About the Exhibit

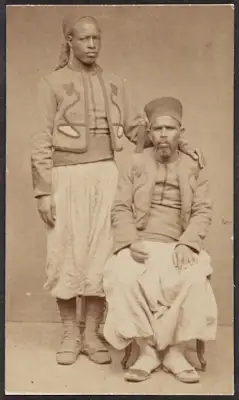

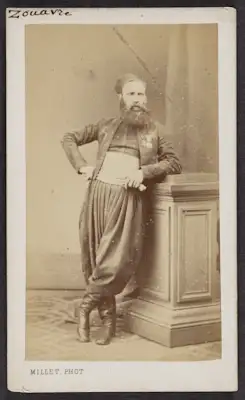

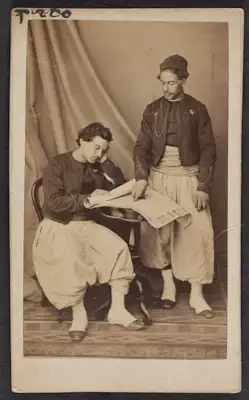

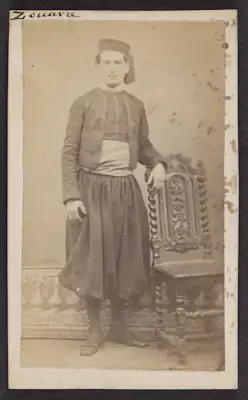

Americans have adapted uniforms into costumes since the masquerade balls of colonial days to today’s historical films and battle reenactments. The practice took an unexpected form in the first decades following the American Revolution when the early presses of the United States closely covered imperial insurrections that unfolded across Islamicate societies against the three towering empires of the era: the Greek War of Independence against the Ottomans (1821–29), the Ottoman Algerian resistance to the French (1830–48), and the Indian uprising against the British (1857). Alongside depictions of these struggles, American popular media paid careful attention to the “national” dress and military uniforms that could potentially unify a revolution or even aid in controlling insurrection. As the young nation navigated its connections to the Islamicate world, some reinterpreted visual and sartorial modes of imperial resistance. The reverberations of these events led to the emergence of orientalist costumes and dress that transformed regional revolutionary garb into American fashion statements of solidarity, fascination, and emulation.

Through these forms of cosmopolitan materialism, Americans announced their political stances on historic movements, sometimes also asserting their country’s imperial ambitions and legacies as it solidified its standing in the world. Such sartorial translations from uniforms to fashion informed America’s evolving relationship with its own revolutionary past. Each medium these costumes inhabited aided Americans in creatively redefining their country’s transforming identity on the international stage while facing resonant issues in their new nation, including foreign trade, slavery, and humanitarianism. Alongside contextualizing documents, the works here vividly illustrate how the U.S. wielded these movements of imperial insurrection to remold its own world image and don it with aplomb.