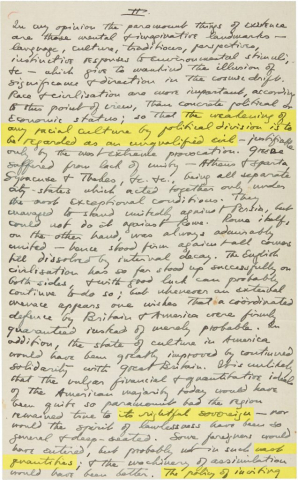

Writing to Donald Wandrei in 1927 (fig. 1a), Lovecraft admits to “believing the cosmos to be a purposeless and meaningless affair [. . .] a thing without beginning, permanent direction, or ending.” Lovecraft sees “no such qualities as Good or Evil, beauty or ugliness, in the ultimate structure of the universe.” This serves as the fulcrum for his staunch traditionalism: Given that this is the “ultimate structure of the universe,” Lovecraft continues, “I insist on the artificial & traditional values of each particular cultural stream proximate values which grew out [. . .] of the race in question.” For Lovecraft, the practice of “extreme conservatism” is “the only means of averting ennui, despair, & confusion of a guideless & standardless struggle with unveiled chaos.” Discussing the topic with Elizabeth Toldridge in 1929 (fig. 1bi–iii), he concludes that the “potent emotional legacy” that he calls “tradition” is “bequeathed to us by the massed experience of our ancestors, individual or national, biological or cultural.”

The key to Lovecraft’s brand of traditionalism is his concept of “cultural stream”: a strange amalgamation of race realism (i.e., the belief in discrete “human races”) and cultural traditions, which becomes the sole basis for human meaning. Lovecraft conceives cultural streams as being incompatible with each other: “what gives one person or race [. . .] relative painlessness & contentment often disagrees sharply on the psychological side from what gives these same bases to another person or race” (fig. 1biii). Thus, for these “cultural streams” to provide meaning, they need to remain essentially unchanged and entirely separate. The “weakening of any racial culture by political division,” he writes in another letter to Toldridge (fig. 1ci), “is to be regarded as an unqualified evil.”

Figs. 1c, 1e, & 1f (series):

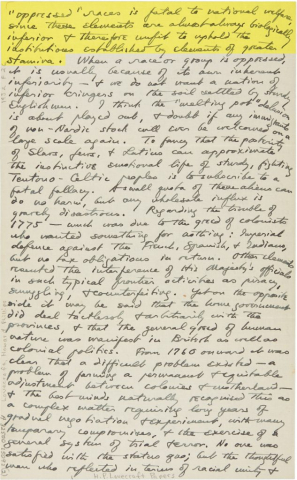

Let us consider how Lovecraft’s “extreme conservatism” based on this concept of “cultural streams” can lead to a xenophobic and racist political program. In the same letter to Elizabeth Toldridge (figs. 1ci–ii), Lovecraft laments that the independence of the United States from “its rightful sovereign” permitted “vast quantities” of foreigners to immigrate and that “the policy of inciting ‘oppressed’ races is fatal to the national welfare since these elements are almost always biologically inferior & therefore unfit to uphold the institutions established by elements of greater stamina.”

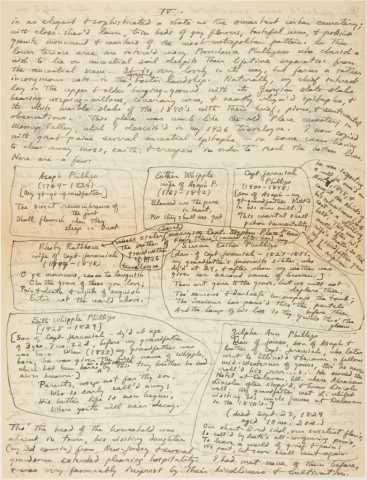

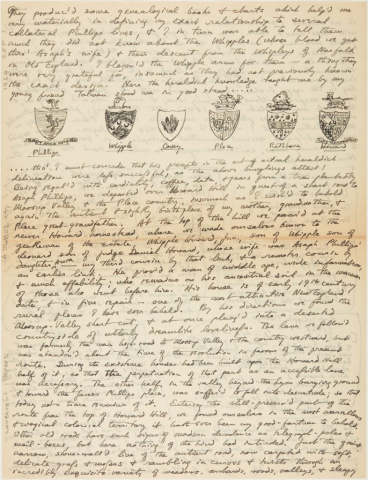

In Lovecraft’s personal life, this traditionalism took shape in his keen interest in his family’s genealogy. In a 1929 letter to Maurice W. Moe (figs. 1ei–iii), Lovecraft describes at length one of his “ancestral pilgrimages,” trips he took to the New England countryside to learn more about his ancestry. After sharing with Moe sketches of tombstones and family shields, Lovecraft writes about his perspective on life there:

Here, indeed, was a small & glorious world of the past completely sever’d from the sullying tides of time; a world exactly the same as before the revolution, with absolutely nothing changed in the way of visual details currents of folk-feeling, identity of families, or social & economic order.

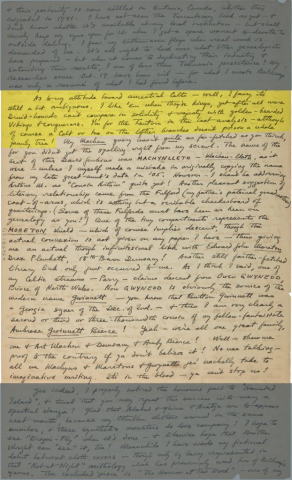

As will be demonstrated in section 4, this genealogical obsession combined with an intense attachment to “cultural streams” can be the source of horror. In a letter to Wilfred B. Talman in 1927 (fig. 1f), Lovecraft discusses having Celtic ancestry:

As for my attitude towards ancestral Celts — well, I fancy it’s still a bit ambiguous. I like ’em when they’re kings, yet after all mere Druid-hounds can’t compare in solidity & majesty with golden-bearded Vikings and conquerors. I’m for the Teuton in the last analysis — although of course a Celt or two on the loftier branches doesn’t poison a whole family tree!