Augustus A. White ’57

(Captain, U.S. Army Medical Corps, 1966–1967)

Augustus A. White III, or Gus for short, grew up as the only child of a middle-class African American family in deeply segregated Memphis, Tennessee. His father had attended the all-Black Mehany Medical College and was a house physician at the local Black hospital, but no amount of prestige could exempt them from the Jim Crow mindset so ingrained in the 1930s south. At the hospital where White’s father worked, even the blood at the blood bank was segregated. As a young boy delivering the black newspaper the Pittsburgh Courier, White occasionally saw front-page photos of the lynchings that were still commonplace. On those days, he has said, “I didn’t want to take the newspaper around. I didn’t even want to handle it.”

When White was eight years old, his father died suddenly, and he and his mother were forced to move from their two¬ bedroom house into the home of an aunt and uncle, who was a pharmacist. White’s college-educated mother got a job as a secretary at a high school, where she eventually became a teacher. White recalls “My father’s death when I was so young meant that most of my relationship with him ended up being my relationship with his reputation,” and the question he heard more often than any other was, “You going to be a doctor like your dad? Your dad was a fine man, a great doctor.”

Education was always important to Gus’ family and at 13 he left Memphis for the Mount Hermon School for Boys, an exclusive New England prep school (now Northfield Mount Hermon). Students earned tuition money by waiting tables and sweeping floors. Although he suffered from culture shock at this tiny northwestern Massachusetts enclave, he thrived at Mt. Hermon, singing in the choir, excelling academically, and earning varsity letters in football, wrestling, and lacrosse.

In 1953 White opted for college at Brown. “Brown had good athletics, highly regarded pre-med studies, and, my grapevine informed me, they not only took Negroes, they treated them well,” he recalls. “Four or five each year. Never more, but never fewer, either.” At Brown, White worked grueling hours in order to play football–he was a varsity offensive and defensive end–while simultaneously earning high grades in his premed studies. In 1957 he received the Class of 1911 Award, given to the senior with the highest scholastic standing for the first seven semesters at Brown University. Like many young men at Brown he also joined a fraternity, Delta Upsilon, where he became the first African American fraternity brother at the University.

White went on to medical school at Stanford, followed by an internship at the University of Michigan Medical Center and an orthopedic residency at Yale. As his residency drew to a close, however, he received word from his draft board back in Memphis. It was 1966, just as the Vietnam War was escalating, and he’d be drafted in a few months. As the only son of a widowed mother, the thirty-year-old White faced a sobering decision. He could probably avoid going to war if he volunteered for the air force, the reserves, the national guard, or the public health service. But after a long internal debate, he chose the most dangerous option: joining the U.S. Army Medical Corps. For an orthopedic surgeon, it was a ticket to Vietnam.

White came up with various reasons for going. He felt a debt to those who had fought to defeat the Nazi regime in World War II. He also reasoned that in the medical corps he would be saving lives, and after nine years of studying and training, he looked forward to using his surgical skills intensively. “There would be no place in the world where there would be a better opportunity or a greater need” he reasoned.

White arrived in Vietnam in August 1966. He was stationed at the 85th Evacuation Hospital at Qui Nhon, on the coast 250 miles northeast of Saigon. When casualties rose, the camouflaged helicopters arrived again and again, and White and his colleagues might work thirty-six or even forty-eight hours straight. “It was like sitting beside a river of blood,” White wrote in a diary he kept during his year in Vietnam. A Quonset hut with a corrugated metal roof served as the triage building. Corpsmen who met the helicopters would rush in carrying stretchers, setting each one down on a pair of sawhorses. In the chaos, White says, “your hands to some degree get on automatic pilot.”

White noticed that a disproportionate number of the wounded were black-like him. Although African-Americans composed 11 percent of the U.S. population in the mid-sixties, roughly 20 percent of Americans dying in combat were black. White wrote in his diary: “The brothers have informed me of the inordinate frequency with which they were chosen as ‘point men.”’ (The defense department would eventually correct the imbalance.) Even at the hospital in Qui Nhon, White says, “There was a lot of resentment from white males having a surgical peer who was black.”

Of the thirty physicians at Qui Nhon, White was one of two African Americans. He considered beforehand how he would present himself. White decided to heed an aphorism he’d heard: “If there’s no music, you don’t shuffle.” He would be direct with instructions or corrections-not arrogant, but not apologetic, either. Several months into his tour, six of White’s colleagues went to complain about White to their commanding officer, Major John A Feagin Jr., also a surgeon. Feagin still remembers what they said: we don’t like Gus White dating our white nurses. “I said I thought the armed forces had integrated in 1945,” Feagin recalls answering. “I was disdainful.”

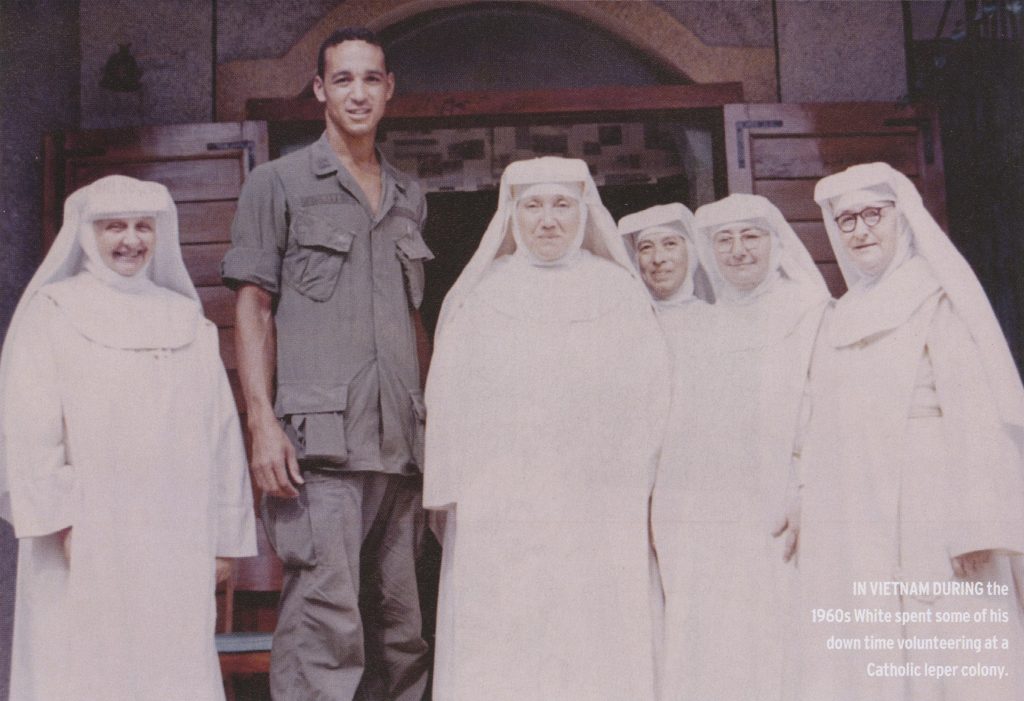

White got a break from the turmoil most Saturdays. He and Feagin and a nurse would visit the St. Francis leprosarium, seven miles from the hospital. Catholic nuns from Europe and Vietnam ran the community of 1,500 men, women, and children. The nuns wore ankle-length white habits and lived in a tranquil beachfront village built of pastel-colored marble found on the site. “It was a wonderful thing,” White recalls, “to leave all that blood and gore and stink and destruction in the town and to drive over the hill and enter this marble-laden community that looked like the set of a Walt Disney movie.” The colony was a strange reprieve from the stresses of war. “We helped soldiers, certainly,” he remembers, but “this was somehow more peaceful, more gratifying, less frustrating. It’s better to fight natural disease than man-made trauma.” White also treated Viet Cong hurt in battle and brought in by the American medics both as a humanitarian gesture and because prisoners might serve as pawns. Enemy fighters got the same treatment as Americans and South Vietnamese.

After serving his year in Vietnam and another year in the army in California, White spent eighteen months earning a PhD in orthopedic biomechanics at the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. It was there he met his wife, Anita, a Swede, and it was also there, he realizes in retrospect, that he made a formal commitment to promoting diversity in medicine. In Sweden, he says, race was simply not an issue. He also began work that provided the foundation for his book, The Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, which established White as a leader in his field. He worked and taught at Yale for nine years, then joined the Harvard faculty in 1978. He collected a list of honors that takes up two pages of his C.V., among them the Bronze Star for his service in Vietnam, six years as a Brown trustee, and the Diversity Award of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons.

Since retiring from the operating room in 2001, White continues his pursuit of social justice in medicine. His 2011 book Seeing Patients: Unconscious Bias in Health Care, is a combination memoir of and manifesto that lays bare the troubling and insidious ways that prejudice gets in the way of good medicine. He is now writing an autobiography, in part about his year in Vietnam. Because of his experience, he says, “when I meet any kind of veteran, I say thank you-the same way I thank schoolteachers.” As for policymakers, White says, “Every leader should spend a day with a military surgeon or a nurse–a day in a military hospital. You wouldn’t have to say a word to them.”