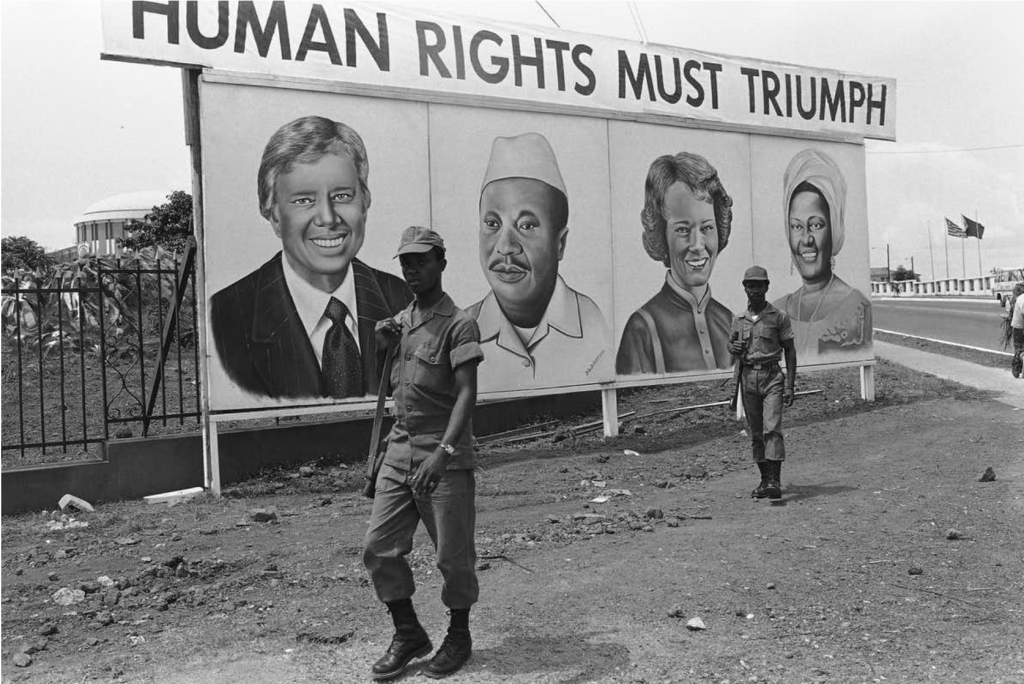

Washington was quick to recognize the military coup in 1964. During the initial years of the new regime, public opinion in the U.S. was favorable to the generals and saw military rule as a genuine salvation of Brazil from a communist threat. While this was clearly far from the truth, news coverage in the United States was biased and counted on one-sided accounts of events. With time, however, as the regime eroded democratic rights and as reports of torture started increased, a small movement of grassroots activists started to organize in the United States. Formed by a decentralized coalition of Brazilian émigrés, Latin American studies scholars, sympathizers, and religious leaders, these groups started publishing periodicals to consolidate information on the regime’s abuses. At that time, some Brazilian artists, thinkers, and prominent figures were living in the United States either in exile or in search of professional opportunities no longer available in Brazil due to the military’s control over cultural expressions. Eventually, these groups managed to get important mainstream newspapers, such as the Washington Post and the New York Times, to pick up stories about human rights violations in Brazil. They also successfully lobbied Congress to take a tougher stance on U.S. aid being provided to countries with negative human rights records. While the issue of Brazil never elicited widespread outrage, it laid the groundwork for a broader movement in defense of human rights in Latin America, as Chile and Argentina joined Brazil as authoritarian nations with records of torture. Human rights was still a new expression in the political lexicon, used by Jimmy Carter in his run for office. Although he promised to make defense of human rights a cornerstone of U.S. Foreign Policy, in practice the Department of State took on a pragmatist, case-by-case approach in determining American actions. That meant that his policies were at times contradicting, cutting slack for allies such as Brazil and Iran while pressing on other cases such as Nicaragua.

Readings:

James N. Green, “Clerics, Exiles, and Academic: Opposition to the Brazilian Military Dictatorship in the United States, 1969-74.” | English

David P. Forsythe, “American Foreign Policy and Human Rights: Rhetoric and Reality.” | English

Profile in the New Yorker on Helio Oiticica – Paints a picture of self-imposed exile life for an artist

Documents:

Read selections from the “Brazilian Information Bulletin”:

1st Edition: “What is Happening in Brazil”

4th Edition: “Brazil’s “Economic Miracle””

6th Edition: “Nixon Christens Brazil a Sub-imperial Power”

10th Edition: “Catholic Church Turns Back on Generals”