Crafting a Cosmos

To explain that infernal theater, it was necessary to have a geographer and architect of the most sublime judgment, as, in the end, our Dante has proved. If he who so sublimely developed the wonderful construction of the heavens, and so exquisitely designed the place of the earth, was reputed worthy the name of divine, then for the reasons already given, hasn’t our Poet earned that name yet again?

—Galileo, 1588

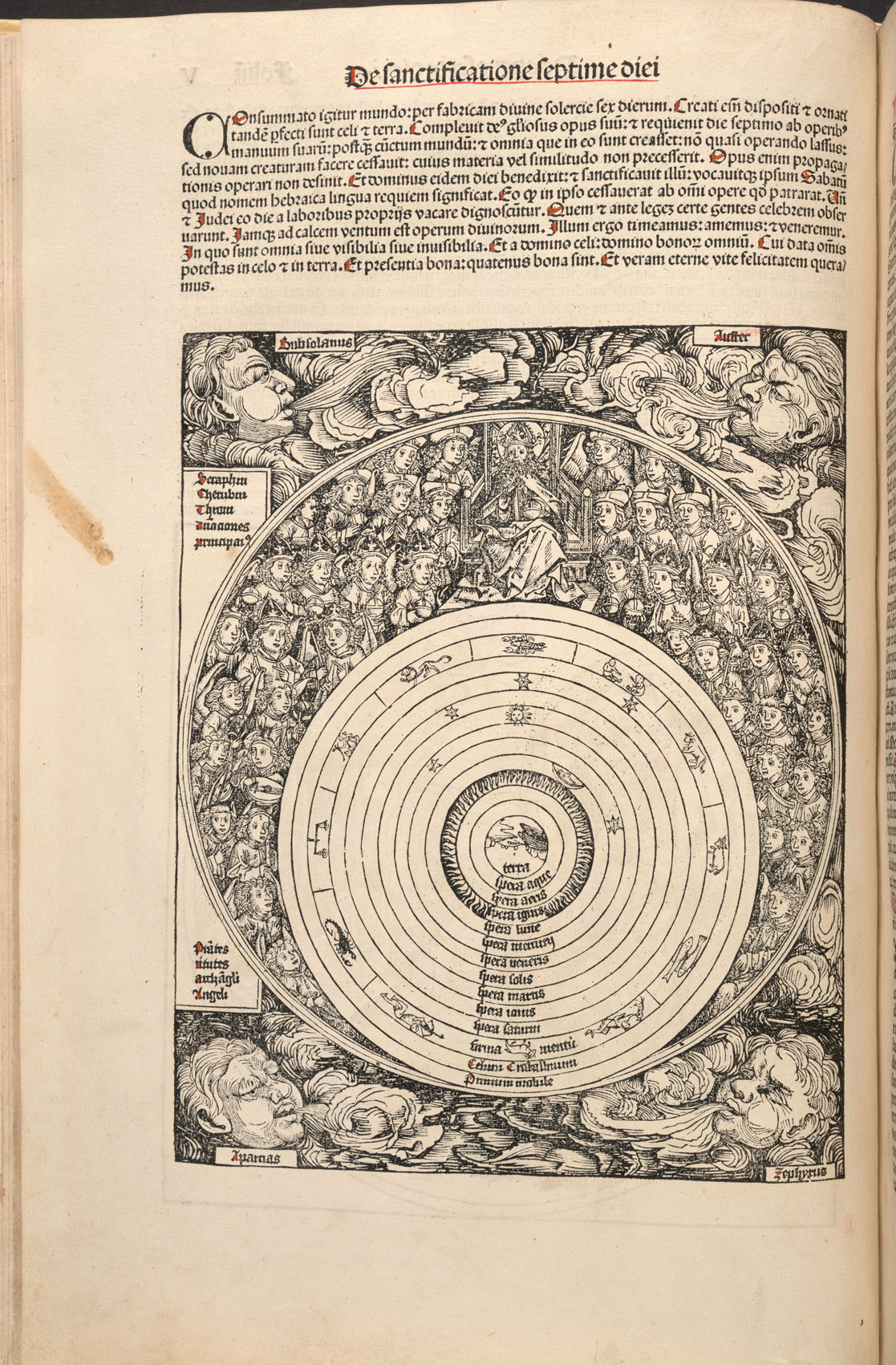

Hartmann Schedel (1440–1514)

Nuremberg, Germany: Anton Koberger, for Sebald Schreyer and Sebastian Kammermeister, 1493

Brown University Library, Annmary Brown Memorial Collection

Rubricated, with painted capitals at the beginning of the table and text

![Comedia di Danthe Alighieri Poeta Divino: con l’Espositione di Christophoro Landino [Comedy of Dante Alighieri Divine Poet: with the Commentary of Cristoforo Landino]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D12_AEON2318_1S-B1529m.jpg)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Venice, Italy: Jacopo Borgofranco for Lucantonio Giunti, 1529

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

Manuscript on parchment, 14th Century

Brown University Library, Annmary Brown Memorial Collection

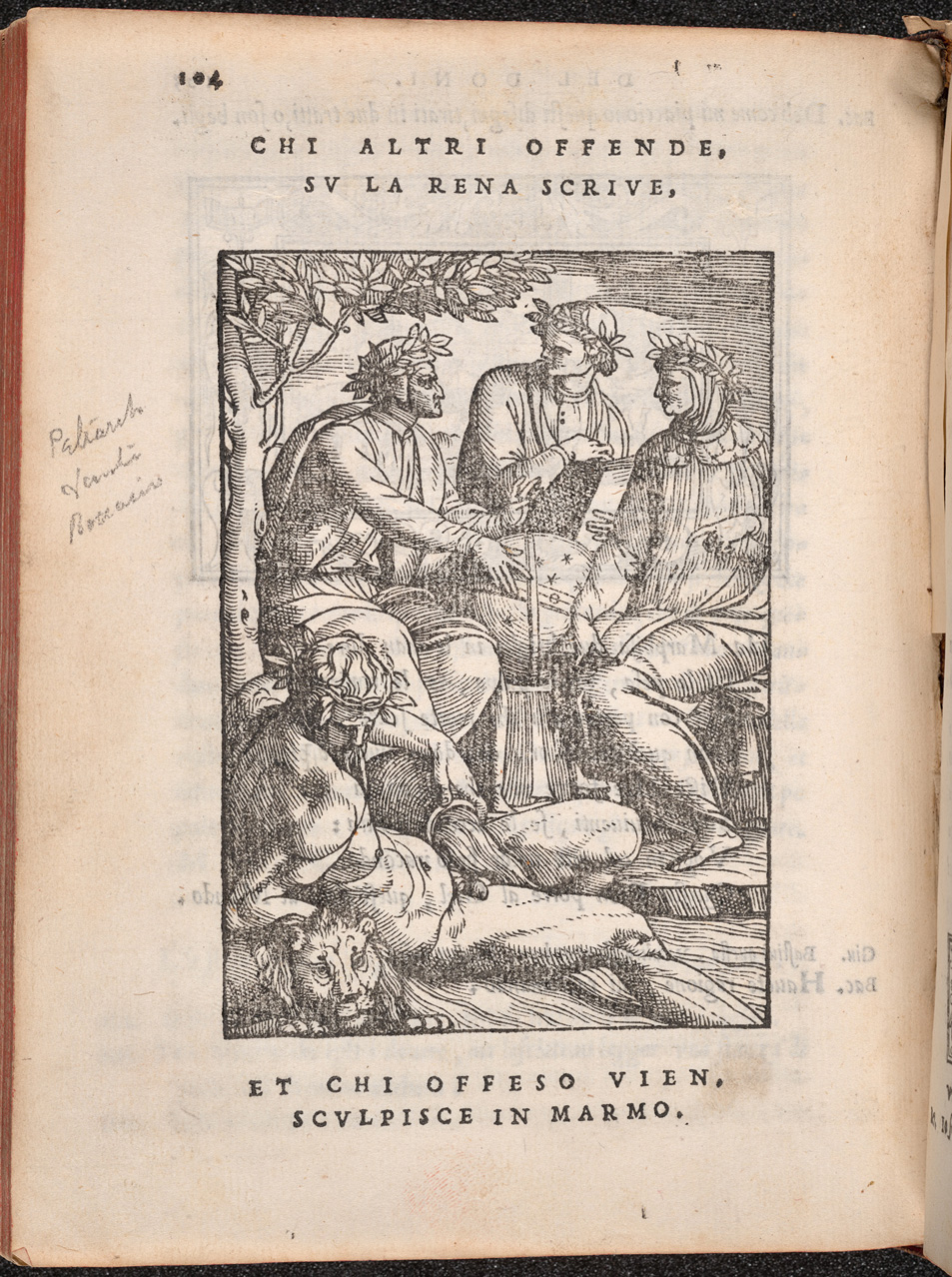

Anton Francesco Doni (1513–1574)

Venice, Italy: Francesco Marcolini, 1552-3

Brown University Library, Hay Star Collection

Woodcut group portrait of Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio

Dante’s Comedy allows readers to experience the three realms of the medieval Catholic otherworld: Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise. Dante’s cosmology was profoundly influenced by Greek and Islamic philosophies that he encountered in translations and commentaries. The structure of the universe featured in the Comedy was fundamentally Aristotelian, with a central Earth surrounded by planets, constellations and fixed stars. The Liber chronicarum (1) shows the order of the heavenly spheres according to this model, but adapted to the Christian theology. From the shores of Purgatory, the stars and signs of the heavens can also be observed through the eyes of Dante and Beatrice, his beloved and guide in Paradise, as seen in the opening illustration of Paradiso in a 1529 edition of the Comedy (2).

Dante’s cosmos views geometry as a way to understand God’s perfection on earth and in the heavens. Illustrations of the Bible further illuminate our understanding of Dante’s universe. Along the left border of this 14th century Antiphonary, a book of liturgical music, the story of creation unfolds (3). The first day, along the left border, portrays God the Geometer. Dante refers to this image in his description of God: “He who revolved the compasses about the limit of the world and within it distinguished so much, both hidden and manifest” (Paradiso 19.40–42). The harmony, symmetry and proportion seen in the world reveal the divinity of God on earth.

The sublime construction of the Comedy makes Dante a divine architect himself: The creator of a cosmos. Dante as an architect, geographer and poet is visually expressed in this 16th century woodcut (4) of the tre corone or three crowns: Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio. In a display of his scientific knowledge and literary status, Dante touches the celestial globe to teach his fellow poets about the principles of the universe. The globe may also refer to the author’s virtuosity in crafting the landscape of the “infernal theatre,” that so inspired Galileo and others to map, measure and illustrate Hell.