Envisioning the Heavens: Purgatory and Paradise

To run through better waters the little ship of my wit now hoists its sails, leaving behind it a sea so cruel, and I will sing of that second realm where the human spirit purges itself and becomes worthy to ascend to Heaven…

—Purgatorio 1.1-6; 13-18

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Rome, Italy: Antonio Fulgoni, 1791

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

Engravings based on the 1568 edition of Bernardino Daniello’s commentary

![Lezzioni di m. Pierfrancesco Giambullari, lette nell Academia fiorentina [Lectures of Pierfrancesco Giambullari, Read in the Florentine Academy]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D06_AEON3381-PQ-4390-A2-G5-1551m.jpg)

Pierfrancesco Giambullari (1495–1555)

Florence, Italy: Lorenzo Torrentino, 1551

Brown University Library, History of Science Collection

![De civitate Dei [The City of God]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D35_AEON2765_2S-230m.jpg)

Augustine of Hippo (354–430)

Venice, Italy: Johann and Wendelin of Speier, 1470

Brown University Library, Annmary Brown Memorial Collection

Illuminated white-vine capitals and border; annotations by the Italian humanist Bernardo Bembo (1433–1519)

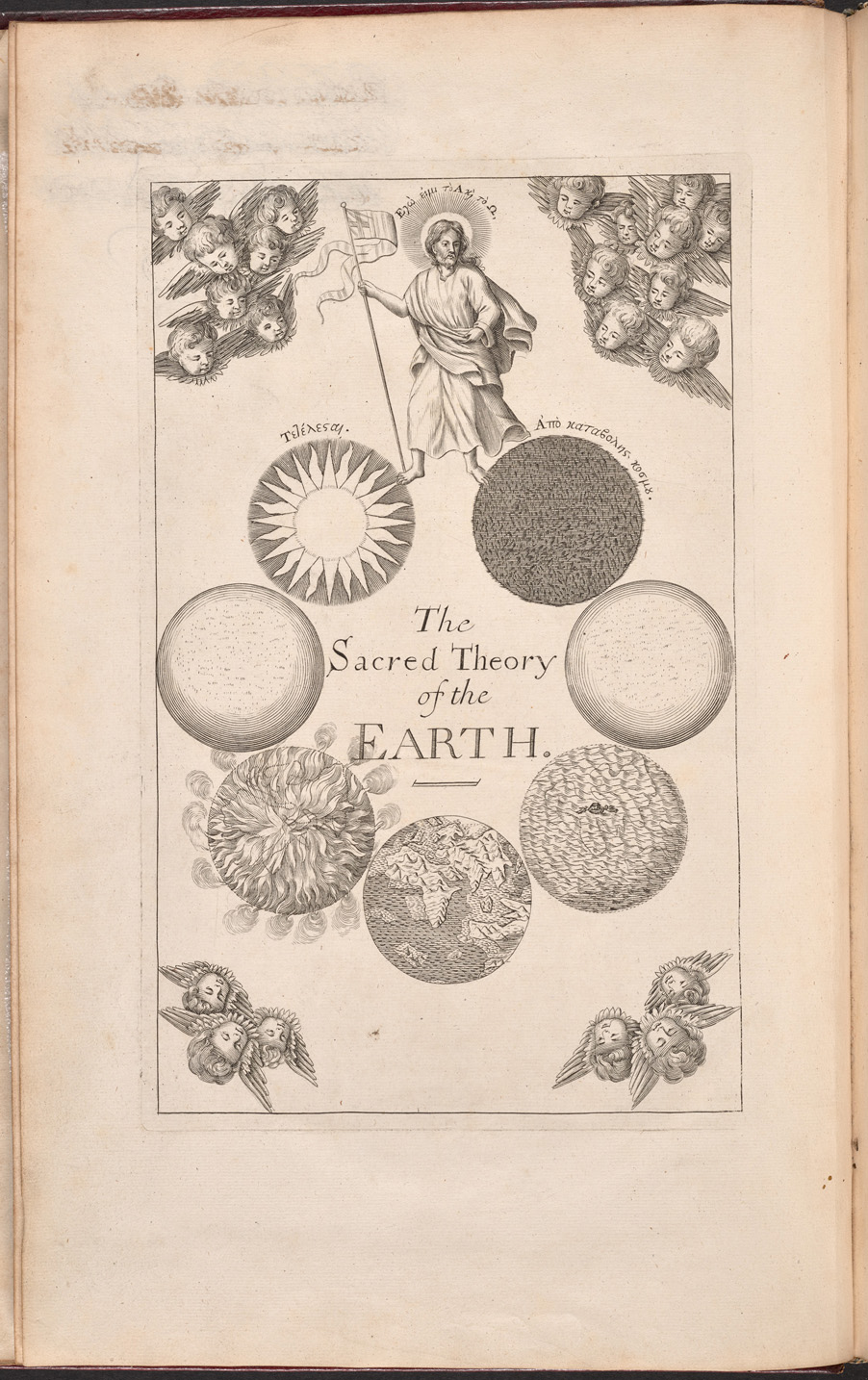

Thomas Burnet (ca. 1635–1715)

London, England: R. Norton for Walter Kettilby, 1684

Brown University Library, Lownes Science Collection

![La visione: Poema di Dante Alighieri diviso in Inferno, Purgatorio, & Paradiso [The Vision: Poem by Dante Alighieri Divided into the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D29_AEON1785_PQ4305-C29m.jpg)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Padua, Italy: Donato Pasquardi and Company, 1629

Brown University Library, Hay Small Collection

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Translated by the Rev. Henry Francis Cary (1772–1844)

Illustrated by M. Gustave Doré (1832–1883)

New York, New York: Cassell and Company, 1883

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Translated by the Rev. Henry Francis Cary (1772–1844)

Illustrated by M. Gustave Doré (1832–1883)

New York, New York: Cassell and Company, 1883

Brown University Library, Chambers Dante Collection

![La divina comedia di Dante Alighieri [The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri]](https://library.brown.edu/create/poetryofscience/wp-content/uploads/sites/63/2018/06/D30_AEON3100_1S-NC242-F57-D35-1802am.jpg)

Dante Alighieri (1265–1321)

Illustrated by John Flaxman (1755–1826)

Engraved by Tommaso Piroli (c. 1752–1824)

Rome, Italy: 1802

Brown University Library, Hay Star Collection

Early Italian edition of Flaxman’s original designs

In Dante’s time, there were few precedents for the description of Purgatory. Using poetic invention and artistic license, Dante portrayed the liminal realm with virtuosic geographical and architectural detail. Located in the Southern Hemisphere, directly opposite Jerusalem, Dante imagines Purgatory as a mountain surrounded by water. The swirling lines of the waves in this illustration of the first canto (1) reflect the turbulence of the “sea so cruel” and the harrowing journey Dante has completed. Sixteenth-century writer Pierfrancesco Giambullari went one step further. He painstakingly measured each level of Purgatory and its location on the earth (2). Spatial interpretations of the landscape of Purgatory provide an interesting contrast to the more metaphysical dimensions of Paradise. Augustine’s City of God (3) was an important source for Dante’s conception of the realm, particularly as it related to the concept of the earthly paradise. Authors such as Thomas Burnet were also interested in the cartography of the heavenly realms (4). Through a series of maps, Burnet charted the geological evolution of the earth prior to the Flood. His theological approach to geography, and particularly the composition of Paradise, resonated with the way Dante mediated Christian doctrine with contemporary scientific thought.

The seventeenth century brought a new title for Dante’s poem, “The Vision” (5). Often dismissed as a fanciful conceit of the Baroque period, the title seems to instead emphasize the theological readings characteristic of the first decades of the seventeenth century. Read as a vision poem, the emphasis on Dante’s theology was also a way to defend him preemptively against the increased scrutiny of the Church, which had criticized the poem for its critical discussion of the papacy. Interestingly, the title was retained in Henry Francis Cary’s English translation (6), which may correspond to the ethereal vision illustrator Gustave Doré gave to the heavenly realms (7). John Flaxman’s linear and minimalistic designs (8) for Paradiso emphasize further the transcendent and ineffable nature of the heavens.