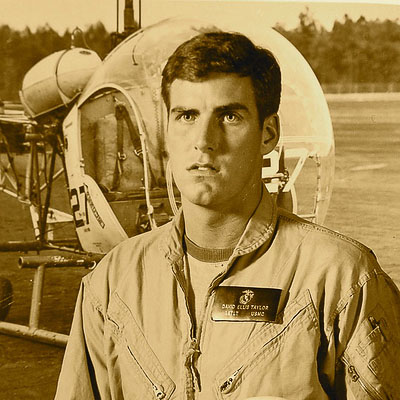

David E. Taylor ’66

(Captain, U.S. Marine Corps, 1966–1971)

Military service was the norm for young men in the early ’60s, but David Taylor’s father, a veteran of World War II, encouraged his sons not to enlist right away. He had served in World War II before college and, regretting the late start on his own education, wanted a different future for David and his older brother. Instead, the Taylor boys headed to college on Navy ROTC scholarships.

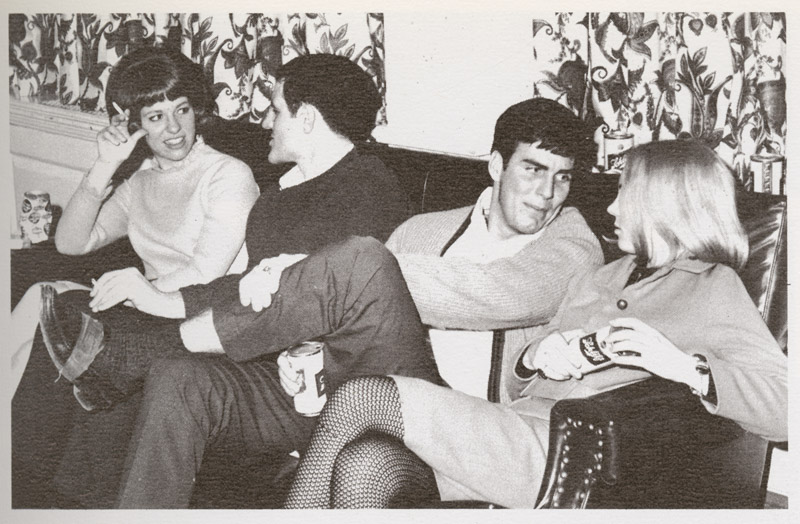

David entered Brown in the fall of, and quickly joined Lambda Chi Alpha fraternity, where his friends were mostly football, basketball, and hockey players.Despite some rocky moments, David finished his four years at Brown strong: he graduated on time, earned a commission, and, at the end of his senior year, met his first wife Kathryn Fuller. After graduating in June of 1966, David joined the Marine Corps—a decision he calls “the manly thing to do.”

With his college days behind him, David traveled to Pensacola, Florida to learn how to fly. He reasoned that the conflict in Vietnam would be over in a year, so the 18 months required for flight school meant he would never have to see war. The training at flight school was intense: the men spent 25 hours in a T-34, took examinations, and endured Dempsey Dumpsters (in which men were dumped into a twelve-foot-deep pool while strapped into a cockpit replica). David was chosen to become a helicopter pilot, flying the CH-53, a “new semi-experimental aircraft that was just wild,” he recalls. After six months of training in the new CH-53, David flew from Portland, Oregon to Da Nang in August of 1968. He describes the descent as something you would see in Dante’s Inferno: “You’re looking out over this landscape, and it’s night and you see nothing but explosions, flares, and fire.” This was the height of the war, right after the Tet Offensive. David and his squadron spent the first night in “hootches”—makeshift huts. The smell was terrible, the bathrooms unsanitary, and the night sleepless. The next day however he relocated to Phu Bai where he would spend the rest of his 13-month tour. Camp here was comfortable: flight officers lived in corrugated Quonset huts equipped with air conditioning. Operating such expensive aircraft demanded a comfortable living environment for proper recuperation after missions. This was a “group of really smart dedicated people. The enlisted guys—different world,” David said.

The mission of his squadron was to support the northern half of operations for the Marine Corps with heavy helicopter support. Since the CH-53 copter could carry 20,000 pounds, sometimes the missions would be to retrieve and deliver a 105-mm howitzer which weighed as much as 7500 pounds. David’s job was to transport it to where the gun installations were. He never knew what he would encounter. “En route, there’s all sorts of crazy things that could happen: there’s artillery going overhead, there’s air strikes occurring, B-52s doing things called Arc-Light or carpet-bombing, and if you ever got in the middle of one of those things, you would wish you hadn’t.” Often David’s copter would bring back the wounded and the dead but according to him, “you didn’t know.”

David and the rest of his squadron made history. In only thirteen months, he flew seven hundred missions and was never shot down. After his tour ended in 1969, David signed up for Helicopter Marine Experimental-1 (HMX-1), whose primary mission is to transport the President of the United States and other high-ranking officials.

Even as the youngest flight officer in the squadron, David was as “highly decorated and had as much combat and flight experience in the CH-53 as virtually any other pilot in the Marine Corps.” But with a year left to serve with HMX-1, David walked away. A second tour in Vietnam after three years back in the states was not an option. Instead, he attended Harvard Business School and later joined the real estate firm Trammell Crow Company. David stayed with Trammel Crow until his retirement, helping it grow from 100 employees with $800 million in assets to 5000 employees with over $30 billion in assets and eventually becoming a partner. Still, Vietnam was the “greatest experience of my life,” David says. “You faced death every day, so you looked at life differently.”