Dante and the New World

I turned to the right and considered the other pole, and I saw four stars never seen except by the first people.

—Purgatorio 1.22–4

![Pierfrancesco Giambullari Accademico Fiorentino. Del sito, fórma, & misúre, déllo Inférno di Dante [Pierfrancesco Giambullari Florentine Academic. On the Site, Form and Measurements of the Inferno of Dante] Pierfrancesco Giambullari (1495–1555)](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D20-AEON903m.jpg)

Pierfrancesco Giambullari (1495–1555)

Florence: Neri Dortelata, 1544

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

![Pierfrancesco Giambullari Accademico Fiorentino. Del sito, fórma, & misúre, déllo Inférno di Dante [Pierfrancesco Giambullari Florentine Academic. On the Site, Form and Measurements of the Inferno of Dante]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/AEON903m.jpg)

Pierfrancesco Giambullari (1495–1555)

Florence: Neri Dortelata, 1544

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

Ptolemy (active second century)

Venice, Italy: Giovan Battista Pedrezzano, 1548

Brown University Library, Church Collection

Italian edition of Sebastian Münster’s commentary

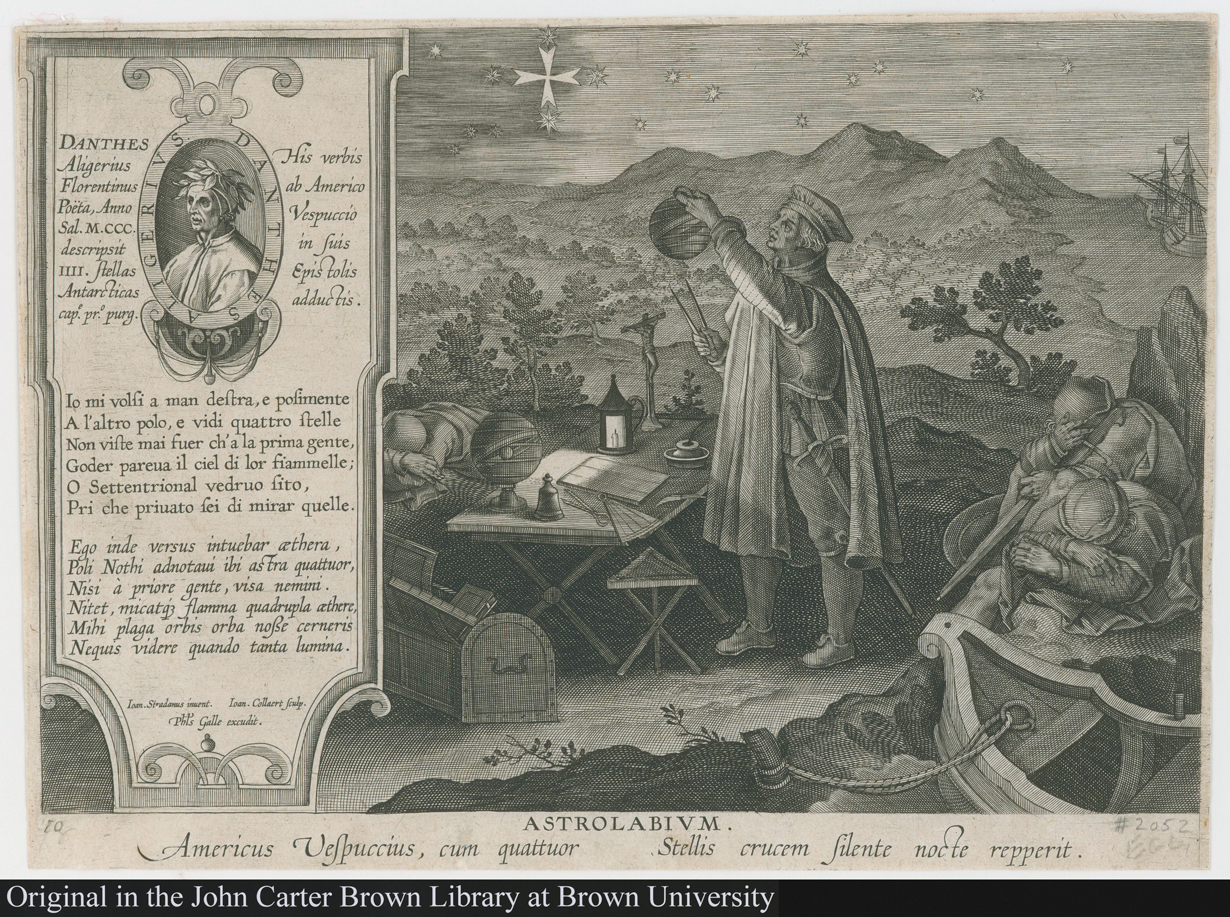

Jan Collaert (1566–1628) after Giovanni Stradano (1566–1628)

Antwerp, Belgium: Philips Galle, c. 1591

John Carter Brown Library

Engraving on paper; part of Nova Reperta [New Inventions of Modern Times]

Abraham Ortelius (1527–1598)

Antwerp, Belgium: Christopher Plantin, 1584

Brown University Library, Lownes Science Collection

Other than key topographical landmarks Jerusalem and Cuma (often considered the entrance to Hell), early maps did not show Hell’s precise location on the globe. Departing from tradition, Florentine academic and linguist Pierfrancesco Giambullari mapped Hell onto the sixteenth-century world in his treatise, “On the Site, Form, and Measurements of Dante’s Inferno” (1, 2). Aerial and global views of two woodcuts situate Hell and Purgatory on opposite ends of the earth, at Jerusalem and its antipodes respectively. Giambullari cited Sebastian Munster’s Geography (3) among his sources in determining Hell’s exact position on the earth. A striking feature of the global cross section is the appearance of the Americas to the left of Hell, labeled as “Terra Incognita.”

Maps of Dante’s poem were not merely didactic or neutral interpretations, but politically-charged visual arguments. Giambullari’s cartographical interpretation of the Comedy should be viewed in light of his relationship to the Medici court. As its linguist, artistic advisor and historian, he clearly hoped to promote Medici political and cultural power. Giambullari dedicated the volume to his patron, Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici, along with “lovers of the Florentine language.” These letters reveal Giambullari’s pro-Florentine attitude, which is emphasized by his use of Tuscan orthography (seen in the accented vowels) he had established under the auspices of the Florentine Academy.

The political implications of Dante’s cartographic authority were also showcased in a print series depicting Amerigo Vespucci’s “discovery” of America (4). Vespucci gazes up at the night sky and gestures toward the Southern Cross, a constellation in the Southern Hemisphere that aided Vespucci on his journey to the Americas. People at the time thought that the “four stars” which Dante describes in Purgatorio were in fact this constellation. Strewn with instruments like an armillary sphere and astrolabe (the title of the print), an illuminated table displays symbols of Vespucci’s knowledge. A vital part of his learning was an intimate familiarity with Dante’s poetry, etched on the left in a cartouche below a medallion portrait of the poet. These verses from the first canto of Purgatorio apparently inspired Vespucci to travel to the New World. By depicting this connection, the artist centrally inscribed Dante, along with Vespucci and Christopher Columbus, in the cartographical history of Italy. This narrative promoted the role of Italians, particularly Florentines, in the conquest and colonization of the Americas. Notably, Dante’s role in the discovery of the New World is absent from geographies created outside of Florence (5).