Studio on the go

July 8, 2013 by lelgin | Comments Off on Studio on the go

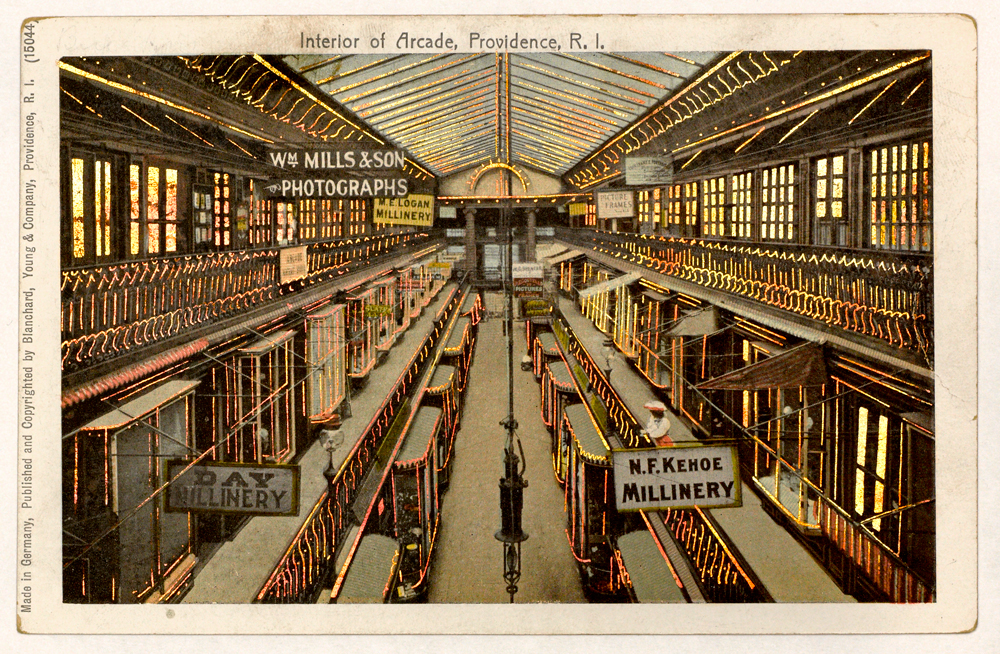

The library Annex: known for housing a vast collection of books not stored in our on-campus libraries, it’s also home to an art vault for Brown’s portrait collection.

During the slower summer months, DPS has the time to turn its attention towards important projects that may not be as time-sensitive as work done during the academic year, but remain a vital part of the work of digitizing the collections of both the University Library and the larger institution. Many of these projects involve on-site work, where my colleague Ben and I travel to locations on and off campus to photograph rare and oversize objects.

One undertaking this summer has been work for University Curator and Senior Lecturer Robert Emlen, who has identified a number of paintings that require photography. Many of the works have been conserved, some have not been previously digitized, and several had been captured with older (c. 2003) digital technology.

Some of these paintings are part of the Rush C. Hawkins Collection, housed in the Annmary Brown Memorial. The majority of the works are from the Brown Portrait Collection, made up of paintings located all across the Brown campus. There are also a number of paintings stored at the library Annex, home to many volumes not currently stored on campus.

In order to capture these works as best as possible, we have a traveling setup that we bring with us. This includes our digital back, mounted on a medium format SLR, tripod, hot-shoe level, x-rite color checker card, tungsten light set with light stands and umbrellas, and a MacBook Pro with Capture One installed for tethered shooting. We also bring white foam core reflectors to even out lighting, and black foam core to reduce any unwanted light (which gives a nasty glare off oil paint). Below is a setup from a shoot in the Annex, where you can see most of this equipment brought into play.

Testing this shot with the color checker card and hot shoe level. We’re purposely photographing the painting on its side to make the most of the camera’s 80MP sensor (without having to rotate the camera) as well as to ensure as even light spread across the painting as possible.

The painting we are photographing above is a portrait of Barnaby Keeney, the 12th president of the university. This is the final product:

Keeney, Barnaby Conrad (1914-1980); Artist: Feldman, Walter; Portrait Date: 1961; Medium: oil on canvas; Brown Portrait Number: 201

The portrait was painted in 1961 by Walter Feldman (himself a Brown institution, now Professor Emeritus of Art); an interview with Professor Feldman for a celebration of BREATHTAKEN, a new collaborative publication released in 2012, can be found here.