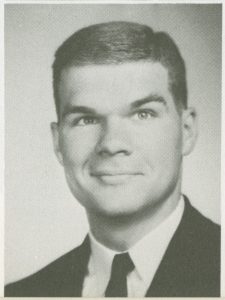

Jerry A. Zimmer ’66

(Captain, U.S. Marine Corps, 1966–1969. Missing in action, August 29, 1969, Da Nang, Vietnam)

The oldest of three brothers, Jerry Zimmer was born and raised on a dairy farm in the tiny town of Maine, New York. The five Zimmers were a close-knit family, sharing chores and meals and attending the local Congregational Church together each Sunday. Of his three brothers, Jerry’s widow Elaine Zimmer Davis says he was regarded as the most studious and religious. “Jerry was sort of revered within his family. And within the town,” recalls Elaine.

Growing up on the farm taught Jerry about hard work from a young age: his mornings would begin around 4:00 am, when he would rise to milk the cows and deliver his paper route before the first school bell. At Vestal High School, Jerry was a member of the National Honors Society and star player on the football team; his coach, a former marine, was his mentor. A scholarship from the Naval ROTC made possible Jerry’s dream of a first-rate education at Brown, which he attended after turning down an offer from the Naval Academy. For the son of small-town dairy farmers, an elite school like Brown represented hope, opportunity, and the future.

Jerry’s quiet confidence likely helped ease his transition from the farmlands of upstate New York to Brown University’s bustling campus, where he arrived in the fall of 1962. Besides his weekly NROTC commitments, Jerry took a job parking cars, played on the freshman football team, and pledged Delta Tau Delta. Elaine recalls that Jerry was a true “guy’s guy” and had a knack for making “people feel like they were valuable no matter what.”

Jerry retained a strong sense of faith throughout his time at Brown and later, in Vietnam. In 1963, his days already packed with commitments, Jerry added another—Elaine. By the end of Jerry’s junior year, when Elaine was graduating from Bryant with her two-year Associates Degree, the couple knew they wanted to marry. Back in Maine, NY that Thanksgiving of 1965, Jerry proposed to Elaine at the table in front of his entire family. On June 11, 1966, Jerry and Elaine were married.

After a frugal honeymoon in the Bahamas, Jerry moved from the NROTC to the Marines, and he and Elaine reported to basic training at the Officer Candidate School in Quantico, Virginia. There, the couple lived in a small apartment with other officers and wives in Triangle Woodbridge, Virginia, about 20 miles from the base; their neighbors were Carol and Charlie Piggott, classes of Pembroke ’66 and Brown ’66, respectively.

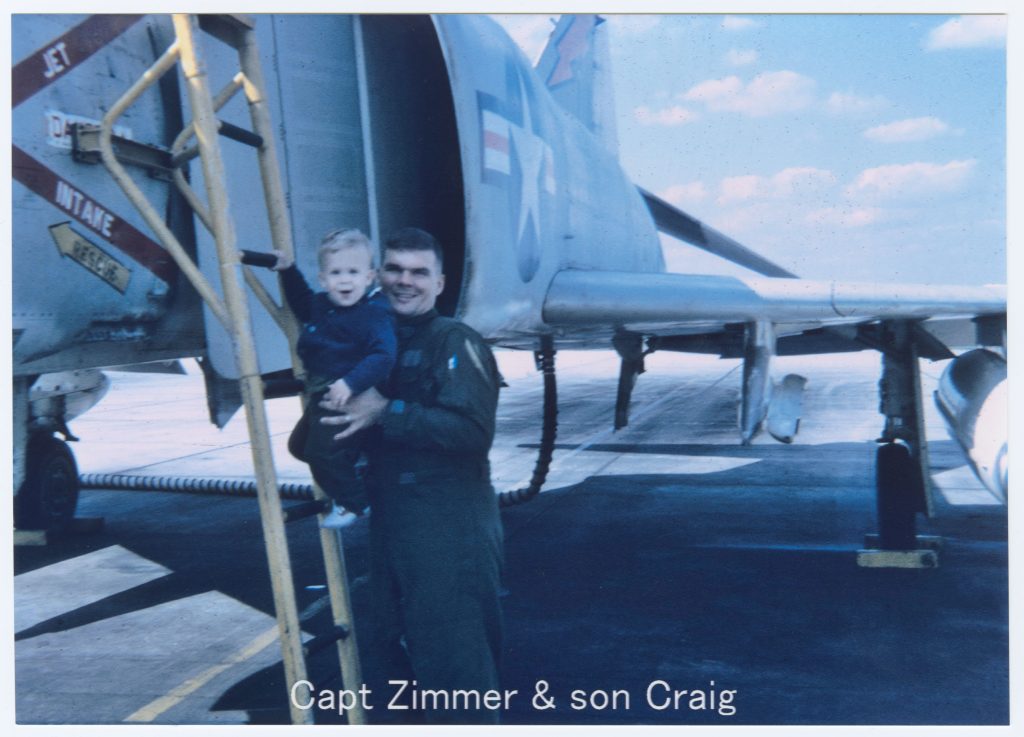

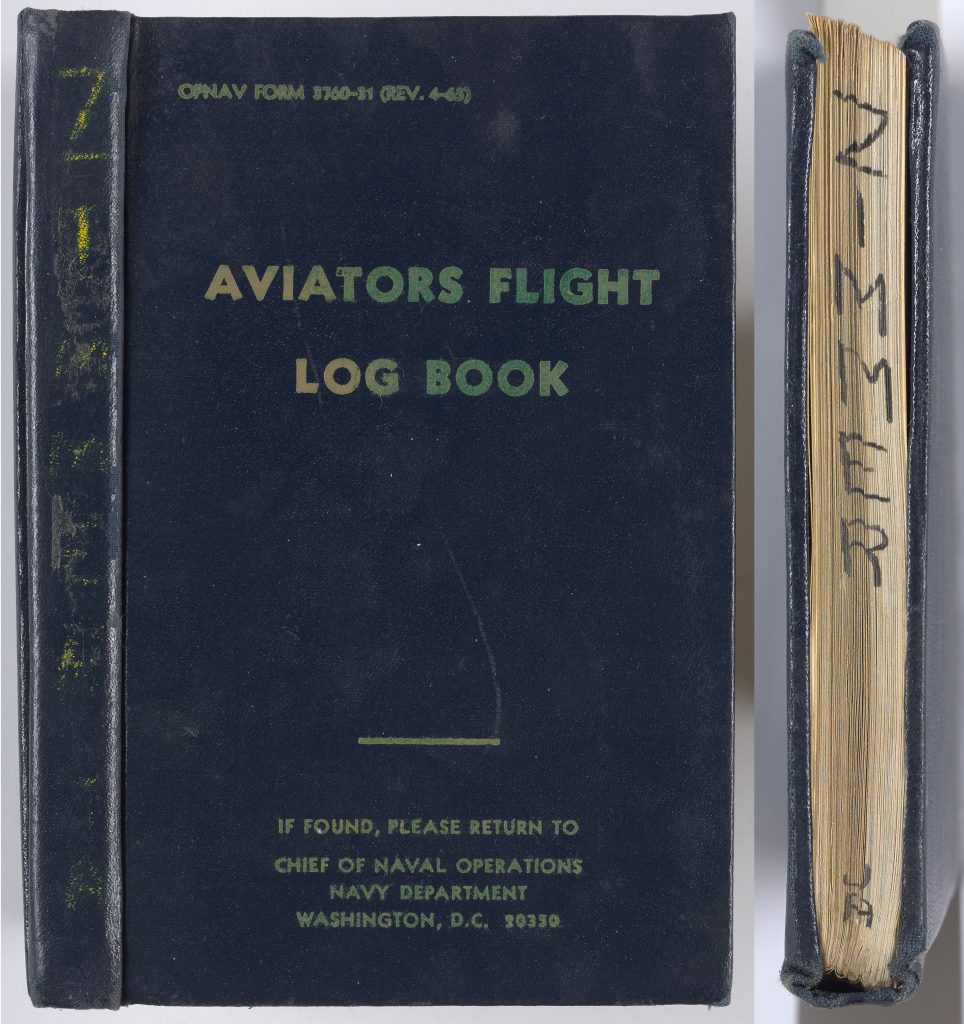

Jerry knew he wanted to become a jet pilot—he’d already gotten his private pilot’s license while at Brown, through a government program. Two weeks after basic, he and Elaine headed down to flight school in Pensacola, Florida. Jerry was a natural leader, hosting regular study groups for those who, like him, wanted to fly jets. Indeed, after graduating at the top of his class, Jerry receive a coveted jet assignment-one which came with extensive relocating for advanced training. The couple moved from Florida to Mississippi, back to Florida, to Texas, to Cherry Point, North Carolina, and then finally to Beaufort, South Carolina. In Beaufort, Jerry’s last training station before leaving for combat, he completed his pilot training to fly the F-4 Phantom. “That was a two-man aircraft. The backseat was a navigator who had no control [the], over the aircraft, but he could eject separately from the pilot if necessary. And that’s what Jerry wanted. And it was the toughest to get,” Elaine says. Jerry got it. Along the way Elaine had given birth, their son Craig.

After Beaufort, Jerry and Elaine bought a house through the VA in Smithfield, Massachusetts, close to Elaine’s parents. “He had about a week or two in the house, and then he left for Vietnam. I took him to Boston, and that was the last time I ever saw him,” Elaine recalls. This was March of 1969.

For Jerry, like. many others, the reality of the war came as some what of a surprise. “I am certain that the first letter I got from him was the saddest letter” Elaine recalls. “I think he was shocked at what he’d gotten himself into. In the sense that he wasn’t frightened, but I think he never pictured Vietnam and the lifestyle. I don’t think Jerry had really thought about that enough… Going to Vietnam was not, I know we saw pictures, but when you’re in the air…it’s like a movie. You know, you’re not, you know, you’re not there. You’re really not seeing the enemy’s eye up close.”

In Vietnam Jerry was part of the VMFA-542 (Marine Fighter Attack Squadron) stationed in Da Nang. Even as a section leader, there was never enough flying for him. As a jet pilot, Jerry chiefly flew close air support missions, “supporting the ground troops,” Elaine recounts. Mostly, Jerry would drop bombs to clear landing zones so helicopters could drop off and pick up ground troops. He also began taking graduate school classes in Business Law at the University of Maryland’s extension in Da Nang

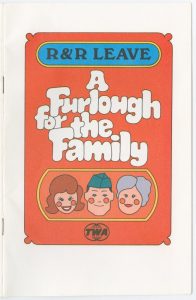

After six months in-country, Jerry was eligible for R&R leave, and as Elaine recalls he started talking about their rendezvous almost immediately. “That was the side of Vietnam that said, ‘If I can make it to R&R, we’ll be okay.’ So I had these brochures that were the most ridiculously funny things. It looked like Ozzie and Harriet, I swear to god, on the cover.”

Jerry and Elaine had made plans to travel to Hawaii together. However on August 29, 1969, Everything changed. that morning in Da Nang, Jerry and his Radio Intercept Officer (RIO, or navigator), Al Graff, were waiting to fly. “I think it was like noontime or something, he was sitting out there, and I’m sure he was bored…Jerry always was bored if he wasn’t flying,” Elaine recalls. Finally a call came in: a reconnaissance team was going into an area considered a hotbed. Jerry and his section needed to drop bombs to clear the area for ground troops and a helicopter to land. As Jerry was pulling up after dropping his first load, he was caught in 50-caliber gunfire. Taking down an F-4 with gunfire is a huge coup; the jets travel upwards of 500 miles per hour, and being felled by groundfire was rare. It is unclear what exactly caused Jerry’s plane to crash that day. One possibility is that his hydraulics went out, making it impossible to pull up to a safe altitude. Another, more likely outcome, Elaine explains, “is that the aircraft, it was a very mountainous area where they needed to come in and then get right up, and that he was hit. And they would’ve died if they tried to eject because they didn’t have the altitude.”

A few days later in Smithfield, Elaine had packed Craig’s suitcase and was waiting for Jerry’s parents to come pick him up in preparation for her R&R trip with Jerry. “That day I was sitting in our house. The green car drove up, and this sweet, sweet captain-Captain Dejulay…. I invited him in. I knew…I don’t know how I knew, whether it was from television segments, but Craig was holding onto my leg,” Elaine recalls. “When I bought the tickets he was dead already…We were due within a week to meet each other. I mean, I was really literally on my way to R&R, and women sometimes got to Hawaii and found out that their husbands were dead. And so in some ways, I’m very lucky that that didn’t happen.” She remains “incredibly sad that we didn’t have R&R together. I never forgave God for that.” Soon after, on September 4, 1969, Elaine received a Western Union telegram informing her of Jerry’s death: he was “19 ½ miles south of Da Nang, Quang Nam Province, Republic of Vietnam. He was the pilot aboard an F4B aircraft conducting an airstrike in support of a reconnaissance insert in a known high threat area. His plane was observed to impact with the ground after an ordinance delivery. Due to the nature of the incident his remains were not recovered.”

Elaine decided to join her friend Carol Piggott, whose husband Charlie had been killed three months earlier, near a military base in California. “I wanted to be near people who understood. I didn’t want to be around people who thought my husband was a killer.” By Thanksgiving they were in California. Once they were settled, Elaine, Carol, and their friends would “go where the military hung out, and you would have thought we were the happiest people,” she says. “We didn’t want to scare people away. There is something that I learned early on. When guys or couples had been through Vietnam and they were coming home, people in our position, my position, wanted to be near them. But by the same token, they couldn’t deal with our loss.”

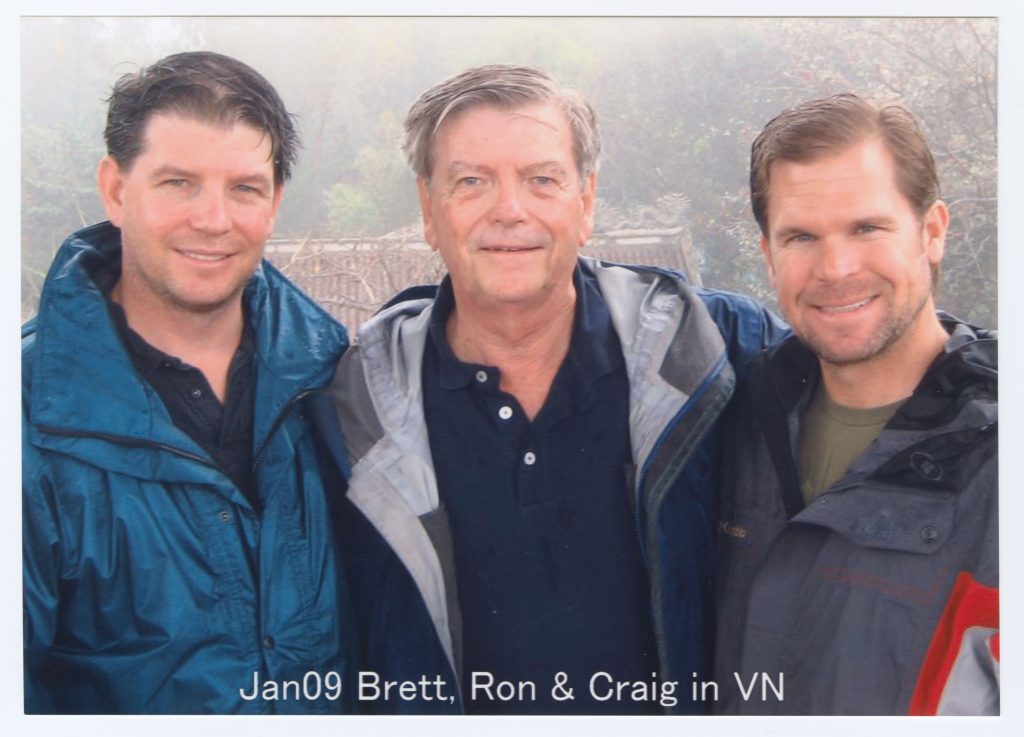

Soon after moving to California Elaine met Ron Davis, who had returned from 13 months as a helicopter pilot in Vietnam the same day Jerry was killed. He lived across the street; eventually the two were married. She graduated from journalism school and worked internationally as a travel writer for a time before travelling to Vietnam in 2006 with Ron. The two went to look for Jerry’s crash site and remains in Da Nang with no luck. Then in January 2008, Ron, their son Brett, and Craig travelled again to Vietnam to try again. Elaine says: “We learned pretty quickly that the government had made some mistakes. The coordinates we received in 1995 gave Craig sort of the closure, all of his dad’s records that the government put his dad’s case in. There was a group called JPAC, Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command. They sent Craig Jerry’s jacket and put his case in the “no further pursuit” category. In 1992 or 1993, the government resumed relations with Vietnam and at that time our government went in and re-evaluated all the cases that were still outstanding… The coordinates given were two klicks off; one klick is a kilometer.” In other words, the government had conducted its investigation of Jerry’s case using the wrong coordinates; if there were crash debris or remains to be found, they had yet to be discovered. But JPAC refused to OK the men’s search; reopening Jerry’s case would be too expensive.

In March 2009, Elaine returned herself with Gene Mares, who had flown with Jerry in country while in VMFA-542 and served as best man at their wedding. This time the search was successful: they recovered debris from the crash along with “life support”—pieces of Jerry’s flight suit and parachute. In September 2009, a memorial service was held for Jerry at Arlington Cemetery. JPAC has since reopened Jerry’s case; in August 2010, they began excavating his crash site.

Elaine continues to work closely with JPAC; and chronicles her search for Jerry.