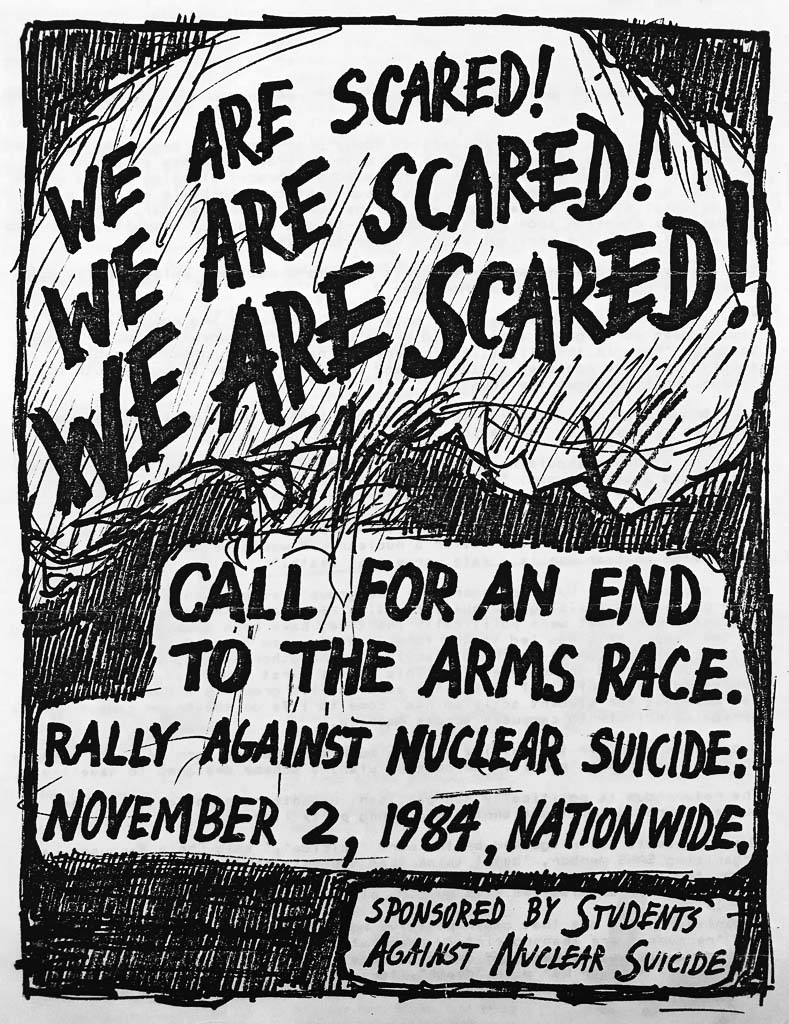

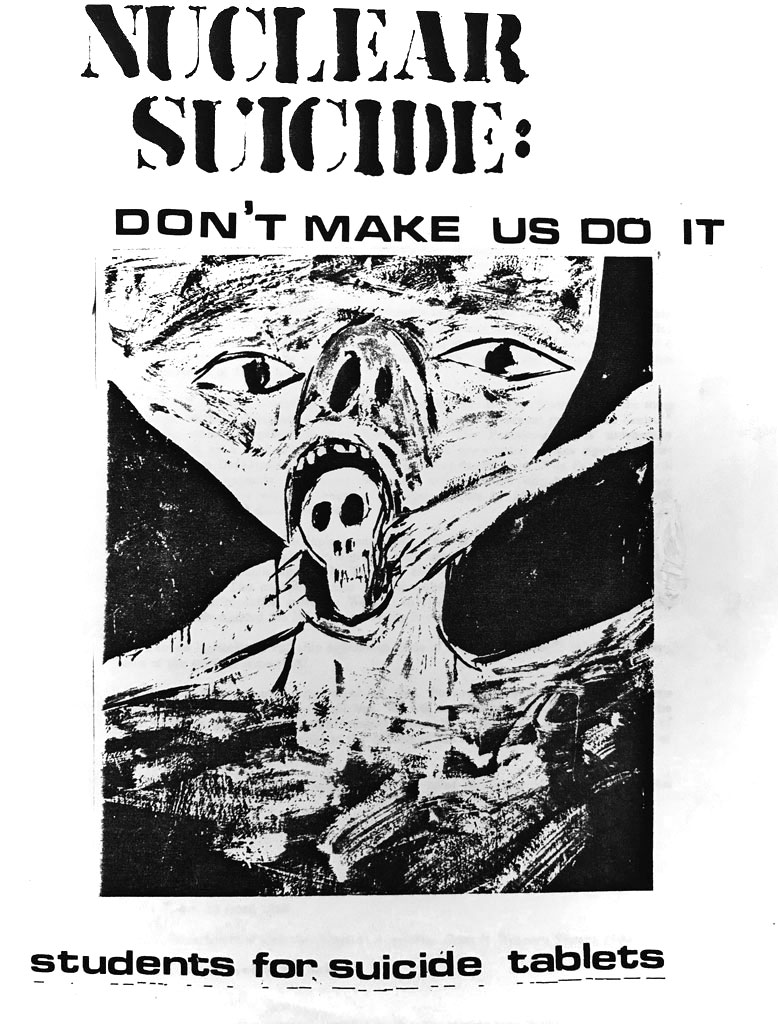

In the fall of 1984, Brown University students held the media’s attention with the passing of a controversial referendum that aroused philosophic and political debates about the severity of nuclear war. During the Undergraduate Council of Students election of October 11 and 12, the referendum, voted upon by 35% of the student body and approved by a vote of 1,044 to 687, called for the University Health Service to stock “suicide pills” which would be made available in the event of a nuclear war. This ethical dilemma was proposed by Jason Salzman ’86 and Chris Ferguson ’87 who intended to start a discourse about nuclear war and suicide. Salzman argued it was important to force people to think about nuclear war in terms of “death” and “destruction” instead of “survival” and “victory.” His argument gained traction with the support of a British doctor who concurred that students should have the choice to choose a “dignified death” rather than be at the mercy of society’s consequences.

Although the “suicide pill” referendum served an important function in symbolically asserting that it is unreasonable to have hope after a nuclear war, Brown still rejected the student’s proposal to stock the pills. Brown’s President at the time, Howard Swearer, wrote a letter to parents to assure them about University’s position on the referendum. Salzman attacked Swearer’s letter to the parents criticizing the administration for not sending a similar letter explaining the university’s position on the referendum to the students.

News of the “suicide pill” referendum at Brown University ricocheted throughout the country, making headlines in national and international papers. However, Salzman believed that his position was “too philosophical” for the press and university administration. Out of curiosity, Salzman interviewed the journalists who interviewed him to understand how the media operates and what made his story so appealing. One journalists explained their interest arose out of the contradiction: “The image of kids committing suicide conjures up a dark image for television.…College students are supposed to be idealistic.” Although the media brought global attention to the referendum, Salzman complained that reporters did not focus on the more significant issue at hand, the inhumanity at stake in our nation’s pursuit of nuclear security.

The seriousness and validity of the “suicide pill” referendum, of course, is debatable. Most students during the time felt that it was a solemn, impressive event, but for many administrators and the outside world, the thought of offering cyanide pills at the university infirmary was a bad joke at best, and utterly outrageous at worst. No matter the opinion, the suicide protests succeeded in uniting activists on campus and bringing more community and national attention to a serious topic. In his unpublished papers, Salzman reflected on the success of the referendum, leaving readers to consider the power of ideas, and to imagine, what would happen if the right ideas were combined.

“It sparked a lot of controversy on campus,” says Salzman. “Most students who were angry were upset about Brown’s image, upset about what the suicide pill thing would do to Brown. Students who didn’t understand were quicker to question the logistics of it: ‘Where are they going to be kept?’ rather than ‘You’re an a-hole.'”

—Brown Daily Herald, 8/28/85