Fig. 3a & fig. 2diii (series):

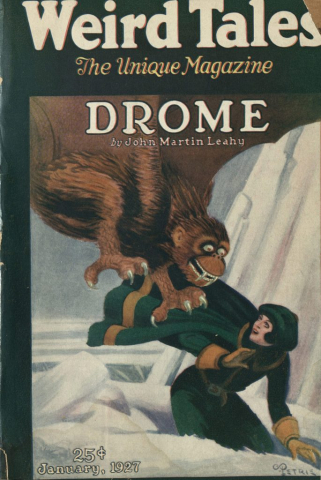

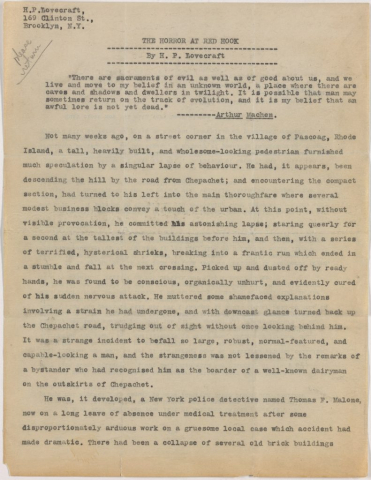

Sections 1 and 2 identified some of the key features of Lovecraft’s race thinking and how these featured in his personal correspondence; we turn to how these were a well of inspiration for his literary input. At times, the link between Lovecraft’s race thinking and his fiction is quite explicit. One of the best examples is his short story “The Horror at Red Hook.” Written while Lovecraft was living in New York City in 1925 and published in 1927 (fig. 3a), “Red Hook” tells the story of NYPD detective Thomas Malone and his uncovering of “a clan of devil-worshippers” in the neighborhood of Red Hook in Brooklyn.

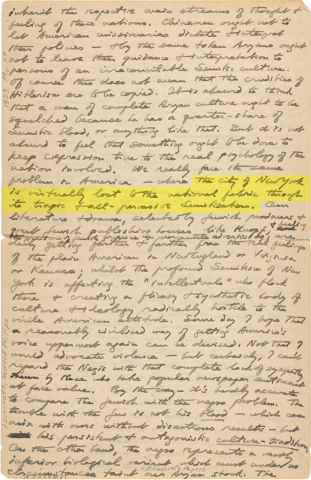

As some of the letters exhibited in the previous sections show, Lovecraft had a particular disdain for New York. Writing to Vernon J. Shea in 1933 (fig. 2diii), Lovecraft states that “the city of New York is virtually lost to the national fabric through its tragic & all-pervasive Semitisation.” Indeed, it seems that for Lovecraft, New York, as one of the most prominent urban centers in the country and symbol of the “melting pot” ideology, represents all of his horrors of racial, ethnic and cultural exchange.

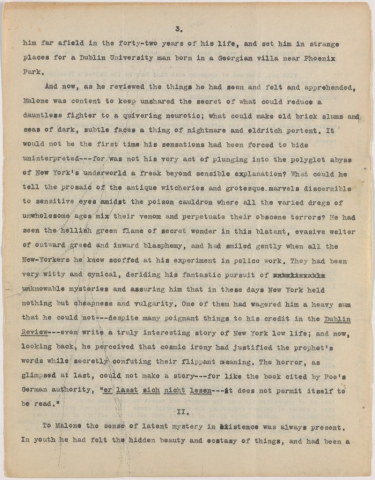

At the beginning of the story, the narrator explains that Malone had to leave New York for rural New England because of “a horror beyond all human conception — a horror of houses and blocks and cities leprous and cancerous with evil dragged from elder worlds” (fig. 3bii). Consider the first description of the inhabitants of Red Hook: “The population is a hopeless tangle and enigma; Syrian, Spanish, Italian, and negro elements impinging upon one another, and fragments of Scandinavian and American belts lying not far distant. It is a babel of sound and filth” (fig. 3biv).

Fig. 3b (series):

This, however, was not always the case. Reminiscent of Lovecraft’s description of Providence highlighted earlier, in Red Hook, “long ago a brighter picture dwelt, with clear-eyed mariners on the lower streets and homes of taste and substance where the larger houses line the hill” (fig. 3biv–v). It is evident in the story that diversity is both the cause and the sign of decay. Additionally, it becomes a broader and more existential threat once Malone discovers that the inhabitants of Red Hook belong to the “Yezidi clan of devil-worshippers” and plan to make a satanic ritual. In the end, the cult is uncovered and its plans thwarted. Yet, reflecting Lovecraft’s xenophobia, Red Hook “is always the same.” Thus, “the evil spirit of darkness and squalor broods on amongst the mongrels in the old brick houses, and prowling bands still parade on unknown errands past windows where lights and twisted faces unaccountably appear and disappear” (fig. 3bvii–viii).