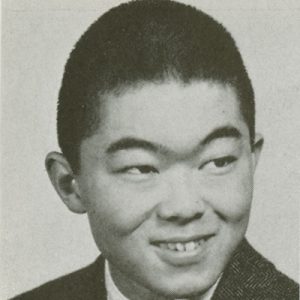

Terry Uyeyama ’58

Terry Uyeyama was born in San Francisco on July 13, 1935 to Japanese immigrant parents. Hi father, a general practitioner before the war, enlisted in the Army shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941. This allowed the Uyeyama family to avoid being placed in one of internment camps that many of their friends and neighbors were sent to. Instead, the family (including sister Toyo, a 1961 Pembroke graduate) followed their father to Camp Grant in Illinois, and then to Fort Harrison, Indiana. Later, when Dr. Uyeyama went overseas, the family moved to Leonia, New Jersey, where Terry would spend many of his formative years.

In high school he was heavily involved in extra-cirricular activities, won honors for wrestling, and ended as a straight-A student with scholarship offers from three colleges. “I selected Brown,” Terry remembers, “but to be honest all of my thoughts after high school were on becoming a pilot.” Uyeyama graduated from Brown in January of 1958, received his commission later that month, and in 30 days was on active duty. This was, of course, the very early days of the Vietnam conflict, and Terry would serve many roles before he ever saw southeast Asia, including fifteen months in the Strategic Air Command and five years as a flight-training instructor. Finally, in October of 1967, he received an assignment in Vietnam.

At that time, pilots were rotated to another assignment outside the combat zone after they had completed 100 missions over North Vietnam. When Uyeyama returned from his ninetieth mission, he got the word: next assignment, Weisbaden, Germany. It was a good assignment. He got out the red crayon, and marked the calendar.

But first there was some celebrating to do for Uyeyama’s navigator, who had just completed his one-hundredth mission and was on his way home. The party lasted well into the night. Among those lifting his glass in good fellowship was Uyeyama’s replacement navigator Tommy, a veteran officer who had already flown 97 missions. Life would change for both of these veteran officers the next day, however, during what should have been a routine flight. “The next day we had an afternoon flight. “Just as we were approaching our target,” Uyeyama remembers, “I felt a jolt on the aircraft.” The men had taken a direct hit right in the navigators cockpit. “Smoke was filling my cockpit, my head was foggy, and I’d lost radio contact with in the back seat….I was having a great deal of difficulty just keeping the plane flying.” Adrenaline rushing, he made the decision to eject.

Pulling the handle of the Martin Baker ejection seat ignites a rocket pack that propels the seats out and allows a 400-foot gain in altitude from the point of ejection. As the seat reaches the apex of its trajectory, a chute is released. Everything is automatic, including separation from the seat. This was especially fortunate in Uyeyama’s case, as he was completely unconscious as he left the burning plane.

“When I came to I was in the water” Uyeyama recalls, “The canopy of the chute had completely submerged below the surface and the currents had wrapped the shroud lines of the chute around my legs, making me incapacitated. I was unable to do anything but move my arms a little bit.” Two of his survival radios were torn away during ejection. Efforts to call for help with the third radio brought no response. He was in the water almost 40 minutes, bleeding constantly, and the danger of a shark attack flashed through his mind. Then he saw some small boats, filled with people chattering very loudly, coming in his direction. “There were about five boats in all, and as the people in them spotted me they started shooting. I took my radio for the last time and made a voice transmission, which remains quite vivid in my memory. ‘They’re going to kill me or capture me,’ I said. “Tell my family I love them, that l’m sorry, and say adios to the guys in the squadron.’”

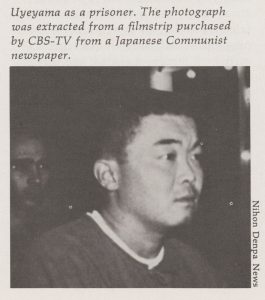

“All these North Vietnamese were local militia and fishermen—but they were heavily armed” he remembers. “The guy in the bow of the middle boat had his AK-47 zeroed in on me as though he was taking aim and getting ready to fire. I looked him squarely in the eye and then, all of a sudden, instead of firing he made a quick, upward gesture with the barrel of his gun. I raised my hands as best I could and moments later I was pulled into the lead boat.” Although he recalls being beaten heavily by his captors, he says shock kept him from being in too much pain. Under the cover of night, he was marching him north, “to what turned out to be five years of hell on earth.”

Because of his injuries, Uyeyama found the trip to Hanoi especially painful. At the various stops, the locals would be brought in to see the captured American. Most would spit or throw rocks. “When we arrived in Hanoi I was blindfolded and kicked out of the truck. My destination was the Hanoi Hilton, a prison where every airman who was shot down in North Vietnam began his career. The prison occupies one huge square block right in the center of the city. Its high walls are covered with glass fragments, topped by electric wires.” Discussing the torture he underwent in an interview for Brown Alumni Monthly in 1973, Uyeyama explains “it’s a continuous process of physical torture in an effort to break you, to try to get you to say something other than name, rank, and serial number. It develops into a battle of wits and a test of physical endurance as you have to see how far you can go, how much pain you can stand, and when it becomes prudent for you to back off and start saying a few things, always trying to circumvent the major issues.” Right from the start, Uyeyama was not a cooperative prisoner. He takes pride in this fact, while admitting that his actions served to bring him verbal abuse, beatings, and solitary confinement in a dark, damp, 8×10 cell.

While alone in his cell, Terry created a daily regimen for himself to keep from “slowly turning into a vegetable.” Along with exercise and light housekeeping, he saved to evening hours for reminicing about his family–his wife Kay, a graduate of Stanford whom he had married in 1960, and three daughters Jody Lee, Wendy Lee, and Sherry Jaye. “I’d daydream about what it would be like to take my wife to a movie once again and just sit there holding hands,” he remembers, “I’d also try to reconstruct the feeling of coming home from work and having the kids jump into my arms, squealing ‘daddy, daddy, daddy.’ But most of all I’d concentrate very hard, trying to keep a vivid picture of my children as I last remembered them. I was afraid that through the months and years ahead, the image I had of them would be completely lost and I would then have nothing left of something that was so precious to me.”

After 14 months, he was transferred out of solitary confinement as was housed with two other officers. He finally had roommates–but this too posed problems. He found himself talking too loud and becoming argumentative over little things that were discussed. And he couldn’t give up his early-morning exercise routine: running in place in a crowded cell at 4 a.m.—the best sleeping time in that sticky climate-—didn’t endear him to his roommates. “I was with a couple of great guys, very gregarious in nature. On the other hand, I’m a man who has periods when I like to be left to myself. I felt that they talked too much and they probably thought I was an absolute ding-dong.”

The “war” ended for Major Uyeyama when he left Olion Airport near Hanoi with the third batch of POWs on January 21, 1973. As the plane left the ground, he didn’t look back. After he made Colonel, Uyeyama served with the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Bergstrom AFB from March 1974 to July 1978, and then served at Lackland AFB until his retirement from the Air Force on June 18, 1980.