Avoiding Moiré

Because we photograph a great deal of prints and engravings, moiré patterning is an issue that we must consistently keep an eye out for. Moiré patterning often occurs during image capture; it can also happen if you’re viewing an image at a certain magnification, but this is easily addressed by changing the magnification. It’s when moiré patterning enters during image capture that you must address it immediately, since it’s difficult to remove without creating more image artifacts.

Moiré patterning happens when your subject has some type of regular pattern – in our case, this is usually regular lines in an engraving, but can also happen when photographing textures on paper or cloth that have a regular weave to them. When the regular pattern of the subject overlaps with the regular pattern of the image sensor, the moiré patterning is born. It’s usually seen as bands of color, or light and dark.

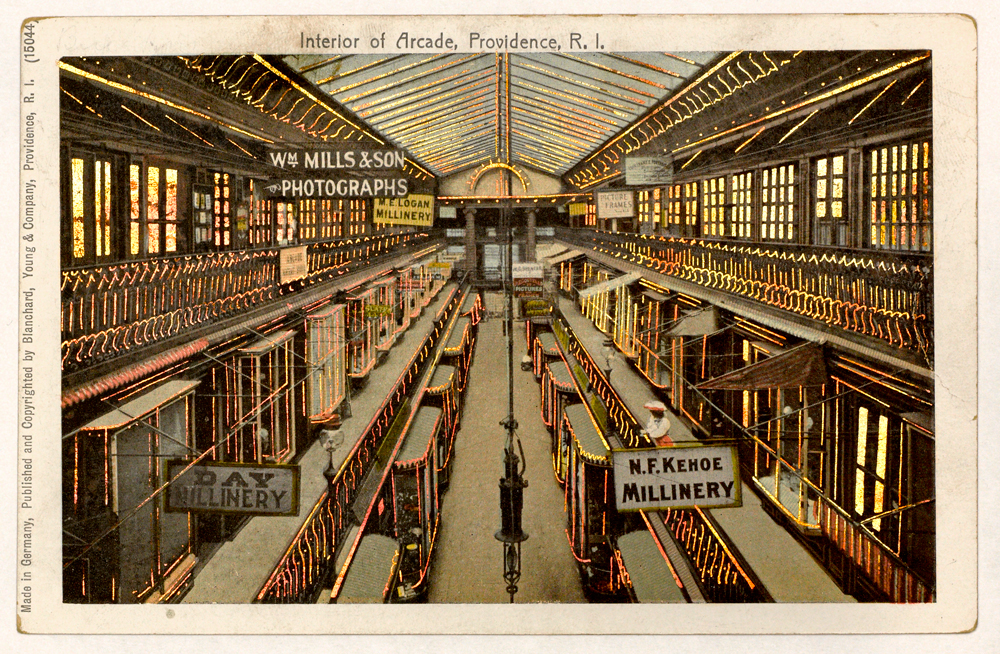

The two images above are examples of both kinds of moiré patterning. The image on the left, with the black-and-white pattern, happened due to image magnification. This image itself was fine, but viewing it at this magnification was problematic. The image on the right, however, shows moiré patterning that happened during the capture process. You can clearly see the bands of color that, rather than being a function of viewing the image, are actually present in the image itself.

Correcting the viewing problem is a non-issue; one must simply view the image on a different monitor or at a different magnification. Correcting the patterning that happens during capture is actually almost as simple: it’s all about the orientation of the original. Because moiré patterning is a function of the relationship between overlapping patterns, all we have to do to correct this is change that relationship; put another way, we have to change the alignment of the patterns. For this object (from our Rider Broadsides collection), I had been photographing all objects in the collection aligned as relatively straight verticals to the sensor. To correct the alignment, I simply tilted the image so it was crooked in the capture (it’s important that this isn’t a 90˚ tilt, but a more arbitrary tilt). This corrected the problem immediately. Below is the final image, as well as a detail of the most problematic area of the object.