Figs. 2a & 2b (series):

For a better understanding of Lovecraft’s traditionalism based on the idea of ancient, discrete and unchanging “cultural streams,” it is worthwhile to further look at specific instances of his race thinking, with particular emphasis on his anti-Black racism, anti-Semitism and his views on Nazism and Adolf Hitler.

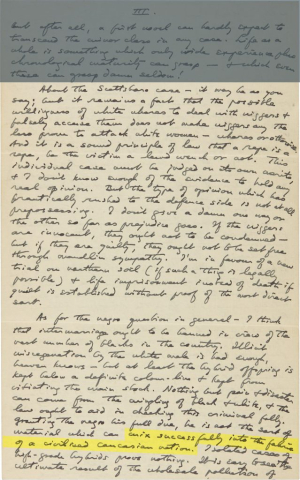

As suggested in his previously highlighted letters, Lovecraft saw the expansion of American urban centers and life in the early 20th century as almost synonymous with civilizational decay. Consider the description of his native Providence in a 1930 letter to Elizabeth Toldridge (fig. 2a):

Our Broadway was once a splendid residential street a mile long & lined with mansions but is now sunk to a slum & is rapidly being engulfed by the vast Federal Hill Italian Colony. Two or three of the old ancient families, however, still cling to their old homes — odd cases amidst a desert of Sicilian squalor and noisomeness!

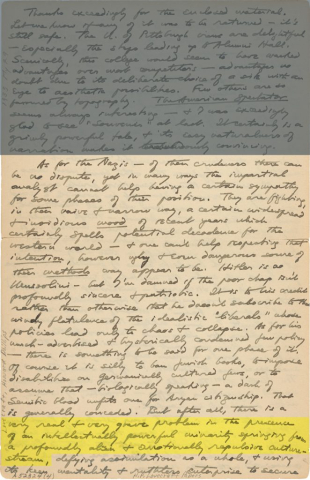

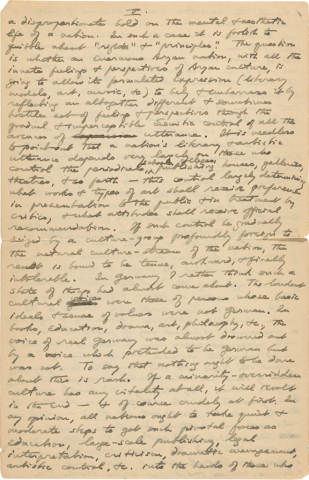

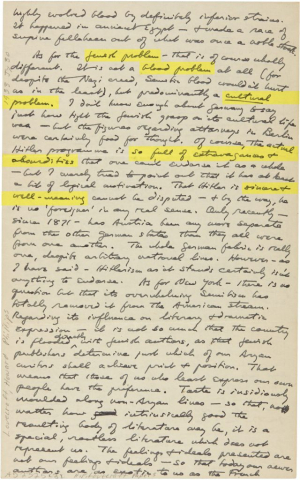

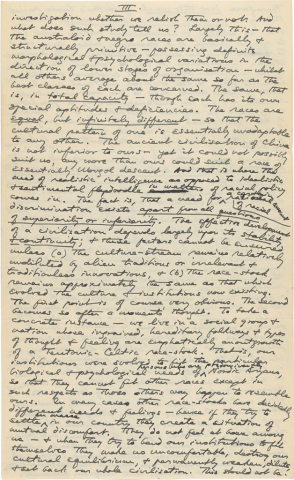

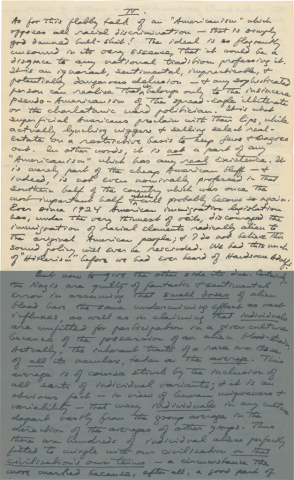

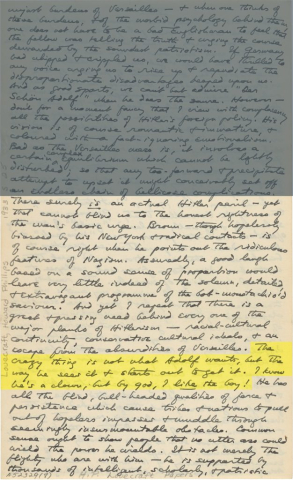

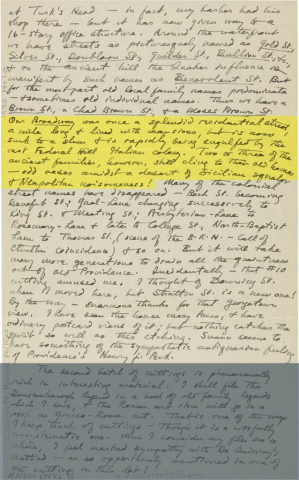

Another instructive example is a 1931 letter to Vernon J. Shea (fig. 2b), with whom Lovecraft frequently discussed his race thinking. In it, Lovecraft discusses the different regional accents in the United States at length and uses these to distinguish what parts of the country are closest to England. Describing the accent of Charleston, South Carolina, one of his favorite places, Lovecraft muses that given the particular set of conditions there, “their speech was too fixed by frequent social use to suffer any modification from the n*gger1 talk around them.” Thus, the Charleston accent is “almost identical with that of the greater part of New England,” the other place in the United States Lovecraft thinks is closest to England.

Figs. 2d, 2e, & 2f (series):

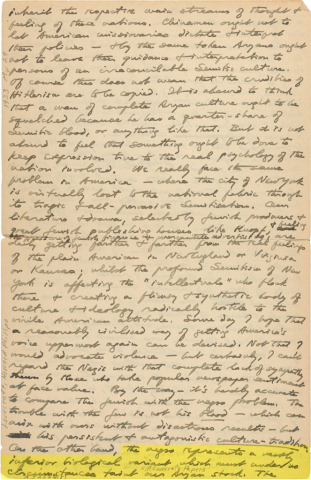

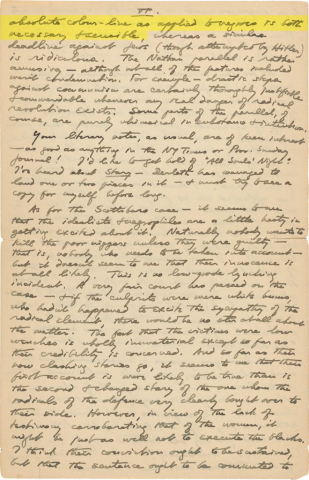

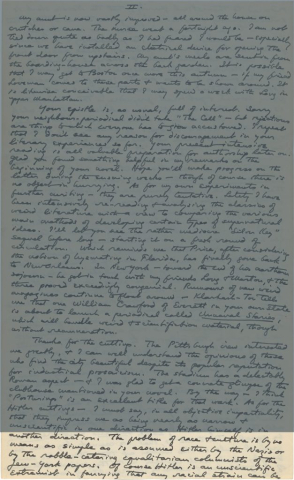

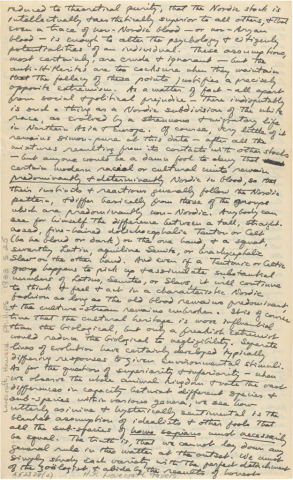

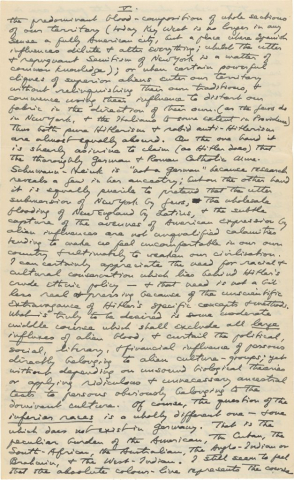

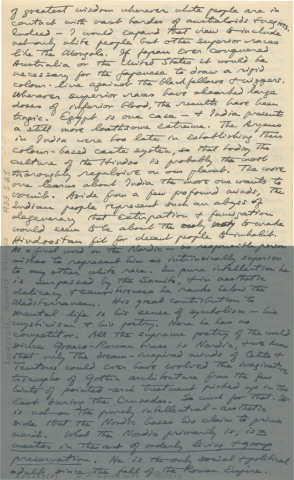

Perhaps the most jarring instances of Lovecraft’s race thinking are exemplified in a multi-letter exchange with Vernon J. Shea between May and September of 1933 (fig. 2d–f). In these letters, Lovecraft discusses his views on Nazism and further clarifies the content of his anti-Black racism and anti-Semitism. Lovecraft’s main disagreement with Nazism is its view of “the Jewish problem” as a “blood problem” instead of a “cultural problem” (fig. 2eii). In other words, Lovecraft thinks Jewish people can be “assimilated” to the “Aryan” “cultural stream,” but that the “problem” is “in the presence of an intellectually powerful [Jewish] minority springing from a profoundly alien & emotionally repulsive culture-stream” (fig. 2di). Here, Lovecraft is clearly echoing anti-Semitic tropes. Thus, although he views Hitler’s political program as being “so full of extraneous absurdities,” he thinks of Hitler as “sincere and well-meaning” (fig. 2eii). Lovecraft would later proclaim that “the crazy thing is not what Adolf wants, but the way he sees it & starts out to get it. I know he’s a clown, but by god, I like the boy!” (fig. 2fvii).

Lovecraft’s anti-Semitism is abundantly clear. However, the most hateful aspect of his race thinking is his anti-Black racism. Contrary to the “Jewish problem,” Lovecraft thinks that “the negro represents a vastly inferior biological variant which must under no circumstances taint our Aryan stock. The absolute colour-line as applied to negroes is both necessary and sensible” (fig. 2diii-iv). Indeed, for Lovecraft, Black people cannot “mix successfully into the fabric of a civilized caucasian nation” (fig. 2ei).

1 A note from the curator: I understand and appreciate that given the racist history of the “N-word” it now is “a word used on black people’s terms” (Ogbar 2008, 68) and thus is not mine to use.

![Fig. 2bi. Letter from H. P. Lovecraft to Vernon J. Shea, dated Friday, envelope postmarked Oct [?] 1931. Brown University Library, Special Collections.<br /> <a target="_blank" href="https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:935972/">VIEW IN COLLECTION (BROWN DIGITAL REPOSITORY)</a> Fig. 2bi. Letter from H. P. Lovecraft to Vernon J. Shea, dated Friday, envelope postmarked Oct [?] 1931. Brown University Library, Special Collections.](https://library.brown.edu/create/lovecraftracialimaginaries/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2020/11/2bi_bdr935972-806x1024-715x480.jpg)

![Fig. 2bii. Letter from H. P. Lovecraft to Vernon J. Shea, dated Friday, envelope postmarked Oct [?] 1931. Brown University Library, Special Collections.<br /> <a target="_blank" href="https://repository.library.brown.edu/studio/item/bdr:935973/">VIEW IN COLLECTION (BROWN DIGITAL REPOSITORY)</a> Fig. 2bii. Letter from H. P. Lovecraft to Vernon J. Shea, dated Friday, envelope postmarked Oct [?] 1931. Brown University Library, Special Collections.](https://library.brown.edu/create/lovecraftracialimaginaries/wp-content/uploads/sites/80/2020/12/EG_2bii_bdr935973-highlights-806x1024-715x480.jpg)